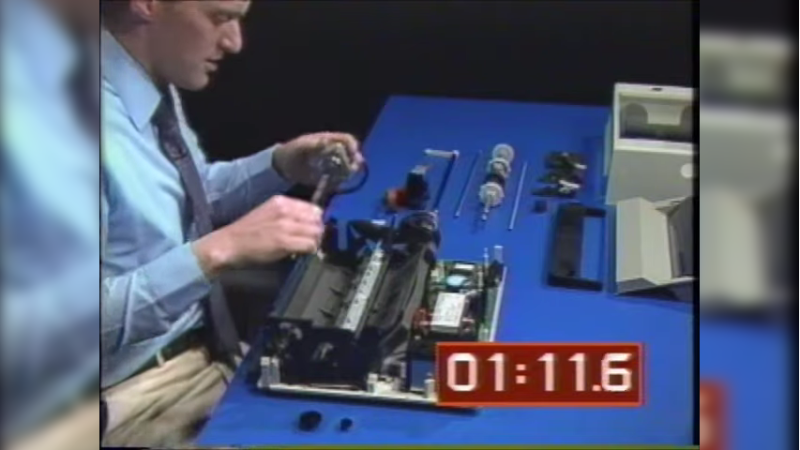

To get its engineers thinking about design for assembly back in the 1980s, Westinghouse made a video about a product optimized for assembly: the IBM Proprinter. The technology may be dated, but the film presents a great look at how companies designed not only for manufacturing, but also for ease of assembly.

It’s not clear whether Westinghouse and IBM collaborated on the project, but given the inside knowledge of the dot-matrix printer’s assembly, it seems like they did. The first few minutes are occupied by an unidentified Westinghouse executive talking about design for assembly in general terms, and how it impacts the bottom line. Skip ahead to 3:41 if talking suits aren’t your thing.

Once the engineer gets going on the printer, though, things get really interesting. The printer’s guts are laid out before him, ready to be assembled. What’s notably absent from the table are tools — the Proprinter was so well designed that the only tool needed is a pair of human hands. And they don’t have to be particularly dexterous hands, either — the design favors motions that are straight down, letting gravity assist the assembly process and preventing assemblers from the need to contort their bodies. Almost everything is held in place by compliant mechanisms built into the plastic parts. There are a few gems in the film, like the plastic lead screw that drives the printhead, obviating the need to string a fussy timing belt, or the unique roller that twists to lock onto a long shaft, rather than having to be pushed to its center.

We found this film which we’ve placed below the break to be very instructive, and the fact that a device as complex as a printer can be assembled in just a few minutes without picking up a single tool is pretty illustrative of the power of designing for assembly. Slick designs that can’t be manufactured at scale are all too common in this age of powerful design tools and desktop manufacturing, so these lessons from the past might be worth relearning.

Thanks to [The Free Thinker] for the tip.

I wish this came out as a DIY kit!

Can anyone comment on the reliability of this printer once it entered the market? I’m curious of all that simplification had any impact on it’s long term function.

That power supply massive.

I worked as a repair tech at a Computerland store back in 1981. Sold and repaired lots of IBM gear. This video brought back lots of memories! They actually were a great little printer, and as easy to repair as that video would indicate. I really miss that kind of design.

But no screws, only clips? I personally find it horrible with these clips in plastic cases that with a chance of 50% break when you try to open the case. Sure easy to manufacture, but difficult to open?

We had Proprinter XL at home (132characters) got it as remainder as my Dad worked for IBM. We had it from 1987-1992. I had it at college, and never had a problem with it. The floppy controller on IBM XT failed, but Proprinter XL ran and ran and ran. Eventually we got an Epson FX to replace it.

I owned a ProPrinter for a number of years an never had a failure. It was extremely capable for a dot matrix printer although mine wasn’t an XL model and was limited by width of the carriage to standard sized (8.5×11) paper feed. The best thing about it in those days was the fact that it was recognized by nearly every piece of printing software available at the time, with no need for additional drivers. Some things are better left unchallenged for reliability and cost effectiveness and this is one that makes the list. These days of late, I have to wonder why I ever thought a color laserjet was an improvement. And usually those days are when I have to reorder 4 new toner cartridges for a single printer.

Reminds me of the IBM PS / 2 Models 30 / 50 / 55SX / `70

You didn’t need to open the case for most repairs. To replace floppy drive: lift the blue tab at the bottom of the FDD, slide FDD out, insert ned one. Same with HDD and some other components.

I called them the Lego computer.

Just think of how easy modern computers could be. Of course people are approaching in the other direction with SBCs and adding onto that.

