When you’ve got a piece of interesting old aviation hardware on your desk, what do you do with it? If you’re not willing to relegate it to paperweight status, your only real choice is to tear it down to see what makes it tick. And if you’re lucky, you’ll be able to put it to work based on what you learned.

That’s what happened when [Glen Akins] came across a tachometer for a jet airplane, which he promptly turned into a unique CPU utilization gauge for his computer. Much of the write-up is concerned with probing the instrument’s innards to learn its secrets, although it was clear from the outset that his tachometer, from Kollsman Instruments, was electrically driven. [Glen]’s investigation revealed a 3-phase synchronous motor inside the tach. The motor drives a permanent magnet, which spins inside a copper cup attached to the needle on the tach’s face. Eddy currents induced in the cup by the spinning magnet create a torque that turns the needle against the force of a hairspring. Pretty simple — but how to put the instrument to work?

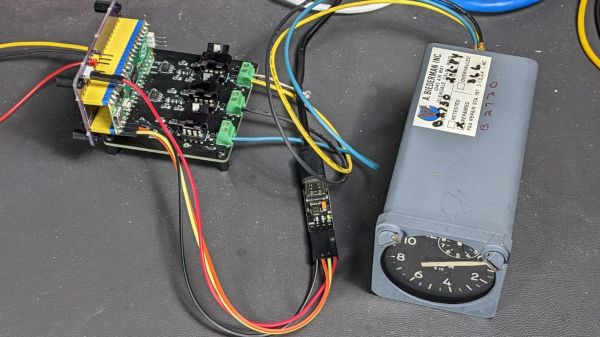

[Glen]’s solution was to build what amounts to a variable frequency drive (VFD). His power supply is based on techniques he used to explore aircraft synchros, which we covered a while back. The drive uses a trio of MCP4802 8-bit DACs to generate three phase-shifted sine waves via direct digital synthesis with an RP2040. The 3-phase signal drives the motor and spins the dial, with 84-Hz corresponding to full-scale deflection.

The video below shows the resulting CPU utilization gauge — which just queries for the current load level and sends it to the RP2040 over serial — in action. It’s not exactly responsive to rapid changes, but that’s to be expected from a mechanical system. And compared to exploring such a nice instrument, it really doesn’t matter.

Continue reading “Jet Engine Tachometer Turned Into Unique CPU Utilization Meter”