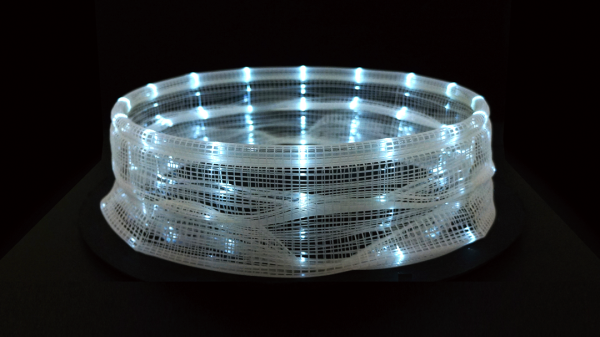

This fascinating project manages to be both something new and something old done in a new way. Artist [Akinori Goto] has used 3D printing to create a sort of frameless zoetrope. It consists of a short animation of a human figure, but the 3D movements of that figure through time are “smeared” across a circular zone – instead of the movements of the figure being captured as individual figures or frames, they are combined into a single object, in a way squashing 4 dimensions into 3.

“Slices” of that object, when illuminated by a thin shaft of light, reveal the figure’s pose at a particular moment in time. When the object is spun while illuminated in this way, the figure appears to be animated in a manner very similar to a zoetrope.

“Slices” of that object, when illuminated by a thin shaft of light, reveal the figure’s pose at a particular moment in time. When the object is spun while illuminated in this way, the figure appears to be animated in a manner very similar to a zoetrope.

There are two versions from [Akinori Goto] that we were able to find. The one shown above is a human figure walking, but there is a more recent and more ambitious version showing a dancer in motion, embedded below.

Since a thin ray of light is used to illuminate a single slice of the sculpture at a time, it’s also possible to use multiple points of illumination – or even move them – for different visual effects. Check out the videos below to see these in action.

Continue reading “3D Printed Zoetrope Sculpture Squashes 4 Dimensions Into 3”