When someone talks about “The Grid,” as in “dropping off the grid” or “the grid is down,” we tend to think in terms of the electromagnetic aspects of the infrastructure of modern life. The mind’s eye sees The Grid as the network of wires that moves electricity from power plants to homes and businesses, or the wires, optical cables, and wireless links that form the web of data lines that have stitched the world together informatically.

The Grid isn’t just about power and data, though. A huge portion of the infrastructure of the developed world is devoted to the simple but vital task of moving liquid fuels from one place to another as efficiently and safely as possible. This fuel distribution network, comprised of pipelines, railways, and tanker trucks, is very much part of The Grid, even if it goes largely unseen and unnoticed. At least until something major happens to shift attention to it, like the recent Colonial Pipeline cyberattack.

A Series of Tubes

This story actually started a week before the pipeline attack while I was filling up some gas jugs at the local filling station. There was a tanker truck parked in the lot, dispensing gasoline and diesel into the buried storage tanks through big hoses. Any driver is likely to have witnessed a scene like this before without giving it a second thought, as I had many times before. But it struck me this time that I had no idea where that tanker truck had filled up before heading out on the morning rounds. Where I live in North Idaho, the nearest seaport — a logical place for gasoline and other fuels to arrive by tanker from refineries located in other parts of North America — is a six-hour drive away. Would a truck driver really be asked to drive that far to pick up and then deliver fuel?

As it turns out, the tanker trucks that we all see topping off the tanks at gas stations are only the very last link in the petroleum transport network, and tanker trucks in general play only a small role in the fuel distribution system. The network is divided into two main functions: getting crude petroleum from where it’s produced to where it can be processed into finished products, and getting the finished products to the customers. While surface transportation, especially oil tankers, play an outsized role in moving crude oil around, the finished products network is dominated by pipelines.

In the United States, there are close to 200,000 miles (322,000 km) of oil pipelines, the bulk of which is dedicated to moving finished products from refineries to consumers. Some of these stretch vast distances, like the 5,500 miles (8,900 km) that the Colonial Pipeline covers on its way from the refineries of Texas through the major cities of the southeast and Eastern seaboard through to its terminus outside of New York City in Linden, New Jersey. The twin pipelines, with one devoted mostly to moving gasoline and a smaller one used for other products, like diesel and jet fuel, move a total of three million barrels (126,000,000 gallons or 477,000,000 liters) of product every day.

Pipelines move oceans of petroleum products around every day, and criss-cross the country in an intricate web of infrastructure. And yet, almost all of this vast network is invisible, buried safely below ground for the majority of its length, surfacing only occasionally at pumping stations, control points, and tank farms. Pipeline construction itself is a fascinating subject; a pipeline is much more than just a buried pipe, and an immense amount of effort and engineering goes into building one.

Mix and Mingle

Once a finished products pipeline is built and tested, it begins the non-stop work for which it was designed. Like trucking companies, shipping lines, and railways, pipeline companies are what’s known as common carriers, which means they have to accept shipments from anyone who meets their published specifications. They don’t generally own the product that’s being shipped, but rather contract with the products’ owners to move it from one place to another. This means there are almost always products from more than one refiner in a pipeline at any time, queued up along the length of the pipe.

In addition to a mix of product owners, each shipper will likely have a variety of products in the pipe at any one time. The most common example is the different grades of gasoline, which in the United States basically means different octane ratings and varying amounts of ethanol. These all travel in the pipeline in sequence, immense slugs of each product nestled up against each other. There will necessarily be some mixing of products that occur in transit, resulting in what’s known as intermix zones. Product from intermix zones needs to be treated differently from the “clean” product in the middle of the bolus. In the case where different grades of gasoline are intermixed, the receiving tank farm generally puts the mixed product into the storage tank for the lower of the two grades, on the theory that it’s better to sell a slightly higher grade of fuel than is being advertised. When different products, like gasoline and diesel, get intermixed, the receiving facility has to segregate the intermixed products and send the unmarketable cocktail back to the refinery for reprocessing.

