There are few computing collapses more spectacular than the downfall of Commodore, but its rise as a home computer powerhouse in the early 80s was equally impressive. Driven initially by the VIC-20, this was the first home computer model to sell over a million units thanks to its low cost and accessibility for people outside of niche markets and hobbyist communities.

The VIC-20 would quickly be eclipsed by the much more famous Commodore 64, but for those still using these older machines there are a few tweaks to give it some extra functionality it was never originally designed for like this build which gives it an ISA bus.

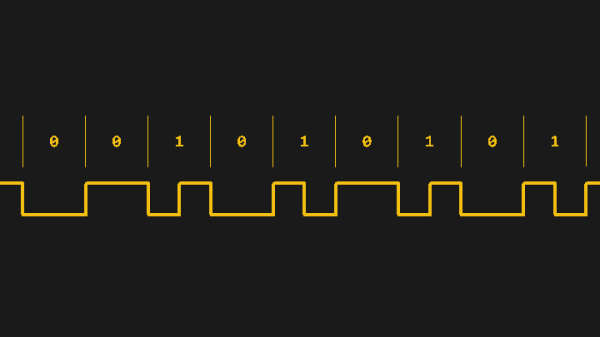

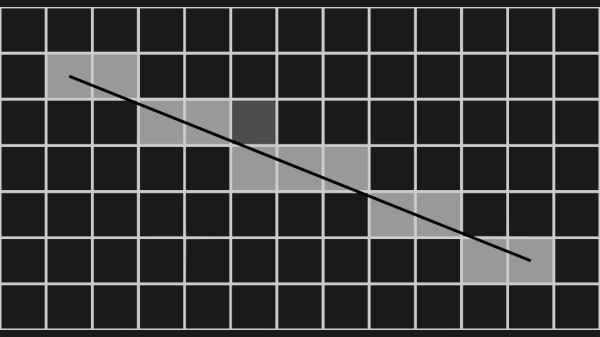

To begin adapting the VIC-20 to the ISA standard, [Lee] built a fixed interrupt line handled with a simple transistor circuit. From there he started mapping memory and timing signals. The first attempt to find a portion of memory to use failed as it wasn’t as unused as he had thought, but eventually he settled on using the I/O area instead although still had to solve some problems with quirky ISA timing. There’s also a programmable logic chip which was needed to generate three additional signals for proper communication.

After solving some other issues around interrupts [Lee] was finally able to get the ISA bus working, specifically so he could add a 3Com networking card and get his VIC-20 on his LAN. Although the ISA bus has since gone out of fashion on modern computers, if you still have a computer with one (or build one onto your VIC-20), it is a surprisingly versatile expansion port.

Thanks to [Stephen] for the tip!