You’ve built a brand new project, and it’s a wonderful little thing that’s out and about in the world. The only problem is, you need to know its location to a decent degree of accuracy. Thankfully, GPS is a thing! With an off-the-shelf module, it’s possible to get all the location data you could possibly need. But how do you go about it, and what parts are the right ones for your application? For the answers to these questions, read on! Continue reading “How To Choose The Right GPS Module For Your Project”

Beidou5 Articles

Not Just GPS: New Options For Global Positioning

A few weeks ago, China launched the final satellite in its BeiDou-3 satellite positioning system. Didn’t know that China had its own GPS? How about Europe’s Galileo, Russia’s GLONASS, or Japan’s QZSS? There’s a whole world of GPS-alikes out there. Let’s take a look.

Continue reading “Not Just GPS: New Options For Global Positioning”

Homemade Subaru Head Unit Is Hidden Masterpiece

The Subaru BRZ (also produced for Toyota as the GT86) is a snappy sportster but [megahercas6]’s old US version had many navigation and entertainment system features which weren’t useful or wouldn’t work in his native Lithuania. He could have swapped out the built in screen for a large 4G Android tablet/phone, but there’s limited adventure in that. Instead, he went ahead and built his own homemade Navigation system by designing and integrating a whole bunch of hardware modules resulting in one “hack” of an upgrade.

The system is built around a Lenovo 4G phone-tablet running android and supporting GPS, GLONASS as well as the Chinese BeiDou satellite navigation systems. He removed the original daughter board handling the USB OTG connection on the tablet, and replaced it with his version so he could connect it to his external USB board via a flat ribbon cable. The USB board contains a Cypress 4-port USB hub. One port is used as the USB HID device to allow external buttons for system control — Power, Volume Up/Down, Fwd/Rev, Play/Pause, and Phone Answer/Hangup. The second port is used as a regular USB input to allow connecting external devices such as flash drives. The third one goes to a reversing camera while the fourth port goes to a USB DAC.

The USB DAC is another hardware board by itself and also includes a Bluetooth module which integrates his phone’s audio and control functions with the on-board system. There’s also an audio mixer which allows him to use the phone audio without having to miss out on the navigation prompts from the tablet. Both boards also contain several peripheral circuits such as amplifiers and DC power supplies. Audio to the speakers is routed through six LM3886 based power amplifier boards. And the GPS module receives its own special low-noise amplifier board to ensure extremely strong reception at all times. That’s a total of ten boards custom built for this project. He’s also managed to source all the original harness connectors so his system is literally a snap in replacement. The final assembly looks pretty dashing.

For some strange reason, the Lenovo tablet uses 4.35V as the ‘fully charged” value for its LiPo instead of the more common 4.20V, so even with the whole system connected to a hefty 12V lead acid battery from which he’s deriving the 4.20V charging voltage for the tablet, it still complains about “low battery” — and he’s looking for advice on how he can resolve that issue short of blowing up the LiPo by using the higher charge voltage. Besides that, he’s (obviously a kickass) hardware designer and a little bit rusty on the software and programming side of things, for which he’s looking for inputs from the community. His introductory video is almost 30 minutes long, but the shorter demo video after the break shows the system after installation in his car. He’s posted all of his Altium hardware source files on the project page, but until he shares PDF versions, it would be difficult for most of us to look at his work.

Continue reading “Homemade Subaru Head Unit Is Hidden Masterpiece”

Arduino TinyGPS Updated To Support GLONASS

GPS is a global technology these days, with the Russian GLONASS system and the forthcoming European Galileo orbiting alongside the original US GPS satellites above our heads. [Florin Duroiu] decided to embrace globalism by forking the TinyGPS library for the Arduino platform to add support for these satellite constellations.

In addition to the GLONASS support, the new version of the venerable TinyGPS adds some neat new features by incorporating the NMEA 3.0 standard (warning: big-ass PDF link). Using this, you can extract interesting stuff such as the calculated position from each satellite constellation, the signal strength of each satellite and a lot more technical stuff about what the satellites are saying about you to your GPS receiver. [Florin] claims it is a drop-in replacement for TinyGPS that should require no rewriting. There is no support for Galileo just yet (as the satellites are still being launched: eight are in orbit now), but [Florin] is looking for help to add this, as well as the new Chinese BEIDOU system once it is operational.

(top image: artists’ view of a Galileo satellite in orbit, courtesy of ESA)

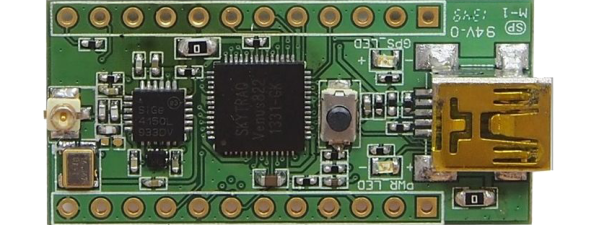

$20 GPS/GLONASS/Beidou Receiver

Sticking a GPS module in a project has been a common occurrence for a while now, whether it be for a reverse geocache or for a drone telemetry system. These GPS modules are expensive, though, and they only listen in on GPS satellites – not the Russian GLONASS satellites or the Chinese Beidou satellites. NavSpark has the capability to listen to all these positioning systems, all while being an Arduino-compatible board that costs about $20.

Inside the NavSpark is a 32-bit microcontroller core (no, not ARM. LEON) with 1 MB of Flash 212kB of RAM, and a whole lot of horsepower. Tacked onto this core is a GPS unit that’s capable of listening in on GPS, GPS and GLONASS, or GPS and Beidou signals.

On paper, it’s an extremely impressive board for any application that needs any sort of global positioning and a powerful microcontroller. There’s also the option of using two of these boards and active antennas to capture carrier phase information, bringing the accuracy of this setup down to a few centimeters. Very cool, indeed.

Thanks [Steve] for sending this in.