Up here in the Northern Hemisphere, mosquitoes and other flying pests are the last thing on anyone’s mind right now. The only bug that’s hindering gatherings at the moment goes by the name of COVID-19, but even if we weren’t social distancing, insects simply aren’t a concern at this time of year. So it’s little surprise that these months are often the best time to find a great deal on gadgets designed to deter or outright obliterate airborne insects.

Case in point, I was able to pick up this “Bug Zapper LED Bulb” at the big-box hardware store for just a few bucks. This one is sold by PIC Corporation, though some press release surfing shows the company merely took over distribution of the device in 2017. Before then it was known as the Zapplight, and was the sort of thing you might see advertised on TV if you were still awake at 3 AM. It appears there are several exceptionally similar products on the market as well, which are likely to be the same internally.

In all fairness, it’s a pretty clever idea. Traditional zappers are fairly large, and need to be hoisted up somewhere next to an electrical outlet. But if you could shrink one down to the size of a light bulb, you could easily dot them around the porch using the existing sockets and wiring. Extra points if you can also figure out a way to make it work as a real bulb when the bugs aren’t out. Obviously the resulting chimera won’t excel at either task, but there’s certainly something to be said for the convenience of it.

Let’s take a look inside one of these electrifying illuminators and see how they’ve managed to squeeze two very different devices into one socket-friendly package.

Let there Be Light

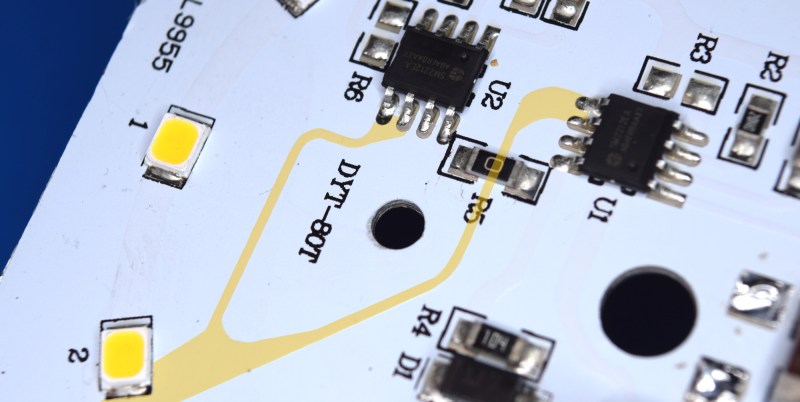

Under the frosted plastic dome on the front of the zapper bulb is…well, what you’d expect to find inside of a cheap LED bulb. A few years ago this kind of thing might be novel, but we’ve seen it all before.

With just fourteen run-of-the-mill diodes, the light produced from this bulb isn’t particularly impressive. According to the manual it’s putting out 600 lumens, which would put it just slightly north of what you’d expect from an old school 40 W incandescent bulb. Being a relatively low-power array there’s no external heatsink on the bulb, the aluminum backing of the PCB seems enough to keep things cool.

With just fourteen run-of-the-mill diodes, the light produced from this bulb isn’t particularly impressive. According to the manual it’s putting out 600 lumens, which would put it just slightly north of what you’d expect from an old school 40 W incandescent bulb. Being a relatively low-power array there’s no external heatsink on the bulb, the aluminum backing of the PCB seems enough to keep things cool.

The limited light output is made worse by the fact that all the diodes point forward, making this more of a bad spotlight than anything. Arguably that might be desirable outside, especially if this was placed in a high light socket and you wanted to throw a beam down on a porch or deck. But in that case it would have been nice if they actually indicated that by giving the bulb a more distinct spotlight shape.

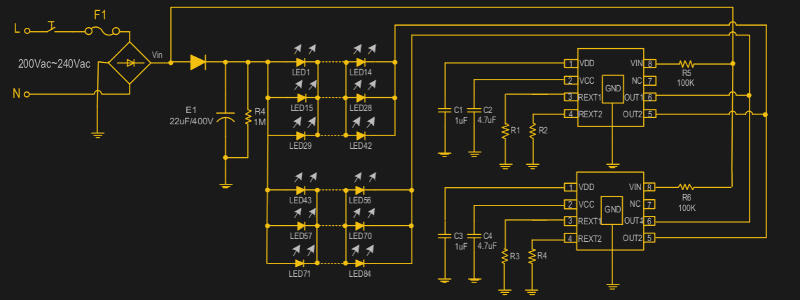

Beyond the LEDs, the only components of any note are the dual SM2212EA driver ICs. I couldn’t find an English datasheet for these, but a rough online translation of the PDF provided the highlights: they run on 90 to 240 VAC, offer a two-stage brightness control, and have built in thermal shutdown. But the fact that there are two of them seemed odd, and on closer inspection, the way they were connected didn’t seem to make any sense.

