Recently, the EPA and COBB Tuning have settled after the latter was sued for providing emissions control defeating equipment. As per the EPA’s settlement details document, COBB Tuning have since 2015 provided customers with the means to disable certain emission controls in cars, in addition to selling aftermarket exhaust pipes with insufficient catalytic systems. As part of the settlement, COBB Tuning will have to destroy any remaining device, delete any such features from its custom tuning software and otherwise take measures to fully comply with the Clean Air Act, in addition to paying a $2,914,000 civil fine.

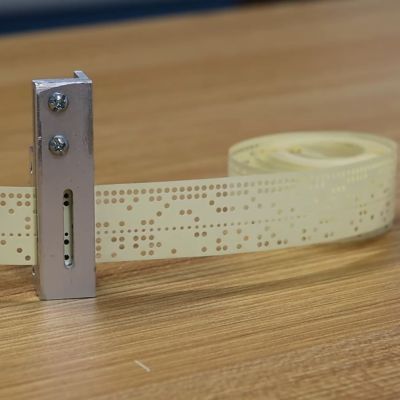

The tuning of cars has come a long way from the 1960s when tweaking the carburetor air-fuel ratios was the way to get more power. These days cars not only have multiple layers of computers and sensor systems that constantly monitor and tweak the car’s systems, they also have a myriad of emission controls, ranging from permissible air-fuel ratios to catalytic converters. It’s little surprise that these systems can significantly impact the raw performance one might extract from a car’s engine, but if the exhaust of nitrogen-oxides and other pollutants is to be kept within legal limits, simply deleting these limits is not a permissible option.

COBB Tuning proclaimed that they weren’t aware of these issues, and that they never marketed these features as ’emission controls defeating’. They were however aware of issues regarding their products, which is why they announced ‘Project Green Speed’ in 2022, which supposedly would have brought COBB into compliance. Now it would seem that the EPA did find fault despite this, and COBB was forced to making adjustments.

Although perhaps not as egregious as modifying diesel trucks to ‘roll coal’, federal law has made it abundantly clear that if you really want to have fun tweaking and tuning your car without pesky environmental laws getting in the way, you could consider switching to electric drivetrains, even if they’re mind-numbingly easy to make performant compared to internal combustion engines.