How many plastic spoons, knives, and forks do you think we throw away daily? [Stefan] noted that the compostable type is made from PLA, so why shouldn’t you be able to recycle it into 3D printing stock? How did it work? Check it out in the video below.

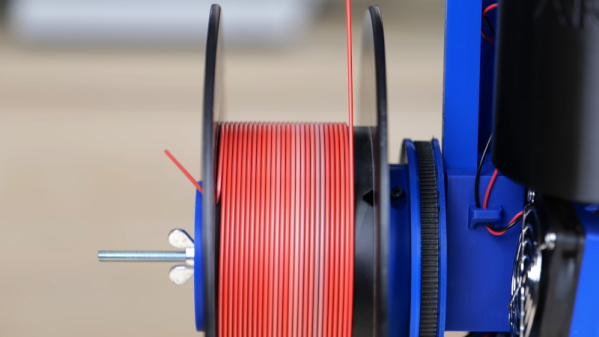

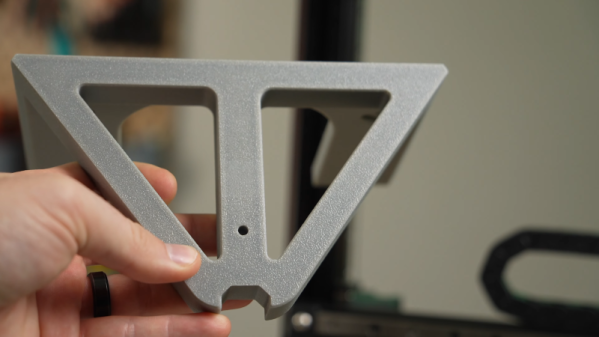

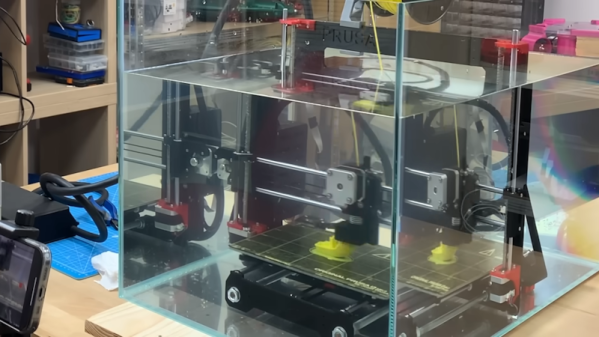

[Stefan] already has a nice setup for extruding filament. However, unsurprisingly, it won’t accept spoons and forks directly. A blender didn’t help, so he used an industrial plastic shredder. It reduced the utensils to what looked like coarse dust, which he then dried out. After running it through the extruder, the resulting filament was thin and brittle. [Stefan] speculates the plastic was set up for injection molding, but it at least showed the concept had merit.

In a second attempt, he cut the ground-up utensils with fresh PLA in equal measures. That is, 50% of the mix was recycled, and half was not. That made much more usable filament. So did a different brand of compostable plasticware.

The real test was to take dirty plasticware. This time, he soaked utensils in tomato sauce overnight. He cleaned, dried, and shredded the plastic. This time, he used 20% new PLA and some pigment, as well. We aren’t sure this is worth the effort simply on economics, but if you are committed to recycling, this might be worth your while.

It always seems like it should be easy to extrude filament. Until you try to do it, of course. Recycling plastic bottles is especially popular.

Continue reading “3D Printing With Plastic Cutlery” →