The answer comes from the datasheet, which explains on one of the final pages that if the power requirements are so high that a single SM2212EA goes into thermal overload, you can simply duplicate the single chip application and tie their outputs together to run them in parallel. Each chip has two output pins because one is the full brightness pin that comes on first, and the second is the reduced current pin that dims the LEDs after the power switch has been flicked on and off.

That makes sense, except for one problem: the LEDs on this product don’t actually dim. When you flick the switch on the first time the light and zapper functions are both on, and when you flip it again, the LEDs go off completely while the zapper stays on. So what’s going on?

While the datasheet isn’t very clear, it seems that the resistor connected to pin 4 of the SM2212EA is used to set the amount of current the secondary dimming pin will pass. But a close look at the PCB shows that this resistor is missing for both chips (pads R3 and R6 on the silkscreen, R2 and R4 on diagram), so the dimming function is essentially disabled. If you were so inclined you should be able to drop a pair of 200 ohm resistors across those pads to turn it back on, but you’d lose the ability to use the zapper without the light on.

Ride the Lightning

Below the LED PCB and on the other side of a little plastic bulkhead, we find the electrified elements that do the actual zapping of bugs. They appear preposterously overbuilt for this application, which makes me think more thought was given to the aesthetics of the shiny chrome grid than its bug-busting properties. It seems like a tighter grid of smaller diameter wires would have been more effective, but wouldn’t have looked nearly as nice sitting on the shelf or during the late-night TV infomercial.

On the plus side they’re attached to the high-voltage PCB with nothing more exotic than some M3 screws, so they can be easily removed for potential modification or reuse. At the center of the grid are four UV LEDs which serve as the “bait” to bring the bugs in. Now as we’ve learned from the COVID pandemic, not all UV LEDs are created equal, and these are probably only good for attracting bugs. (Oh wait.)

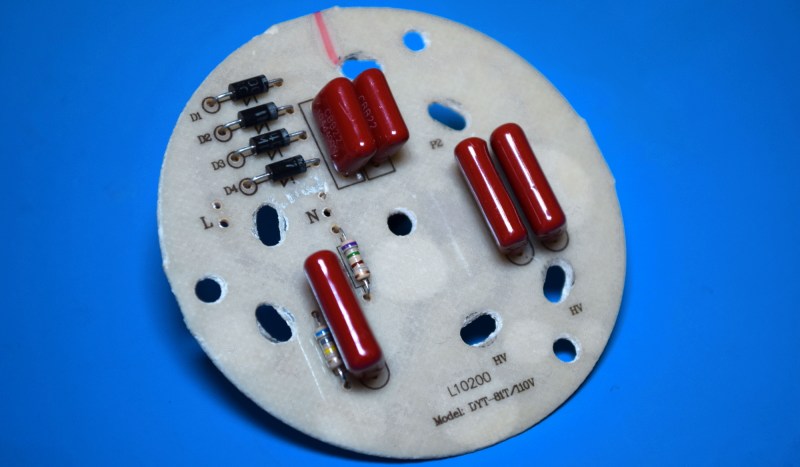

Taking a look at the back of the HV PCB, we can see just how simple of an arrangement we’re dealing with. There’s no transformer involved, just a basic voltage multiplier circuit using four pairs of diodes and capacitors. That gives a maximum potential of a little under 500 VDC when running at 120 VAC here in the US, which as far as I can tell, is exceptionally poor for a bug zapper. A quick perusal of Amazon shows even the relatively cheap models are advertising grid voltages of 3 to 4 kV.

For the record, I didn’t lose count. The fifth capacitor off to the left side with the pair of diodes is being used to provide the power for the UV LEDs on the other side of the board, and doesn’t appear to be connected to the HV side of things.

Master of None

So on the top we have a pretty ho-hum LED bulb, and on the bottom, a photogenic but ultimately anemic bug zapper. Through a pair of legitimately hacked dimmer ICs, the user has the ability to turn off the LEDs, but the high voltage zapper is live whenever the power is supplied. Though to be fair, it’s hard to imagine a scenario in which somebody would buy one of these things but not want to use the zapper function.

So on the top we have a pretty ho-hum LED bulb, and on the bottom, a photogenic but ultimately anemic bug zapper. Through a pair of legitimately hacked dimmer ICs, the user has the ability to turn off the LEDs, but the high voltage zapper is live whenever the power is supplied. Though to be fair, it’s hard to imagine a scenario in which somebody would buy one of these things but not want to use the zapper function.

I can’t say that it’s poorly built, in fact, I was somewhat impressed by how competently everything seemed to be put together. But functionally, I’d be hesitant to pay the full $20 USD MRSP. If you’ve got a bug problem, you’d be better served with a real zapper that has a bigger UV light source (often a small fluorescent bulb) and a more powerful HV source. That said, if you see one of these drifting around the clearance rack for a buck or two, it’s probably worth salvaging its internal components to power your high voltage adventures.

Bug zappers are at best ineffective at mosquito control, and at worst extremely damaging to local insect populations.

Insect die-off is not a good thing, despite your feelings regarding being un-assailed while spending minimal time outside.

