[Larsim] worked out the timing necessary to read button and joystick data from an N64 controller using an ATtiny85 microcontroller. The project was spawned when he found this pair of controllers in the dumpster. We often intercept great stuff bound for the landfill, especially on Hippie Christmas when all the student switch apartments at the same time.

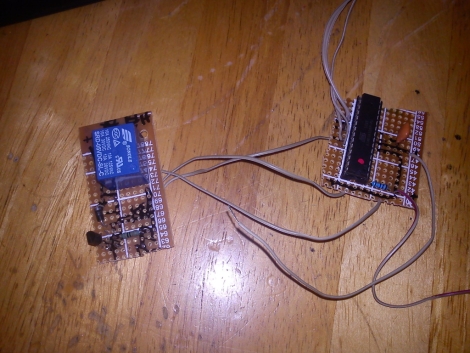

Instead of cracking the controllers open and patching directly to the buttons, [Larsim] looked up the pinout of the connector and patched into the serial data wire. In true hacker fashion, he used two 5V linear regulators and a diode in series to step his voltage source down to close to 3.6V, as he didn’t have a variable regulator on hand. It does sound like this causes noise which can result if false readings, but that can be fixed with the next parts order.

The controller waits for a polling signal before echoing back a response in which button data is embedded. This process is extremely quick, and without a crystal on hand, the chip needs to be configured to use its internal PLL to ramp the R/C oscillator up to 16Mhz. With the chip now running fast enough, an external interrupt reads the serial response from the controller, and the code reacts based on that input.

It seems the biggest reason these N64 controllers hit the trash can is because the analog joystick wears out. If you’ve got mad skills you can replace it with a different type.