There are millions of devices and sensors connected to the Internet, and the next decade will bring billions more. How will anyone keep track of all these sensors? With analog.io, a platform for IoT devices, and [Luke]’s entry for The Hackaday Prize.

The problem of aggregating data from an Internet of things has been tackled before. Last year, Sparkfun released data.sparkfun.com, built on Phant, a tool for collecting data from the Internet of Things. Even though Phant can collect the data, it only does this in neat columns with values and time stamps. To turn this into something a little more visual, analog.io was born. In the future, [Luke] will add support for thingspeak and Xively data streams; the entire project is intended to be backend agnostic, allowing anyone to get their data from any thing, store it on any server, and connect it to analog.io for visualization and sharing.

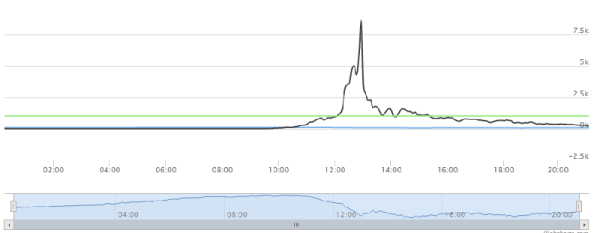

Graphing data provides for some interesting opportunities, like when [Luke] found his Internet-connected water meter was logging far, far too much water consumption. A fitting on a garden hose came loose, and the hose started pouring water onto the ground, a foot away from his basement wall. That’s a swimming pool’s worth of water on [Luke]’s foundation, easily and readily graphed. He’s now adding an alert feature to analog.io.

Graphing data does present its own problems, like when a sensor sends a single erroneous data point. [Luke] is calling this a ‘burr’, and analog.io can filter out these small spikes that make data unreadable as a graph. There’s a lot of work that goes into making a usable graph, and [Luke] is crossing all his ‘t’s and dotting all his lowercase ‘j’s.

While many of the entries for the Hackaday Prize are running at the ground level with individual sensors connected to the Internet, [Luke]’s project tackles the Internet of Things problem from the other end, providing everyone a way to easily visualize their data. It’s a great Hackaday Prize entry, and will surely come in useful for a number of other prize entries as well.