Look around yourself right now and chances are pretty good that you’ll quickly lay eyes on a zipper. Zippers are incredibly commonplace artifacts, a commodity item produced by the mile that we rarely give a second thought to until they break or get stuck. But zippers are a fairly modern convenience, and the story of their invention is one that shows even the best ideas can be delayed by overly complicated designs and lack of a practical method for manufacturing.

Try and Try Again

Ideas for fasteners to replace buttons and laces have been kicking around since the mid-19th century. The first patent for a zipper-like fastener was issued to Elias Howe, inventor of the sewing machine. Though he was no slouch at engineering intricate mechanisms, Howe was never able to make his “Automatic, Continuous Clothing Closure” a workable product, and Howe shifted his inventive energies to other projects.

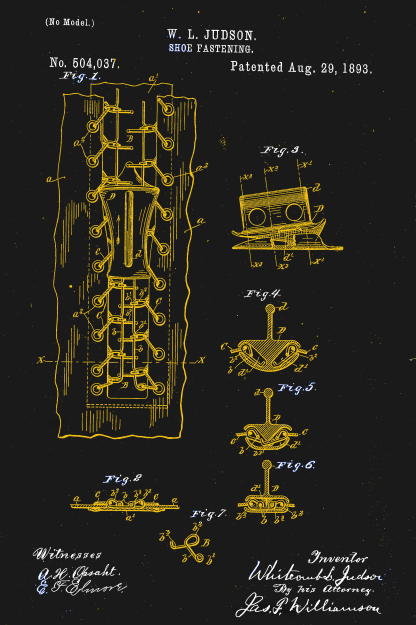

The world would wait another forty years for further development of a hookless fastener, when a Chicago-born inventor of little prior success named Whitcomb Judson began work on a “Clasp Locker or Unlocker.” Intended for the shoe and boot market, Judson’s device has all the recognizable parts of a modern zipper — rows of interlocking teeth with a slide mechanism to mesh and unmesh the two sides. The device was debuted at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893 and was met with almost no commercial interest.

Judson went through several iterations of designs for his clasp locker, looking for the right combination of ideas that would result in a workable fastener that was easy enough to manufacture profitably. He lined up backers, formed a company, and marketed various versions of his improved products. But everything he tried seemed to have one or more serious drawbacks. When his fasteners were used in shoes, unexpected failure was a mere inconvenience. If a fastener on a lady’s dress opened unexpectedly, it could have been a social catastrophe. Coupled with a price tag that was exorbitantly high to cover the manual labor needed to assemble them, almost every version of Judson’s invention flopped.

It would take another decade, a change of company name, a cross-country move, and the hiring of a bright young engineer before the world would have what we would recognize as the first modern zipper. Judson hired Gideon Sundback in 1901, and by 1913 he was head designer at the Fastener Manufacturing and Machine Company, newly relocated to Meadville, Pennsylvania after a stop in Hoboken, New Jersey. Sundback’s design called for rows of identical teeth with cups on the underside and nibs on the upper, set on fabric tapes. A slide with a Y-shaped channel bent the tapes to open the gap between teeth, allowing the cups to nest on the nibs and mesh the teeth together strongly.

Sundback’s design had significant advantages over any of Judson’s attempts. First, it worked, and it was reliable enough to start quickly making inroads into fashionable apparel beyond its initial marketing toward more utilitarian products like tobacco pouches. Secondly, and perhaps more importantly, Sundback invented machinery that could make hundreds of feet of the fasteners in a day. This gave the invention an economy of scale that none of Judson’s fasteners could ever have achieved.

Putting Some Teeth into It

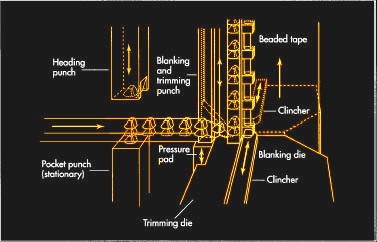

The machinery that Sundback invented to make his “Separable Fastener” has been much improved since the early 1900s, but the current process still looks similar, at least for metal zippers. Stringers, which are the fabric tapes with teeth attached, are formed in a continuous process by a multi-step punching and crimping machine. For metal stringers, a coil of flat metal is fed into a punch and die to form hollow scoops. The strip is then punched again to form a Y-shape around the scoop and cut it free from the web. The legs of the Y straddle the edge of the fabric tape, and a set of dies then crimps the legs to the tape. A modern zipper machine can make stringers at a rate of 2000 teeth per minute.

Plastic zippers are common these days, too, and manufacturing methods vary by zipper style. One method has the fabric tapes squeezed between the halves of a die while teeth are injection molded around the tape to form two parallel stringers. A sprue connected the stringers by the teeth breaks free after molding, and the completed stringers are assembled later.

Zippers have come a long way since Sundback’s first successful design, with manufacturing improvements that have eliminated many of the manual operations once required. Specialized zippers have made it from the depths of the oceans to the surface of the Moon, and chances are pretty good that if we ever get to Mars, one way or another, zippers will go with us.

IIRC, the word “Zipper” was the brand name of rubber overshoe that first used the mechanism.