I loved the IBM ProPrinter! Rugged, simple, reliable. And that front slot for single-sheet feed was pure genius.

Ahh, yes, the metal plattent that made the printer a horrible ear splitting noise while it printed. Great printer as long as you don’t have to be anywhere near it.

The old desktop IBM’s and HP’s from the mid-to-late 90’s were very easy, lots of molded spring tabs, relatively few fasteners that needed tools once you got the case open.

Many of the quasi-busisness HP desktops are still like that, They are popular in my extended family because they are so readily available at the big boxes. But they are so encumbered with bloatware when one goes bad I refuse to touch it for fear of breaking it on the software side by changing a driver or something.

I’ve always been impressed by the desktop Mac’s. Very few tools need in there, either.

The bloatware on most computers is awful. I always reinstall (with the included OEM key) and let Windows install the drivers without the garbo software

I remember this printer design very well, but not for the right reasons!

We had very bad experiences with Proprinter II’s at my elementary school. The parts of plastic that held everything together got brittle over the years and would break, some of them had to put back together with hot melt glue, and the front panels and buttons were always failing for some reason. Wish I had one, they made some pretty awesome noises in my opinion.

Owen Wilson is doing a great job assembling this printer. You can see that this is one of his early work as he watches the director several times to check if he’s doing right.

Way to go Owen!

It’s worth remembering that designing for assembly is very different to designing for maintenance. Just because something can go together easily, it doesn’t mean it can come apart easily.

Cars are an excellent example of this.

Very true. Snapping plastic latches come to mind.

The start of the throw-away mentality. All those plastic clips will go brittle, the plastic springs he talks about will go hard, the acres of white plastic will go yellow. But I get it – it makes it cheaper.

I can appreciate the clever aspects of the design for manufacture, but this is negated by the lack of thought gone into maintainability. I’d like to see the video of him taking it apart again.

But never mind, when it breaks just buy another easily-made one, they are cheap. Probably cheaper than gettiing someone like me to carefully find and undo-without-breaking all those plastic clips.

All fine until some idiot (me) tries to take stuff like this apart in 30/40 years time. How hard can I pull this/prise it apart/twist it, until it snaps like an arthritic hip. Bomb disposal is less stressful.

If you suspect any plastic is going to be brittle, warming it up first helps, prop it on the radiator/vent for a bit when the heat’s on, or go over it with a hair dryer.

Doesn’t have to be brittle. CPU plastic fan bracket had really thin clips. Broke really easy in removal. Good thing it came with two.

A little cheating for show. A large number of those “parts” were assemblies that required multiple parts themselves. Build time includes those sub-assemblies as well.

I’ve disassembled a lot of printers since Proprinters were manufactured (to salvage parts) and all of them have a large number of screws, springs and usually a belt. Perhaps this design method was not as revolutionary as they would have you believe.

VCRs back in the 1980s had Service positions.

Remove the cover, a few screws, and the circuit boards could be swung into a position that allowed the tech to monitor/repair the tape path.

I was the product designer who designed the helical screw that drove the print head back and forth. The edict was “no pulleys, no screws, no springs.” The printer was assembled in a special built factory originally in Charlotte, NC. Various parts were sourced as sub-assemblies. IBM had a “drop test” at the time and as I recall the printer would be dropped and then plugged in to see if it worked. If you did want to take the case off, as I recall there were slots into which you’ve put the blade of a screwdriver to pry back the large connectors on the base. At the time, many companies were moving manufacturing to Singapore and the labor in Singapore was no longer “cheap” (although it was very skilled). IBM’s goal was to make the product in the US and sell their own printer rather than an OEM. John Drejza was the visionary for this product. He was a very talented and thoughtful boss.

The beginning of this article suggested that Westinghouse was somehow in partnership with IBM on this printer. It was not.

At 8:49 in the video (elapsed time 2:59.0 with the engineer) : “IBM allows the customer to take care of this.” I just picked myself up off the floor. “Allows”! Too funny.

These days “allows” beings up thoughts of changing out a battery or a screen on our phones, or its software etc etc. Getting Linux to run on a PS3 or some other device known to be theoretically able to do so. You know. This contrast to this sort of corp-speak (for “we ain’t gonna do it .. save a penny and make the purchaser do the dirty work”) is humorous.

I wonder how many customers were begging to be “allowed” to install the printer ribbon themselves. Not that the act in of itself matters, so much as the characterization. Ahh, the many uses of “allows”. Sometimes meaning grant permission, other times meaning user assembly required.