Building a Commodore 64 is among the easier projects for retrocomputing fans to tackle. That’s because the C64’s core chipset does most of the heavy lifting; source those and you’re probably 80% of the way there. But what if you can’t find those chips, or if you want more of a challenge than plugging and chugging? Are you out of luck?

Hardly. The video below from [DrMattRegan] is the first in a series on his scratch-built C64 that doesn’t use the core chipset, and it looks pretty promising. This video concentrates on building a replacement for the 6502 microprocessor — actually the 6510, but close enough — using just a couple of EPROMs, some SRAM chips, and a few standard logic chips to glue everything together. He uses the EPROMs as a “rulebook” that contains the code to emulate the 6502 — derived from his earlier Turing 6502 project — and the SRAM chips as a “notebook” for scratch memory and registers to make a Turing-complete random access machine.

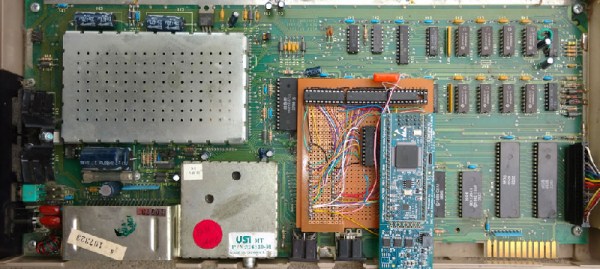

[DrMatt] has made good progress so far, with the core 6502 CPU built on a PCB and able to run the Apple II version of Pac-Man as a benchmark. We’re looking forward to the rest of this series, but in the meantime, a look back at his VIC-less VIC-20 project might be informative.

Continue reading “A Scratch-Built Commodore 64, Turing Style”