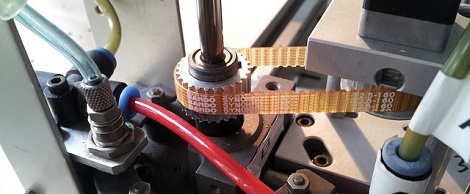

It looks like Null Space Labs has a new pick and place machine. This immense repair job began when [Charliex] and [Gleep] found a JukiPlacemat 360 pick and place machine. The idea of having their very own pick and place machine proved intoxicating, possibly too much so because the didn’t return the machine when they found out it wasn’t working.

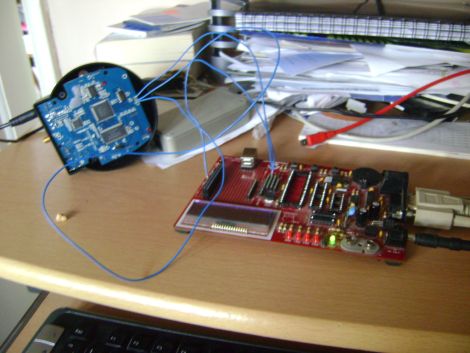

After a ton of work that involved adding a camera, [Charliex] and the rest of the builders at Null Space Labs finally have their own pick and place machine that works. This was a complete rebuild from the ground up. So many things didn’t work on the machine, they might have been better off building one from scratch. Aside from the massive effort that went into turning the shell of a machine into a working unit, we really have to commend everyone who worked on it.

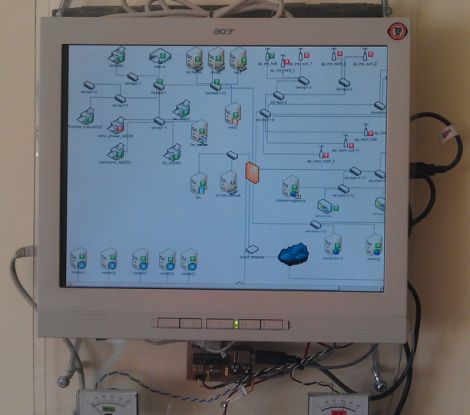

The team added a nice GUI to control the machine. The guys have already run a successful test and ovened a few boards, so everything works as it should have at purchase. It’ll be great for making next year’s LayerOne conference badges.