The Hackaday Prize is almost over, and soon we’ll know the winners of the greatest hardware competition on the planet. A few weeks ago, we wrapped up the last challenge in the Hackaday Prize, the Musical Instrument Challenge. This is our challenge to build something that goes beyond traditional music instrumentation. Majenta’s back again looking at the coolest projects in the Musical Instrument Challenge in the Hackaday Prize.

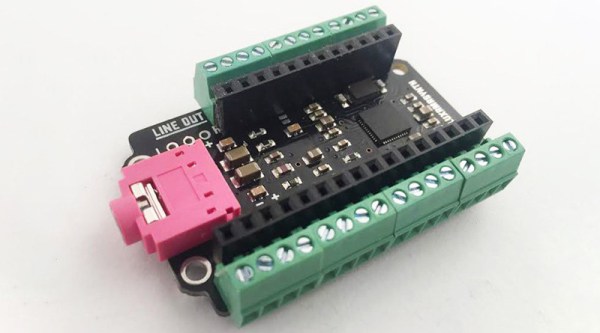

We’re old-school hardware hackers here, and when you think about building your own drum machine, there’s really nothing more impressive than building one out of an Atari 2600. That’s what [John Sutley] did with his Syndrum project. It’s a custom cartridge for an Atari with a fancy ZIF socket. Of course, you need some way to trigger those drum sounds, so [John] is using an Arduino connected to the controller port as a sort-of MIDI-to-Joystick bridge.

We’re old-school hardware hackers here, and when you think about building your own drum machine, there’s really nothing more impressive than building one out of an Atari 2600. That’s what [John Sutley] did with his Syndrum project. It’s a custom cartridge for an Atari with a fancy ZIF socket. Of course, you need some way to trigger those drum sounds, so [John] is using an Arduino connected to the controller port as a sort-of MIDI-to-Joystick bridge.

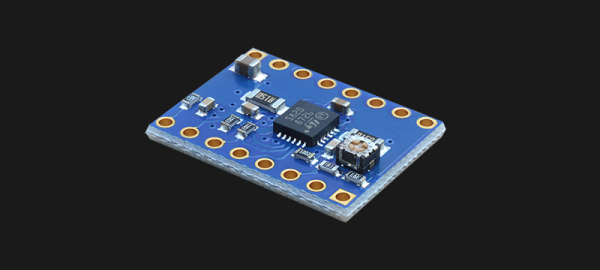

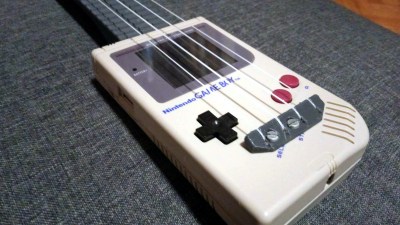

If you want more retro consoles turned into musical instruments, look no further than [Aristides]’ DMG-01 Ukulele. It’s a ukulele with a 3D printed neck, bolted onto the original ‘brick’ Game Boy. Yes, it works as a ukulele, but that’s not the cool part. There are electronics inside that sense each individual string and turn it into a distorted chiptune assault on the ears. Just awesome.

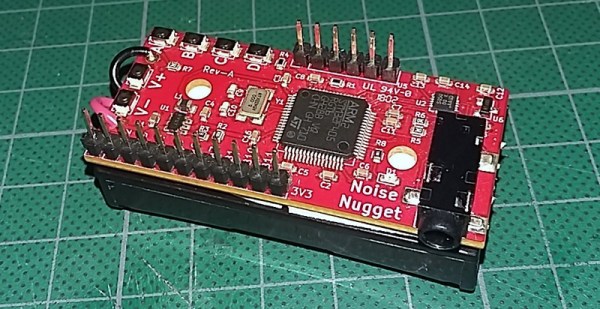

How about a unique, new musical instrument? That’s what [Tim] is doing with Stylish!, a wearable music synthesizer. It’s based heavily on a stylophone, but with a few interesting twists. It’s built around an STM32, so there are a lot of options for what this instrument sounds like, and it’s all wrapped up in a beautiful enclosure. It’s some of the best work we’ve seen in this year’s Musical Instrument Challenge.

The Hackaday Prize is almost over, and on Saturday we’ll be announcing the winners at this year’s Hackaday Superconference. Tune in to the live stream to see which project will walk away with the grand prize of $50,000!