From a technology standpoint this light is novel, but from a usability viewpoint they suck, and from an ecological standpoint they are terrible on many levels.

While it’s true that zappers are wholly ineffective against biting insects (which do not navigate by light sources), there are some valid use cases.

Consider my garden, where the majority of pest damage has come from cutworms and cabbage loopers. Both are variants of moth larvae, and adult moths are notoriously attracted to lights. A zapper offers effective, pesticide-free population reduction.

We don’t ask that the unit control mosquito populations, though: that’s accomplished with ovitraps and drainage.

I got a few of those smaller bug zappers that seem to be all over Wish. I bought 1 to try and it got quite a few mosquitos and other bugs that got inside the house, so I bought some more. The one in the garage is the champ, when I leave garage door open working on car or yard all the bugs flock to the ceiling light. Then that gets switched off and they all go to those almost UV leds and get zapped. My son has a bad reaction to mosquito bites so was ready to try anything. The ones I got are about wall plate size with a color plastic guard over the HV rails. When you go to clean them take it out of the socket and use a wire brush to get the bugs out of it, gives a nice spark and the leds flash for a second. The parts count looks like nothing but maybe the drivers for the leds and a tiny HV source, haven’t had one break yet so havent taken one apart yet.

So you have a poorly done porch light that’s built to attract and semi-permanently accumulate electrocuted biota overhead. Just the thing to greet your guests.

Yah, but you could rig a servo to tap them out if it’s an unsolicited canvasser.

Changed my mind, vibration motor would probably do it nicely… bzzzt bzzzt *shower of dead insects*

I’ve bought several of these over the years and they work pretty good indoors for the mosquitoes that get inside. Unfortunately, all have suffered from degrading LED output. After a year or so (they’re on only at nite) the led were just barely visible. I ended up replacing just the leds with ones from Sparkfun. Maybe they are being overdriven?

Hmm I just feed the birds and have a nice little habitat for the lizards near the trashcan. I love watching the warblers do their work and sweep the yard at the micro level haha. They are so tiny they do not bend the grass yet they can space out their little squad and comb my backyard in an hour or so.

I honestly don’t have anything against bug zappers. If that is the way you want/need to go then do it to it. Where I currently live they actually spray to manage the bitey insect population, so it lessens the need for one but if you live out in the sticks they definitely can get rid of some pests. I would suggest building a bat box or two to keep a population around to help out at night :)

Just use a blue-white bulb pointed up near the ceiling and have the light at the entrance of a muffin fan suction bug trap. Light is in the high velocity intake, chamber, filter,and fan. No bugs indoors no loud noises just a computer fan. The light is within inches of the ceiling above kitchen cabinets. They circle around the light getting closer till caught in the event horizon, a ring of death surrounding the light.

There some of this type on the market, too weak of a fan etc. till they get up to commercial size. With good filtering they can be used in food plants, the zappers have big catch pans and the bugs just sit there. My bulb might last forever as it is in constant air cooling. It’s replaceable, the fan is line powered and lasts for years. They market a mesh to put on a window fan and use on the patio for breeze and effective skeeter control, as large amounts of carbon dioxide aren’t floating around you.

Disgusting technology!

The fact that it’s an insect doesn’t mean you can kill it by burning alive via electricity. If you really need to kill it, do it using a swatter. The result being the same doesn’t mean the way you do it does not matter. This is a way of respect to that animal and to it’s creator. Even in war there is a difference between beating your enemy mercilessly and beating him/her in a honorable way.

Creator? No. I don’t believe in any god.

You do understand that this is at least as quick as death by swatter and has nearly binary action, right? With a swatter you can mangle an insect, but leave it alive, not so much with high voltage contact across an object the size of an insect. The insect either avoids contact and is fine, or touches the grid and immediately dies. That being said, please feel free to further enlighten us as to your humane bug-smashing techniques and paraphernalia.

Both opponents must have similar weapons to call it “honorable”. Get a used 0.2 mm acupuncture needle and settle the dispute with a swordfight.

Perfect answer

I found the best solution to be bats. Our county farm sells cost-effective bat houses.

Some really odd comments here. Thanks for the teardown, agreed that it does sound like a good idea, but not effective enough for the cash. Hopefully they improve as I don’t want to buy a proper bug zapper!

To understand how some of the products that emanate from the workshops of China come together, you have to know the process that produces them.

There are some HUGE websites in China, all in the Chinese language, on which you can design products of your desire. After complete you credentials, you click Enter, or 进入,

A day or two later proposals and prices start arriving in your mail box. The Chinee manufacturers are amazing design optimisers and they offer their suggestions and pricing starting, usually, at 500 or 1000 pieces.

Let me give you an example of what we do.

We consume 555 ic’s by the truck load but there are two real pain-in-the-butt connections. From memory these are Pin 2 linked to Pin 6 and Pin 4 linked to Pin 8. So our 555 supplier simply connects these together internally and the pain-in-the-butt PCB connections are no more. We started ordering in 500 piece quantities, although now our orders are in the 5,000 range.