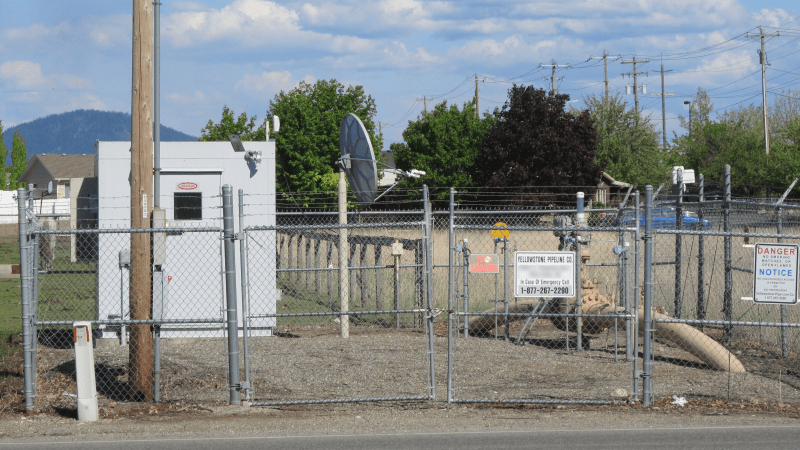

In either case, the state of the product in transit and the overall health of the pipeline are monitored by a far-flung array of sensors. Determination of which product is at which point in the pipeline is normally the business of specific gravity sensors, which continually sample the density of the product as it moves along in the pipe. Pipelines also routinely monitor pressure, temperature, and flow rate along their length, as well looking for leaks and any sign of intrusion into any of their above-ground facilities. These sensors, along with actuators on valves that control the flow, are remotely controlled by the pipeline operators through a SCADA, or supervisory control and data acquisition, network.

Down on the Farm

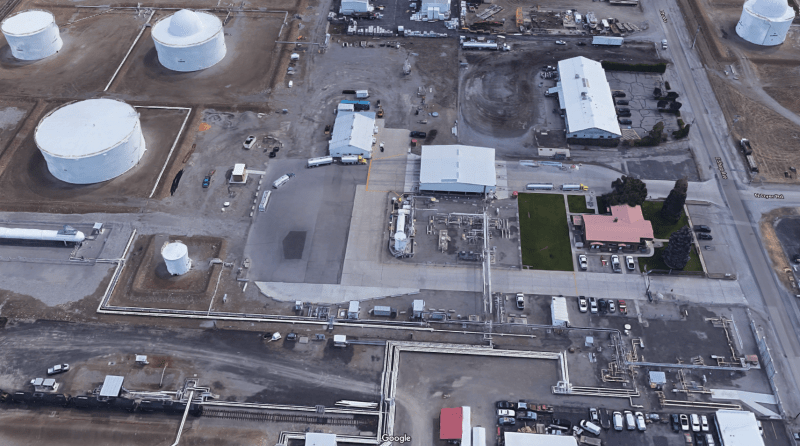

At the terminus of most pipelines, and sometimes at points along the way, are located one of their more recognizable above-ground features: the tanks farms. Also known as oil terminals and varying in size from just a few small storage tanks to dozens or hundreds of towering structures, tank farms serve as a rest stop for finished petroleum products on their journey from refinery to filling station. Tank farms can also serve as junctions between two or more independent pipelines; for example, in my area, finished products are shipped from refineries in Utah in a pipeline that terminates in Spokane, Washington. The tank farm there serves the entire eastern Washington and Idaho Panhandle region; another pipeline starts at the Spokane terminal and extends east over the Rocky Mountains to an oil terminal in Thompson Falls, Montana, which serves the entire western region of that state.

Each oil terminal will have the pumping gear and valves needed to divert the pipeline’s flow into different storage areas, so that the incoming products from different manufacturers can be segregated before being shipped to customers. Different tanks are available to store the different grades of fuels, too, as well as for the intermix products that need to be shipped back to the refinery. Most oil terminals do very little in the way of manufacturing; products generally arrive there ready to be sold to consumers. Some terminals do perform a limited amount of blending, though, and some may even add ingredients such as ethanol as seasonal needs dictate.

As efficient as pipelines are at moving products around, it’s important to note that they’re not universal. There are vast stretches of North America that aren’t serviced by any pipelines, particularly in the western areas of the United States where population density can’t support the investment needed. The northeast US also lacks many pipelines, but for the exact opposite reason — population density makes it hard to get right-of-way to build pipelines. There, other modes of transportation have to suffice; in New England, for instance, the oil terminals in New Jersey fill up barges with finished products, including the all-important home heating oil, which then head up Long Island Sound to fill the tanks of oil terminals in cities all along the coast.

