The name Rube Goldberg has long been synonymous with any overly-built contraption played for laughs that solves a simple problem through complicated means. But it might surprise you to learn that the man himself was not an engineer or inventor by trade — at least, not for long. Rube’s father was adamant that he become an engineer and so he got himself an engineering degree and a job with the city. Rube lasted six months engineering San Francisco’s sewer systems before quitting to pursue his true passion: cartooning.

Rube’s most famous cartoons — the contraptions that quickly became his legacy — were a tongue-in-cheek critique meant to satirize the tendency of technology to complicate our lives in its quest to simplify them. Interestingly, a few other countries have their own version of Rube Goldberg. In the UK it’s Heath Robinson, and in Denmark it’s Robert Storm Petersen, aka Storm P.

Rube Goldberg was a living legend who loved to poke fun at everything happening in the world around him. He became a household name early in his cartooning career, and was soon famous enough to endorse everything from cough drops to cigarettes. By 1931, Rube’s name was in the Merriam-Webster dictionary, his legacy forever cemented as the inventor of complicated machinery designed to perform simple tasks. As one historian put it, Rube’s influence on culture is hard to overstate.

Engineer of His Own Future

Reuben Garrett Lucius Goldberg was born July 4th, 1883 to Max and Hannah Goldberg in San Francisco, California. He started tracing cartoons in the newspaper at the age of four and kept drawing throughout his childhood. Rube never had any formal drawing lessons, though he did take a few lessons from a sign painter around age 11.

When Rube announced his intent to become a famous cartoonist, his family was horrified. Rube’s father, a policeman and fire commissioner, had worked hard to to provide a good life for his family after emigrating from Germany. He equated artists with beggars, and wanted Rube to be an engineer.

Though Rube still dreamed of becoming a famous cartoonist, he got a mining engineering degree from UC Berkeley in 1904. He then took a job with the city of San Francisco as a water and sewers engineer. Rube hated the job so much that he quit after six months, and took a job at the San Francisco Chronicle for one third the pay. Rube started out at the bottom, emptying wastebaskets, sweeping the floors, and filing photographs. But he still drew every chance he got, and was eventually hired by the San Francisco Bulletin to be their sports cartoonist.

Crazy Contraptions with Explanatory Captions

In 1906, a powerful and deadly earthquake shook San Francisco. Faced with his own mortality, Rube realized that if he wanted to be nationally famous, he’d have to go where the action was — New York City. The following year, Rube moved across the country by train in the hopes of getting hired by a nationally-syndicated newspaper. Just when he was ready to sell his father’s diamond ring for a train ticket back home, he was hired by the New York Evening Mail.

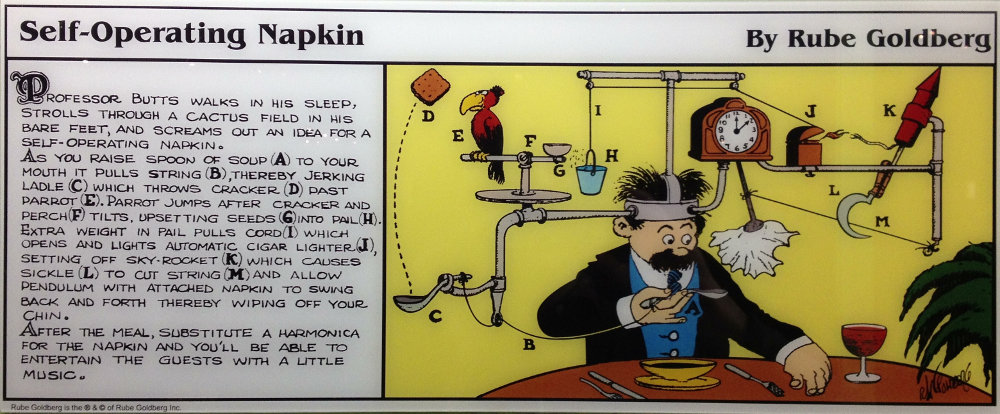

As we all know, Rube Goldberg is most famous for his contraption cartoons that employ ridiculous chain reactions to solve every day problems. These intricate machines were all inventions of Rube’s alter ego Professor Lucifer Gorgonzola Butts, who was loosely based on one of Rube’s engineering professors at Berkeley. He drew the first one of these around 1912 and shot to fame and fortune soon after. Rube spent many hours perfecting his cartoons and would spend upwards of 60 hours drawing a single cartoon.

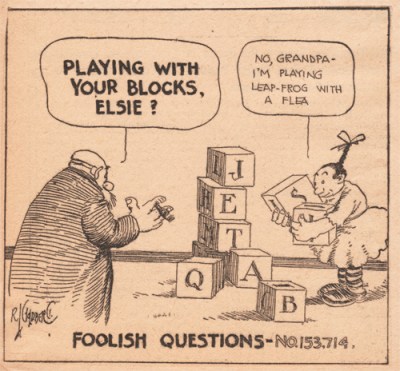

Rube drew all kinds of cartoons about sports, politics, and current events. Soon after getting hired at the New York Evening Mail, Rube started his first nationally-syndicated cartoon called “Foolish Questions”. These single-panel cartoons depicted one person asking another a question where the answer is painfully obvious. But as the saying goes, ask a foolish question, and you’ll get a foolish answer — the retort is usually an oddly-specific oddball answer.

Between 1905 and 1938, Rube drew more than 60 different cartoon series including “Foolish Questions”, “The Inventions of Professor Lucifer Gorgonzola Butts”, and “Mike and Ike (They Look Alike)”, which likely spawned the candy of the same name.

