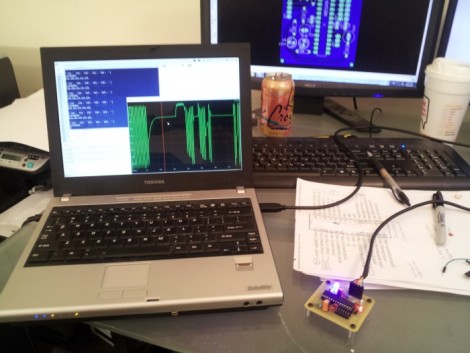

[Scott Harden] has already produced some projects which measure analog inputs. But he’s got plans for more and wanted a base system for graphing analog signals. You can see the small board next to his laptop which offers the ability to sample up to six signals and push them to a PC via USB.

The ATmega48 and a few supporting components are all you’ll find on that board. The USB connection is taken care of by an FTDI cable. He went that route because the cables are relatively cheap, easy to come by, and already have driver support on all the major operating systems. If you look at the screen you can see a window graphing one analog input in real-time. He wrote this in Python (which is once again a cross-platform tool) and it has no problem graphing all six inputs at once.

This is immediately useful as an upgrade to [Scott’s] ECG machine. His future plans include a Pulse Oximeter, EEG, and EEG.