Last time, I described how to write a simple Android app and get it talking to your code on Linux. So, of course, we need an example. Since I’ve been on something of a macropad kick lately, I decided to write a toolkit for building your own macropad using App Inventor and any sort of Linux tools you like.

I mentioned there is a server. I wrote some very basic code to exchange data with the Android device on the Linux side. The protocol is simple:

- All messages to the ordinary Linux start with >

- All messages to the Android device start with <

- All messages end with a carriage return

Security

You can build the server so that it can execute arbitrary commands. Since some people will doubtlessly be upset about that, the server can also have a restrictive set of numbered commands. You can also allow those commands to take arguments or disallow them, but you have to rebuild the server with your options set.

There is a handshake at the start of communications where Android sends “>.” and the server responds “<.” to allow synchronization and any resetting to occur. Sending “>#x” runs a numbered command (where x is an integer) which could have arguments like “>#20~/todo.txt” for example, or, with no arguments, “>#20” if you just want to run the command.

If the server allows it, you can also just send an entire command line using “>>” as in: “>>vi ~/todo.txt” to start a vi session.

Backtalk

There are times when you want the server to send you some data, like audio mute status or the current CPU temperature. You can do that using only numbered commands, but you use “>?” instead of “>#” to send the data. The server will reply with “<!” followed by the first line of text that the command outputs.

To define the numbered commands, you create a commands.txt file that has a simple format. You can also set a maximum number, and anything over that just makes a call to the server that you can intercept and handle with your own custom C code. So, using the lower-numbered commands, you can do everything you want with bash, Python, or a separate C program, even. Using the higher numbers, you can add more efficient commands directly into the server, which, if you don’t mind writing in C, is more efficient than calling external programs.

If you don’t want to write programs, things like xdotool, wmctrl, and dbus-send (or qdbus) can do much of what you want a macropad to do. You can either plug them into the commands file or launch shell scripts. You’ll see more about that in the example code.

Now all that’s left is to create the App Inventor interface.

A Not So Simple Sample

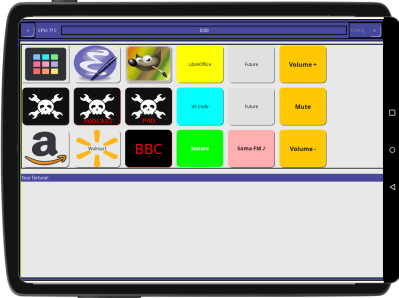

App Inventor is made to create simple apps. This one turned out not to be so simple for a few reasons. The idea was that the macro pad should have a configuration dialog and any number of screens where you could put buttons, sliders, or anything else to interact with the server.

The first issue was definitely a quirk of using App Inventor. It allows you to have multiple screens, and your program can move from screen to screen. The problem is, when you change screens, everything changes. So if we used multiple screens, you’d have to have copies of the Bluetooth client, timers, and anything else that was “global,” like toolbar buttons and their code.

That didn’t seem like a good idea. Instead, I built a simple system with a single screen featuring a toolbar and an area for table layouts. Initially, all but one of the layouts are hidden. As you navigate through the screens, the layout that is active hides, and the new one appears.

Sounds good, but in practice there is a horrible problem. When the layouts become visible, they don’t always recalculate their sizes properly, and there’s no clean way to force a repeat of the layout. This led to quirks when moving between pages. For example, some buttons would have text that is off-center even though it looked fine in the editor.

Another problem is editing a specific page. There is a button in the designer to show hidden things. But when you have lots of hidden things, that’s not very useful. In practice, I just hide the default layout, unhide the one I want to work on, and then try to remember to put things back before I finish. If you forget, the code defensively hides everything but the active page on startup.

Just Browsing

I also included some web browser pages (so you can check Hackaday or listen to Soma FM while you work). When the browser became visible, it would decide to be 1 pixel wide and 1 pixel high, which was not very useful. It took a lot of playing with making things visible and invisible and then visible again to get that working. In some cases, a timer will change something like the font size just barely, then change it back to trigger a recalculation after everything is visible.

Speaking of the browser, I didn’t want to have to use multiple pages with web browser components on it, so the system allows you to specify the same “page” more than once in the list. The page can have more than one title, based on its position, and you can initialize it differently, also based on its position. That was fairly easy, compared to getting them to draw correctly.

Other Gotchas

A few other problems cropped up, some of which aren’t the Inventor’s fault. For example, all phones are different, so your program gets resized differently, which makes it hard to work. I just told the interface I was building for a monitor and let the phone resize it. There’s no way to set a custom screen size that I could find.

The layout control is pretty crude, which makes sense. This is supposed to be a simple tool. There are no spacers or padding, for example, but small, fixed-size labels will do the job. There’s also no sane way to make an element span multiple cells in a layout, which leads to lots of deeply nested layouts.

The Bluetooth timeout in App Inventor seemed to act strangely, too. Sometimes it would time out even with ridiculously long timeout periods. I left it variable in the code, but if you change it to anything other than zero, good luck.

How’d It Work?

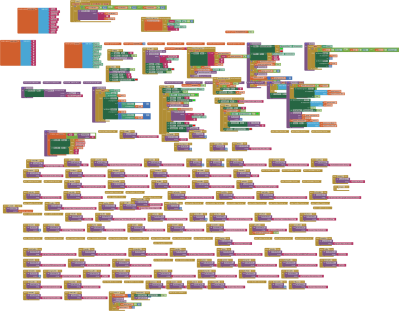

This is probably the most complex thing you’d want to do with App Inventor. The block structure is huge, although, to be fair, a lot of it is just sending a command off when you press a button. The example pad has nearly 500 blocks. The personalized version I use on my own phone (see the video below) has just over 900 blocks!

Of course, the tool isn’t made for such a scale, so be prepared for some development hiccups. The debugging won’t work after a certain point. You just have to build an APK, load it, and hope for luck.

You can find the demo on GitHub. My version is customized to link to my computer, on my exact screen size, and uses lots of local scripts, so I didn’t include it, but you can see it working in the video below.

If you want to go back and look more at the server mechanics, that was in the last post. Of, if you’d rather repurpose an old phone for a server, we’ve seen that done, too.

Omg I made the same talk to text feature in android unreleased as of yet. It was hard as heck setting up through wireless but works amazing, cant wait to check out the differences in this code, amazing work! This simplistic talk to text is a welcome needed feature for all.

I know that it’s just a toy project, but it’s a perfect example of how “security” is so easy to get wrong.

If arbitrary arguments (but not arbitrary commands) are allowed, the user can provide an argument like $(rm -rf /), effectively bypassing the commands whitelist.

I don’t think that is “wrong.” I think it is letting you select your risk tolerance. If you are worried about someone hacking into your Bluetooth connection and injecting commands into your computer then yes, turn off arbitrary commands and arguments. If you aren’t, then there you go. Choice. Honestly, I think if I have someone close enough to my office who can pair a device to my computer and send commands over the SPP, I probably have a lot of other things to worry about first. But since I know there are people who will accept virtually no risk I gave you the choice. Simple as that. Allowing arguments to the numeric commands is definitely a risk and one you have to assume at compile time if you choose to do so. Or lock it down.

Yes, exactly. The same tired old arguments of being over secure, patching OSes, even CPU microcode etc when the machine might be completely disconnected from all networks or never run a VM etc. Different use cases demand different levels of security, people who can not decide the level of security they need will be at risk irrespective. Don’t waste time making things secure if they don’t need it, it just adds latency, overhead, complexity etc.

I did some thing similar using auto it under windows for a tablet/phone based macro pad.

https://github.com/mmiscool/ShitDeck