It later became part of the generic lexicon such as Kleenex, and Xerox…

And now we have Velcro. ;-)

And zippers made out of coiled plastic strips. (yecch!)

Those are the ‘self repairing’ type. If a loop cracks the zipper still works and won’t pop open. Mess up one tooth on the ‘classic’ type of zipper and it won’t stay closed.

I found the video pretty annoyzing.

It also seems pretty wastefull to first make a continous zipper and then strip 20% of the brass of again.

It wastes material and machine time.

Try as I might, I couldn’t find a decent video focusing on the business end of the machine. There a “How It’s Made” that tries to get in close, but it just didn’t show the detail I was hoping for.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MgnIC9dCkFA

The only other video I found was an episode of “Mr. Roger’s Neighborhood” where he showed how zippers were made in the 1970s using Picture Picture. It was pretty fascinating to see how little the machinery has changed, and it was a blast to watch old Fred again.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=axKdVb_HRe0

There is one for making plastic zippers. It’s in German language but the video itself should be mostly self explanatory.

http://www.wdrmaus.de/filme/sachgeschichten/reissverschluss.php5

Im not sure though, whether the link works from outside of Germany.

The simpler machine probably runs faster than a machine that can switch between teeth and endstops. Plus, if there is a quality control failure, just skip that section instead of failing the whole zipper.

Annoyzing: noun. a portmanteau of the words annoying and amazing.

ex. “I found the video pretty annoyzing.”

Worth mentioning the YKK group — a Japanese firm that has crazy zipper market share. Seriously find a zipper near you, it probably says YKK.

And yet it’s not like YKK zippers are so wonderful, I had them fail numerous times.

I think it depends on the model zipper the garment vendor selected. You bought cheap clothes with cheap YKK zippers.

Both my carhart’s have insanely robust YKK zippers that haven’t failed in years of use.

i destroy stock zippers (YKK, all of them) on most things after 2-5 years. i’m hard on zippers, like on backpacks i will use a single zipper pull to support 20 lbs of weight.

and for 3.5 years i have been in the habit of replacing failed zippers, also using YKK nylon zippers, but using the next size up. i haven’t had an after-market zipper fail yet. so, this is weak anecdotal evidence for encee’s point. YKK makes such a variety, i think manufacturers just combine under-sizing and using a cheap kind that is cheaper than what you see at fabric/hobby stores (but the “skirt zippers” that are so ubiquitous are *garbage*). in 5 years if hackaday runs the same story again i’ll report how they’ve aged after a real test. :)

Don’t neglect the possibility that many zippers labeled YKK are in fact, copies.

A person who can replace zippers aught to be able to attach some rings to support loads ;-)

How are they holding up afrer 6 years?

Nope, not cheap clothes, sorry to ruin your attempt at dismissing a truth.

They used to be pretty good too. Times have changed.

They are both durable, and both cheap: YKK has a whole range of product, from very cheap, to very sturdy: as zakqwy mentioned, they have a huge market share and must answer with a complete range.

Not sure why people are so desperate to defend that company. You got shares in it or something?

What has a thousand teeth and bites wieners? … a zipper.

I had heard rumor that there is a city in China that specializes in zippers. Has anyone else heard that?

China ha a tendency to put related industries together.

And there have a lot of zippers to be made.

About 8 minutses into this vido some info about a zipper foctory to the local community.

The video is not interesting enough to see as a whole. Mostly propaganda.

tube.com/watch?v=6sNzrTbBDk8

RandyKC: Look here 28°10′02″N 120°28′42″E

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Qiaotou,_Yongjia_County

City in china makes 80 percent of worlds zippers

I think a “real hack” is to repair a zipper.

Carefully removing damaged teeth and replacing them with teeth removed from one end where they won’t be missed.

Uh, normally you just un-stitch the whole zipper and replace that.

You can measure continuity of the entire zipper length (if metal teeth) and detect when it has been broken open. I use this concept to trigger an alarm and camera in my luggage for when baggage handlers attempt to open the zipper with a pen.

i like this :)

I think you should be able to print the zipper track :)

https://youtu.be/Eefc9jLq1mE

I wonder how many man hours are saved each day by zippers. Could easily be in the hundreds of thousands if I had to take a SWAG.

I remember when they had a stamping of a profile of squirrel holding the obligatory nut. That was Squirrel Nut Zippers, later a retro swing band.

on swiss roads where two lanes merge there often is a sign “reissverschluss” (zip), to encourage drivers to merge like a zip would.

thing is, people don’t know how that’s supposed to work…

You are saying the Swiss are dumb as a rock?

it’s not just the Swiss…in many countries the majority of drivers fail at understanding (and mainly executing) how this is supposed to work, causing stop&go traffic on line merges where it should be nice and fluent.

They need to design a better sign. And maybe put some ads in magazines and the like, so people get the idea. Maybe use the idea of riffling cards as a motif.

Even then, there’s always some dick who has to get there 15 milliseconds sooner, who messes up the whole traffic system for everybody, ultimately including themselves.

I can’t imagine drivers anywhere not understand two lane of traffic merging into a single lane. Then again so many drivers appear to have found their driving license in Cracker Jacks box.