We love camera hacking here at Hackaday, and it’s always fascinating to see new things being done in photography. Something rather special has come our way from [Camerdactyl], who hasn’t merely made a camera, instead he’s created an entirely new analogue film format. Move over 35mm and 120, here’s the RA-4 cartridge!

RA-4 is the colour print chemistry many of you will be familiar with from your holiday snaps back in the day. Normally a negative image is projected onto it from the negative your camera took, and the positive image is developed on the paper as the reverse of that. It can also be developed as a reversal process similar to slide film, in which the negative image is developed and bleached away leaving an unexposed positive image, which can then be exposed to light and developed to reveal a picture. This means that with carefully chosen colour correction filters it can be shot in a camera to make normal colour prints with this reversal process.

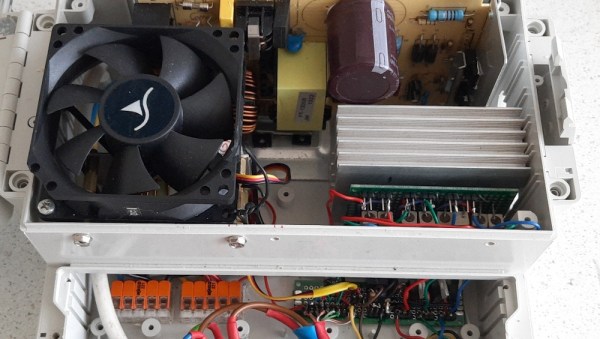

The new film format is a 3D printed cartridge system holding a long roll of RA-4 paper, which slots into a back for standard 5 by 4 inch cameras. He’s also made a modular developing machine for the process, and can get over 100 shots on a roll. A portion of the video below deals with how he wants to release it; since it has taken a huge amount of development resources he intends to release the files to the public in stages as he reaches sales milestones with his work. It’s an unusual strategy that we hope works for him, though we suspect that many camera hackers would be prepared to pay him directly for the files.

Either way, it’s a reminder that there’s still plenty of fun to be had with analogue film, and also that reversal development of RA-4 is possible. Some of us here at Hackaday have been known to hack a few cameras, we guess it’s another one to add to the “one day” list.