Although the idea of containing a plasma within a magnetic field seems straightforward at first, plasmas are highly dynamic systems that will happily escape magnetic confinement if given half a chance. This poses a major problem in nuclear fusion reactors and similar, where escaping particles like alpha (helium) particles from the magnetic containment will erode the reactor wall, among other issues. For stellarators in particular the plasma dynamics are calculated as precisely as possible so that the magnetic field works with rather than against the plasma motion, with so far pretty good results.

Now researchers at the University of Texas reckon that they can improve on these plasma system calculations with a new, more precise and efficient method. Their suggested non-perturbative guiding center model is published in (paywalled) Physical Review Letters, with a preprint available on Arxiv.

The current perturbative guiding center model admittedly works well enough that even the article authors admit to e.g. Wendelstein 7-X being within a few % of being perfectly optimized. While we wouldn’t dare to take a poke at what exactly this ‘data-driven symmetry theory’ approach exactly does differently, it suggests the use machine-learning based on simulation data, which then presumably does a better job at describing the movement of alpha particles through the magnetic field than traditional simulations.

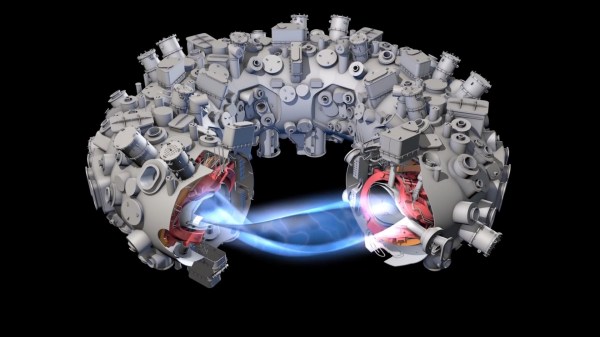

Top image: Interior of the Wendelstein 7-X stellarator during maintenance.