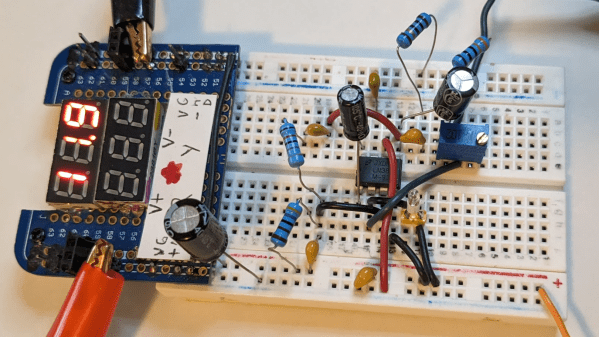

[mircemk] had previously built a frequency counter using an Arduino, with a useful range up to 6 MHz. Now, they’ve implemented a new design on a far more powerful STM32 chip that boosts the measurement range up to a full 30 MHz. That makes it a perfect tool for working with radios in the HF range.

The project is relatively simple to construct, with an STM32F103C6 or C8 development board used as the brains of the operation. It’s paired with old-school LED 7-segment displays for showing the measured frequency. Just one capacitor is used as input circuitry for the microcontroller, which can accept signals from 0.5 to 3V in amplitude. [mircemk] notes that the circuit would be more versatile with a more advanced input circuit to allow it to work with a wider range of signals.

It’s probably not the most accurate frequency counter out there, and you’d probably want to calibrate it using a known-good frequency source once you’ve built it. Regardless, it’s a cheap way to get one on your desk, and a great way to learn about measuring and working with time-varying signals. You might like to take a look at the earlier build from [mircemk] for further inspiration. Video after the break.

Continue reading “Simple STM32 Frequency Meter Handles Up To 30MHz With Ease”

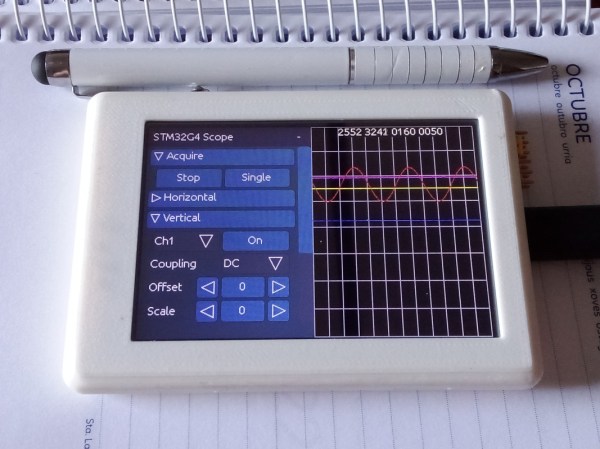

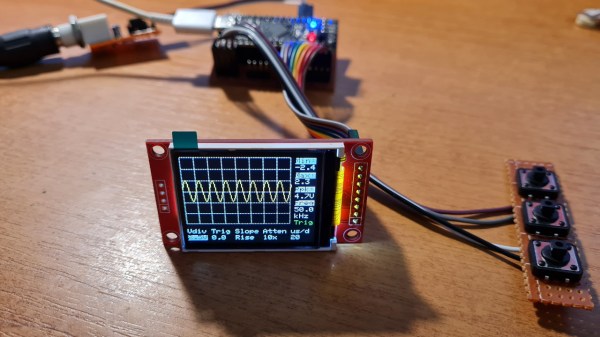

It’s hard to overshadow just how easy this scope is to build, use, and hack on. You really don’t need much in the way of parts, a protoboard will do, though you can also etch or order

It’s hard to overshadow just how easy this scope is to build, use, and hack on. You really don’t need much in the way of parts, a protoboard will do, though you can also etch or order