You can get electricity from just about anything. That old crystal radio kit you built as a kid taught you that, but how about doing something a little more interesting than listening to the local AM station with an earpiece connected to a radiator? That’s what the Electron Bucket is aiming to do. It’s a power harvesting device that grabs electricity from just about anywhere, whether it’s a piece of aluminum foil or a bunch of LEDs.

The basic idea behind the Electron Bucket is to harvest ambient radio waves just like your old crystal radio kit. There’s a voltage doubler, a rectifier, and as a slight twist, a power management circuit that would normally be found in battery-powered electronics.

Of course, this circuit can do more than harvesting electricity from ambient radio waves. By connecting a bunch of LEDs together, it’s possible to send a few Bluetooth packets around. This is pretty impressive — the circuit is using LEDs as solar cells, which normally produce about 50nA of current at 0.5V in direct sunlight. By connecting 12 LEDs in parallel and series, it manages to harvest just enough energy to run a small wireless module. That’s impressive, and an interesting entry to the Power Harvesting Challenge in this year’s Hackaday Prize.

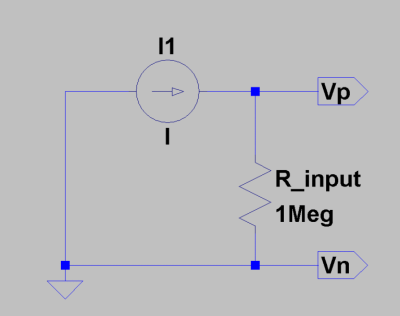

As you might expect, a common digital meter’s current scales aren’t usually up to measuring nano- or pico-amps. [Danny’s] approach was not to use the ammeter scale. Instead, he measures the voltage developed across the input impedance of the meter (which is usually very high, like one megaohm). If you know the input characteristics of the meter (or can calibrate against a known source), you can convert the voltage to a current.

As you might expect, a common digital meter’s current scales aren’t usually up to measuring nano- or pico-amps. [Danny’s] approach was not to use the ammeter scale. Instead, he measures the voltage developed across the input impedance of the meter (which is usually very high, like one megaohm). If you know the input characteristics of the meter (or can calibrate against a known source), you can convert the voltage to a current.