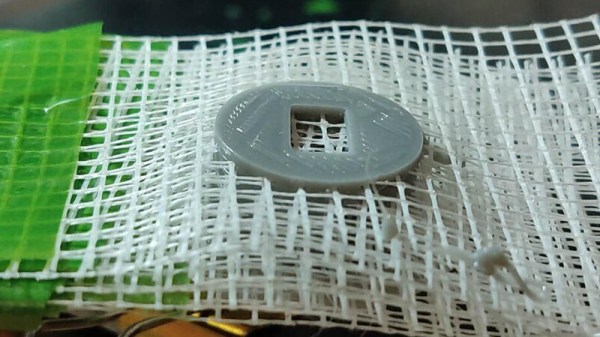

Anyone who has done any amount of 3D printing with SLA printers is probably well aware of the peeling step with each layer. This involves the newly printed layer being pulled away from the FEP film that is attached to the bottom of the resin vat. Due to the forces involved, the retraction speed of the build plate on the Z-axis has to be carefully tuned to not have something terrible happen, like the object being pulled off the build plate. Ultimately this is what limits SLA print speed, yet [Jan Mrázek] postulates that replacing the FEP with an oxygen-rich layer can help here.

The principle is relatively simple: the presence of oxygen inhibits the curing of resin, which is why for fast curing of resin parts you want to do so in a low oxygen environment, such as when submerged in water. Commercial printers by Carbon use a patented method called “continuous liquid interface production” (CLIP), with resin printers by other companies using a variety of other (also patented) methods that reduce or remove the need for peeling. Theoretically by using an oxygen-permeating layer instead of the FEP film, even a consumer grade SLA printer can skip the peeling step.

The initial attempt by [Jan] to create an oxygen-permeating silicone film to replace the FEP film worked great for about 10 layers, until it seems the oxygen available to the resin ran out and the peeling force became too much. Next attempts involved trying to create an oxygen replenishment mechanism, but unfortunately without much success so far.

Regardless of these setbacks, it’s an interesting research direction that could make cheap consumer-level SLA printers that much more efficient.

(Thumbnail image: the silicone sheet prior to attaching. Heading image: the silicone sheet attached to a resin vat. Both images by [Jan Mrázek])

[HolGer71] starts with

[HolGer71] starts with