On the Road Again

Finished products generally don’t spend much time in the tank farms of an oil terminal. From the pipeline operator’s perspective, storage space in an oil terminal is a limited resource, and clearing out tanks to make room for new products coming up the pipeline is critically important. From the products’ owners viewpoint, they can’t make any money until the product is delivered to a retailer. So, it’s in everyone’s best interest to have a streamlined and efficient process for getting products shipped out of the terminal.

To that end, most terminals are designed to get tanker trucks filled and on the road again as quickly and safely as possible. Tanker trucks are filled from the bottom, with the vapor phase of the volatile liquids recovered for recycling. Each tanker is usually divided into multiple compartments, so that different grades of gasoline can be loaded — in the United States, diesel is never carried in the same tanker as gasoline, so an entirely different tanker is used to deliver diesel to gas stations.

The total time that finished petroleum products spend in transit from refinery to customer varies, but is primarily a function of how long it spends in the various pipelines along the way. In the case of the Colonial Pipeline, under normal circumstances it takes about five days for a product to make it from Houston to New York. So in most cases, thanks to the efficiency of the fuel distribution network, the fuel you’re filling up with today was probably refined no more than a week or so ago, and has spent most of its short life in the pipe.

My wife and I walk through a local tank farm as part of our daily walk (a public road cuts it in two) and it was fascinating to watch as they went through some major upgrades last winter (pre covid).

Oh really? Do tell. I’d love to hear about special equipment and old v new equipment.

The road that passes through is called Terminal Road, and there is one tank farm on the “north side” and another on the south. Adjacent to the south terminal is the pipeline complex, where they apparently replaced a lot of line and valves.

We typically walk through the area about 10pm, but for some time they were still working. Of course, we could not get that close, but it was fun seeing the daily progress.

The fume burners are also cool to see at night.

At the bottom is some railroad tracks, so everyone one in a while you’ll catch a NS train passing by, and you far fairly close.

Is the Colonial pipeline the ownership successor to the Big Inch and Little Inch pipeline projects installed during WWII, to prevent German uboats from sinking all our then-tanker-ship-based distribution network? That was a huge project, running a pipeline from Texas to NJ, and they put it together in less than a year. My mom remembers seeing tankers burning off the coastline of NJ after being torpedoed, when she was very young.

Suncor has a huge refinery near where I live, that a highway and a bike path go through. It’s interesting to see; there’s a hobby refinery (for lack of a better term) at one end, an older section of the refinery that used to be a separate, competing unit in the middle, and the big facility at the other end, that just got finished with about a billion dollars of upgrades, plus two tank farms, one for holding refinery products going into pipelines, and the other for the airport a few miles away.

Before the big upgrade, the larger section of the refinery had at least a dozen flareoff chimneys. Now they’re down to two, and they burn a lot less material than the old ones used to, so they’ve gotten more efficient.

The big inch turned in TEPPCO, (Texas Eastern Products Pipeline Co), and is now owned by EPCO (Enterprise).

I never knew Uboats prowled the coast of NJ in the early 40’s. Horrifying.

My grandfather grew up in Corpus Christi and remembered the town shutting off lights at night due to Uboats prowling of the coast. I’m not sure if it was just a precaution but I do know it was taking very serious.

There are a few sunken U-boats you could dive on up and down the east coast as well as stories of a few in the Gulf of Mexico.

the idea of intermix zones is BLOWING my mind! got any resources so I can read more about intermixing and the challenges in it?

Likewise, I can’t mix fluids in pipes in Factorio but in the real world they do it all the time? I’d have at least thought there’d be large steel capsules or drums to keep separation but I guess it isn’t worth the cost.

Some pipelines use ‘pigs’ to separate different fluids, or even the same fluid provided by different customers. They also are useful for cleaning the walls of the pipeline to avoid further contamination. They have some really cool smart pigs that can do inspections as they move. It is more common to see pigs in oil pipelines than refined fluid pipelines though. It is just cheaper/easier to send the refined fluids in a ‘smart’ order to minimize transmix, and then just send the junk back to the refinery and have them separate it out again because refined fluids don’t gunk up the pipelines as much as crude.

It was a plot point in one of the Bond movies/books; they sent an agent down an oil pipe in a specially crafted pig with a seat and re-breather to smuggle them in or out of Soviet Union.

The Living Daylights, with Timothy Dalton. The people-smuggling pipeline was really cool! The tricked-out winterised Aston Martin was also excellent. The 1980s Afghan politics in the film were… intriguing.

