The principle is well understood: use a motor in reverse and you get a generator. Using this bit of knowledge back in 2001 is what kick-started [Ted Yapo]’s Hackaday Prize entry. At the time, [Ted] was searching for a small flashlight for astronomy, but didn’t like dealing with dead batteries. He quickly cobbled together a makeshift solution out of some supercapacitors and a servo-as-a-generator, hacked for continuous rotation.

A testament to the supercapacitors, 17 years later it’s still going strong – leading [Ted] to document the project and also improve it. The original circuit was as simple as a servo, protection diode, some supercapacitors, and a LED with accompanying resistor; but now greater things are afoot.

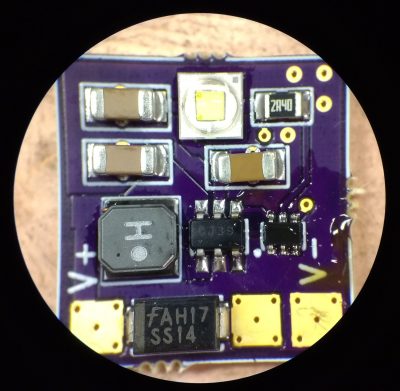

A DC-DC boost converter enables constant power through the LED, regardless of the capacitor voltage. This is achieved by connecting the feedback pin of an MCP1624 switcher to an INA199 current-shunt monitor. The MCP1624 kicks in at 0.65V and stays active down to 0.35V. This is all possible due to the supercapacitors, which happily keep increasing current as voltage drops – all the way to 0.35V. Batteries are less ideal in this situation, as their internal resistance increases as voltage drops, as well as increasing with age.

When testing the new design, [Ted] found that the gears on his servos kept stripping when he was using them to charge capacitors. Though at first he attributed it to the fact that the gears were plastic, he realized that his original prototype from 2001 had been plastic as well. Eventually, he discovered the cause: modern supercapacitors are too good! The ones he’d been using in 2001 were significantly less advanced and had a much higher ESR, limiting the charging current. The only solution is to use metal gear servos

Want to read more about boost converter design? We have the pros and cons of microcontrollers for boost converters, or this neat Nixie driver for USB power.

If you power that LED with a couple alkaline cells, it will run for years of occasional use, if you turn it off when you’re done. I gather the problem was leaving it turned on in a toolbox.

A battery-powered circuit with auto shutoff seems like the obvious solution.

You’d think so, huh. Reality it that parasitic current will usually drain those even if they’re never turned on. I have a couple headlamps i bought, tested once, absolutely turned off, and put them in a drawer. Less than two years later they’re dead. It happens.

And a decade of use is hard to argue with, that’s pretty good.

This still have an application where reliability an indefinite shelf life is relevant, like in a life raft. Might even be used on a wind up VHF emergency radio or beacon?

I have had two 2xAA sized ‘LED Lenser’ flashlights drain their batteries down so far in a few months that the batteries leaked. They were both turned off and stored in a toolbox.

The first one was terminal, I had to use a drift to punch the batteries out, the second I caught in time and was able to repair the damage.

Won’t be buying a third one……

Parasitic current from what? If the headlamp is one of those ones where you click once to turn it on and click again to turn it off, perhaps it is simply a momentary switch with a pushbutton power circuit… But with an actual switch in the current path? I don’t see any reason why the batteries should drain any faster than when sitting on the shelf.

I don’t see paraitic current being the problem here at all. It’s more like conventional batteries degrade pretty fast over time because of internal chemical processes. The solution here could be to use lithium batteries which are available in conventional form factors like AA or AAA and offer 15-20 years of storage time when not being used.

That’s why Rocket asked a question. Gravity – I’d trade your battery depletion knowledge for a crash course in humanity, as mutual respect is seemingly beyond your personal experience.

i don’t really know what others meant by parasitic current but my experience is that alkaline batteries only last a couple years sitting on the shelf. oh, the disappointing things we learn as adults when the decades start flying by. did you know my kids are already in school?!!

Awesome – EDLCs are very cool for short/medium-term energy storage, it’s just a shame that their leakage current is high enough to be a problem over the course of days-months.

Using a boost converter is a good idea – I’ve been using some of Pololu’s cheap ones with supercapacitors and having pretty decent success since they go down to 0.5V – but a specially-designed converter probably works better.

Too funny, he improved it and my first thought was more electronics and stuff, more stuff to go wrong, and sure enough, the new version broke, Not in a way I anticipated, but still…

17 years ago., a hackaday. Wow, time flies!

Yeah, that was a confusing sentence. Hackaday is 15 this year (which is like a billion in Internet Years!) but Ted started the project before we existed.

If anyone is trying to generate reasonable amounts of power in a smallish space, stepper motors are the way to go. Quite often 30-45vac even with surprisingly low rpm and plenty of current. Enough that you’ll feel the jolt in your forearms.

yeah i’m not an expert on motors but when the headline said servo, i was stunned. i don’t know any advantage to servos for this purpose except that you’re guaranteed to strip the gears. they’re not even particularly cheap unless you’ve recently given up on a model airplane hobby or something.

What a servo is, is a very cheap (I’m assuming he didn’t use expensive servos) DC motor and gear train, already put together. Removing the feedback pot and grinding off the rotation stop makes it a gearmotor, or a geared generator, that’s small, cheap, and easy.

An intermediate project ( have no energy harvesting, nor optimizations ) using solar energy http://www.absolutelyautomation.com/articles/2016/02/19/reusing-solar-rechargeable-keychain-flashlight . Future project, make some similar with a small windup flashlight from the “D” store!

“The only solution is to use metal gear servos” Uh, no. If the problem is that the series resistance of the supercapacitors is too low, another solution would be adding a series resistor. Duh.

Beware of the words “the only solution” when commenting on Hackaday.

To be fair “the only solution” was the phrase used by the HaD writer, not [Ted] whose project this is.

My thoughts exactly … but I guess he wanted to eat the newly found additional cake and still have it – energy saved is energy produced.

If you are not part of the solution, you are part of the precipitate.