Rube drew so many different strips and panels throughout his career that historians have a hard time cataloguing it all. In 1930, Rube’s inventions came to life on the silver screen in the movie Soup to Nuts, which introduced the world to the slapstick comedy of the Three Stooges.

Still Relevant, Still a Household Name

Rube Goldberg had an amazing 72-year career as a cartoonist. Throughout his career, he drew an estimated 50,000 cartoons, both political and otherwise.

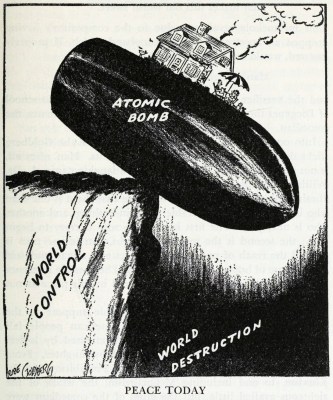

Rube won the 1948 Pulitzer Prize for Editorial Cartooning for a single-frame political cartoon called “Peace Today” that depicts a nuclear family balanced on a precipice dividing world domination from total destruction of same. He never stopped making art and became a sculptor at age 80. He died in 1970 at the age of 87.

Although Rube may never have built any of his own creations, his imagination continues to inspire people to invent their own wild ways of solving problems and make them come to life. All across America, schools hold contraption-building competitions every year in his honor, often with a required minimum number of actions.

We’ve seen plenty of Rube Goldberg-inspired builds over the years. Here’s one that systematically opens a bottle of beer, and another that uses a CNC router to scrape the stuf out of Oreos. Have you ever built a Rube Goldberg machine? Let us know in the comments!

In Spain we had “The inventions of Prf. Franz of Copenhaguen”, also known as “The great inventions of the TBO”, clearly “inspired” in the comics from Rube Goldberg.

https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Los_grandes_inventos_del_TBO (in spanish)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GvnEBX9aedY

Rube Goldberg mouse trap in old Tom and Jerry episode

They also included one of those in the recent Tom and Jerry movie!

ROFL, cats should equal a mouse free house… there is a device sold at hardware stores branded “Tin Cat” , studying the device, it’s easy to copy….

We need Tom’s design for the banana activated windshield wipers…. the auto wipers we’ve got activate when rain hits the right place, they don’t come on for bug splatter or bird poop.

They used to have a board game called mousetrap, it was basically a rube Goldberg machine.

It was also funny, in watching the cartoon, that my grandparents had a old washing machine in the basement, and their light switches were the old pushbutton style.

It seems like Goldberg’s cartoons cemented the idea in the public consciousness of the “eccentric professor with complex inventions,” as demonstrated by Professor Brainard in the Absent-Minded Professor and Doc Brown in Back to the Future.

Don’t forget “The nutty Professor” with Jerry Lewis ! (that’s actually how many people picture chemists…)

Wilf Lunn on TV in the UK, Caractacus Potts in Chitty-Chitty-Bang-Bang.

If the women don’t find you handsome, they should at least find you handy.

There’s a difference between useles inventions, and inventions that are useful but badly implemented.

Rube Goldberg was skewering design. Very roundabout ways to accomplish something. Something is wrong if you can see some complicated method to do something, but not see the simplest way.

I remember a book review in Electronics Illustrated over fifty years ago. The title was something like “101 Useful household gadgets”. But the reviewer pointed out that a four transistor alarm for the garage could be replaced by a pingpong ball on some string, to indicate where to stop your car.

Rube Goldberg was complicating the simple! to make a point.

Wallace & Gromit seemed to be a mix, capable projects and then roundabout design.

For many years, I kept a picture of Rube in my desk. I still have it. I wrote across the bottom, ” My Hero”.

Good thing we have a tradition of newspapers and magazines; a home for budding cartoonists to grow.

In The Goonies, they have a Rube Goldberg methid of opening the door. And some of the pirate booby traps towarrs the end are like that.

Too bad he died in 1970, years before the film came out. He’d be giggling at the movie

Well maybe it’s a good thing he didn’t stay an engineer. Looking at his cartoons, a window to his engineering mindset, can you imagine what the sewers in San Francisco would have looked like!?

Can’t imagine pictures but words like cool and awesome come to mind stubbornly.

Maybe he saw the existing sewers that he had to work with, and that made him think “how on Earth did they come up with this junk?”

The musical group “OK Go” has created some really incredible Goldberg machines for their music videos.

https://www.youtube.com/results?search_query=ok+go+music+goldberg

On the wall of my workshop, I got a print of the Shadok’s cartoon that says :

“pourquoi faire simple quand on peut faire compliqué ?”

“Why do simple when it can be complicated”

https://www.google.com/search?q=shadok+pourquoi+faire+simple+quand+on+peut+faire+compliqu%C3%A9&client=firefox-b-e&source=lnms&tbm=isch&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjMwt_RupPvAhXK3YUKHXgBBHoQ_AUoAXoECB4QAw&biw=1908&bih=942

This reminds me of The incredible Machine, a DOS game we used to play.

It’s still around and playable with DOSbox.

My son and I spent many hours together playing that game.

Contraption Maker from the same people.

https://store.steampowered.com/app/241240/Contraption_Maker/

I had that on a floppy disk. Loved that game.

Interestingly, a few other countries have their own version of Heath Robinson. In the US it’s Rube Goldberg….

Rube was truly an engineer’s engineer. The level of detail and complexity of his designs are worthy of study. Not everyone can go to the depths and levels of complexity to solve simple tasks like him. If he turned his mind to solving string theory we would probably have a unified theory by now!

It feels to me like today’s Rube Goldberg is Randall Munroe of xkcd