If you built a car in, say, Germany, for use in Canada, you could assume that the roads will be more or less the same. Gravity will work the same. While the weather might not be exactly the same, it won’t be totally different. But imagine designing the Lunar Excursion Module that would land two astronauts on the moon for the first time. No one had any experience landing a craft on any alien body before.

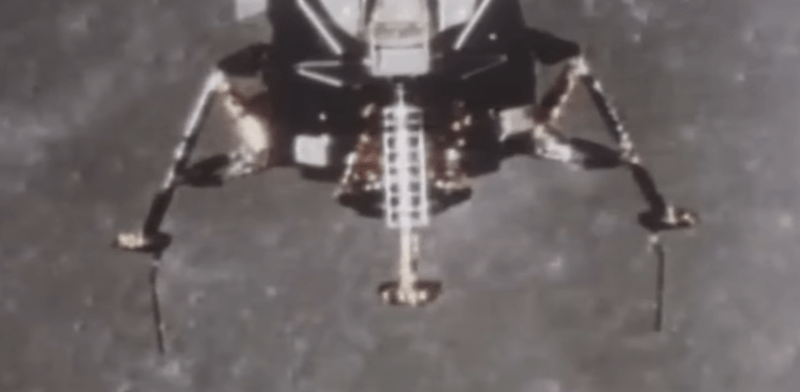

The LEM was amazing for many reasons, but as [Apollo11Space] points out, the legs were a particularly thorny engineering problem. They had to land on mostly unknown terrain, stay upright, allow for the ascent module to take off again, and, of course, not weigh down the tiny spaceship. They also had to survive the blast of the LEM’s engine.

Sure, there were some automated probes that landed in 1966 (the Soviets got there first, but NASA was just a few months behind). But by 1966, the first LEM was already three years old.

The video shows how many options were on the table, but the four-legged splayed footprint design was the winner. A Canadian company was instrumental in the successful production of the legs. One interesting thing is that the legs had a one-shot aluminum honeycomb shock absorber that destroyed itself as it absorbed the impact of landing.

It offers a fascinating glimpse into how it must have been to design something for the unknown, which couldn’t be properly tested until it was actually used. It was also fun to see the giant gantry they used to simulate lunar gravity for the test articles (that didn’t look much like the real thing, by the way).

The LEM famously served as a lifeboat for Apollo 13, but the legs probably didn’t matter for that. Of course, what we usually talk about is the amazing software onboard, but that’s only part of the story.

I had no idea that it was originally called LEM in English. I wonder if it was intended as a reference (backronym) to S. Lem, the Polish science fiction author.

I read that LEM was originally an acronym for Lunar Excursion Module, but NASA management decided to drop the word “excursion” as it “sounded too frivolous”. Despite the name being officially shortened to LM, people in NASA at the time still pronounced it “lem”.

Could have been pronounced as “el-em” to comply with LM only but I guess LEM stuck around like an old habit

That’s why I was thinking it might’ve been a reference originally, if it was called “LEM” (or “L(e)M”) by the NASA personnel even after the name change. But I cannot find anything about a connection to Lem, the author. Also, Lem was gaining popularity in the West in the 60s, with “Solaris” coming out in 1961, which is just on the money for referencing him in “Lunar Excursion Module”, but he might not have been “big” enough yet.

And as it happens this lucky lady was designed (we hope!) and built right here in New York and on Long Island.

Plot for LEM story: Two astronauts land on moon, later discovered fuel sufficient only for one to return. Hilarity ensues?

Sounds not unlike The Cold Equations.

“They also had to survive the blast of the LEM’s engine.” Gonna have to ask for more detail on that.

“allow for the ascent module to take off again” Other than just being there, how did they “allow” that? This sounds like a Physics 101 error I’ve seen before, the idea that rockets at whatever altitude push against the ground.

If one or more LEM legs are destroyed by the rocket exhaust while they are still supporting the Ascent Stage, things might go .. sideways.

And the rocket exhaust points at the legs because….. ?

The rocket exhaust points at the ground, which deflects it (and a large amount of abrasive moon dust/rocks/debris) sideways against the legs of the Lunar Module.

Two parts to that – first the engine used on decent to slow the craft. It’s just a big thruster, and the legs need to not be damaged by it.

Subsequently, the thrusters that yeet the capsule back into lunar orbit – these honestly just need a clear exhaust path.

Simple, yes, but high stakes and part of a complex machine. That’s the beauty of abstraction, we break complex problems down into a series of little ones that are actually solvable.

Legs were berylium. I knew a lady who welded them. Lois harvey.