Aside from a few stand-out programs — looking at you, Star Trek — by the late 1960s, TV had already become the “vast wasteland” predicted almost a decade earlier by Newton Minnow. But for the technically inclined, the period offered no end of engaging content in the form of wall-to-wall coverage of anything and everything to do with the run-up to the Apollo moon landings. It was the best thing on TV, and even the endless press conferences beat watching a rerun of Gilligan’s Island.

At the time, most of the attention landed on the manned missions, with the photogenic and courageous astronauts of the Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo programs very much in the limelight. But for our money, it was the unmanned missions where the real heroics were on display, starring the less-photogenic but arguably vastly more important engineers and scientists who made it all possible. It probably didn’t do much for the general public, but it sure inspired a generation of future scientists and engineers.

With that in mind, we were pleased to see this Surveyor 1 documentary from Retro Space HD pop up in our feed the other day. It appears to be a compilation of news coverage and documentaries about the mission, which took place in the summer of 1966 and became the first lunar lander to set down softly on the Moon’s surface. The rationale of the mission boiled down to one simple fact: we had no idea what the properties of the lunar surface were. The Surveyor program was designed to take the lay of the land, and Surveyor 1 in particular was tasked with exploring the mechanical properties of the lunar regolith, primarily to make sure that the Apollo astronauts wouldn’t be swallowed whole when they eventually made the trip President Kennedy had mandated back in 1961.

The video below really captures the spirit of these early missions, a time when there were far more unknowns than knowns, and disaster always seemed to be right around the corner. Even the launch system for Surveyor, the Atlas-Centaur booster, was a wild card, having only recently emerged from an accelerated testing program that was rife with spectacular failures. The other thing the film captures well is the spacecraft’s nail-biting descent and landing, attended not only by the short-sleeved and skinny-tied engineers but by a large number of obvious civilians, including a few lucky children. They were all there to witness history and see the first grainy but glorious pictures from the Moon, captured by a craft that seemed to have only just barely gotten there in one piece.

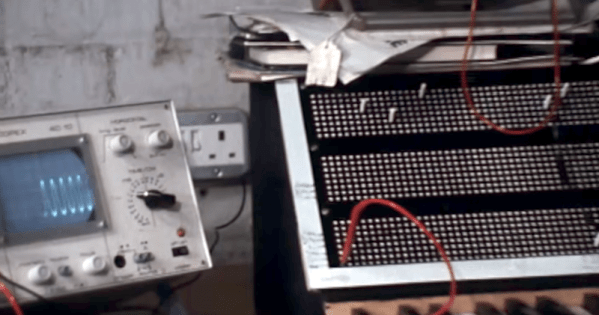

The film is loaded with vintage tech gems, of course, along with classic examples of the animations used at the time to illustrate the abstract concepts of spaceflight to the general public. These sequences really bring back the excitement of the time, at least for those of us whose imaginations were captured by the space program and the deeds of these nervous men and women.

NASA wants to return to the moon. They also want you to help. Turns out making a good landing on the moon is harder than you might think.

Continue reading “Retrotechtacular: Exploring The Moon On Surveyor 1“ →