In the 1950s and 1960s, the prospects for a future powered by nuclear energy were bright. There had been accidents at nuclear reactors, but they had not penetrated the public consciousness, or had conveniently happened far away. This was the age of “Too cheap to meter“, and The Jetsons, in which a future driven by technologies as yet undreamed of would free mankind from its problems. Names like Three Mile Island, Chernobyl, and Fukushima were unheard of, and it seemed that nuclear reactors would become the miracle power source for the second half of the twentieth century and beyond.

The first generation of nuclear power stations were thus accompanied by extremely optimistic public relations and news coverage. At the opening of the world’s first industrial-scale nuclear power station at Calder Hall, UK in 1956, the [Queen] gave a speech in which she praised it as for the common good of the community, and on the other side of the Atlantic the American nuclear industry commissioned slick public relations films to promote their work. Such a film is the subject of this piece, and though unlike the British they could not muster a monarch, had they but known it at the time they did employ the services of a President.

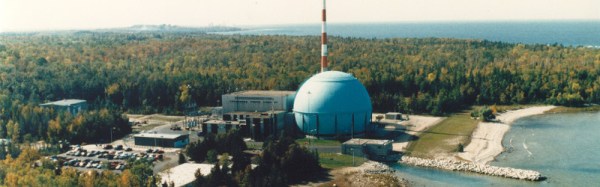

The Big Rock Point nuclear power plant was completed in 1962 on the shores of Lake Michigan. Its owners, Consumers Power Company, were proud of their new facility, and commissioned a short film about it. The reactor had been supplied by General Electric, and fronting the film was General Electric’s established spokesman and host of their General Electric Theater TV show, the Hollywood actor and future President [Ronald Reagan].

The film below the break starts by explaining nuclear power as a new heat source powering a conventional steam-driven generator, and stresses the safety aspect of reactor control rods. We are then treated to a fascinating view of the assembly of an early-1960s nuclear reactor, starting with the arrival of the pressure vessel and showing the assemblies within it that held the fuel and control rods. Fuel rods are shown at their factory in California, and being loaded onto a truck to be shipped across the continent, seemingly without the massive security that would nowadays accompany such an undertaking. The rods are loaded and the reactor is started, as [Reagan] puts it: “The atom has been put to work, on schedule”.

Fail of the Week is a Hackaday column which celebrates failure as a learning tool. Help keep the fun rolling by writing about your own failures and

Fail of the Week is a Hackaday column which celebrates failure as a learning tool. Help keep the fun rolling by writing about your own failures and