Me too! I’m guessing it costs money to ship it back and separate it, so if I had an device that would run in intermix, would they pay me to take it? Or could it at least be had very cheap? It seems odd that no one is using it.

With the demand on it being so low and interrupting the normal flow of sending it back to the refinery, it would probably be expensive to get. Burning transmix efficiently would also be a challenge. The whole point on refining crude is that the derivatives behave so differently. Multifuel engines do exist, but they are either incredibly complex, or incredible inefficient/dirty. I had a M35 that could run off about just about anything you poured into it (leaded, unleaded, kerosene, diesel, avgas, even fuel oil and diluted used motor oil), but people at the EPA would have a stroke if an engine like that were commonplace…

Very cool video. Thanks.

Between the Dutch island of Ameland and the mainland, there used to be a 15 km (9mi) long milk pipeline. The milk wasn’t sent through continuously, but there were inflatable rubber balls before and after each “packet” with cleaning passes.

The milk took on the sea water temperature and was too warm occasionally, so after 18 years the pipeline was discontinued. When glass fiber cables were installed to the island, they reused this pipeline which had a considerable cost saving.

I am wondering why mixed pipelines don’t use this rubber ball technology to separate fuels.

The city of Bruges in Belgum has a 3.2km (2mi) beer pipeline from the city centre brewery to a bottling plant on the outskirts of the city.

You see these types of separators (called ‘pigs’) in crude oil pipelines due to the build up of unwanted materials on the pipe. The byproduct is that they can also be used to separate out different fluids and different customer’s product. With refined materials that flow relatively clean, the added complexity and cost isn’t worth the process of pigging each batch. If the material is managed and sent in a smart order (trying to minimize switches between gasoline and diesel/heating oil mainly) the amount of transmix is lower than you’d think. And the transmix isn’t waste, it is just sent back to the refinery where it can be separated out again, just like the crude was originally.

I’d imagine the intermix isn’t that huge of an issue either, they probably aren’t sending frequently changing gas/diesel product. Probably something more like where going to be pumping 89octane gas down the pipeline for the next 12 hours. all the terminals along the pipeline probably just draw off their order, metered at the exit points of the pipeline much like water to your house. Then for another 12 hours switch it to 93contane, terminals pull off their metered product, then diesel, then whatever other products they send down it. That way rather than a ton of intermix zones you only have a few. Intermix of gasoline product is probably no issue at all. Regular and Premium fuels are already mixed at the terminal, or some gas stations that only have two product tanks and intermix regular and premium to make the mid grade(s) with a metering valve in the pump itself.

May not even be an issue of mixing the different octanes, if they just ship 89 octane down the pipleline and then at the terminals or as it is pumped into the delivery truck add in the octane boosters/detergents that get shipped in by truck/rail. Bascally the same products you can buy off the shelf at your local auto parts store to add to your gas. A tanker full of octane booster might be able to treat millions of gallons of fuel, so might not even be worth it to ship different grades down the pipeline. Probably your different things going down the pipeline are a base gasoline that is treated with different boosters/detergents at the terminal, diesel, keresone, jet fuel,

Correct. Octane & additives are added at the terminal. All of the different gas “brands” in an area get their gas from the same location. The only difference is their specific additives are loaded while filling the tanker trucks.

There’s a large tank farm in Norcross, GA (33.91012, -84.27085) that has a rail line running through it. Years ago one side of the tank farm caught fire and there were photographs taken by people on the train.

I had talked to someone who worked there at some point, and back then they shipped 87, 89, and 93 octane generic gas through the line, and the vendors added their own additive packages when the tanker trucks were loaded. They also shipped Amoco Ultimate Premium as it’s own slug, along with diesel. This was before slugs were shipped in “smart order”, so they did run a pig between each fuel grade and type.

At one point during WWII there were multiple 8cm pipes going from Dungeness in the UK across the channel, to Rouen, and from there all the way past Eindhoven, pumping petrol.

Do you mean Operation Pluto?

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operation_Pluto

As a fuel hauler I can tell you gasoline and diesel are hauled in the same tanker. Just a different compartment.

Was going to jump in here to say the same thing, but you beat me to it. Wasn’t uncommon to have rookie drivers accidently dump gas into a diesel tank or vice versa at a station, and the transport company have to pump out the entire tank and take it back to the refinery for processing. You didn’t get to make that mistake too many times before you were out job hunting again.

Year’s ago I drove for Arrow transportation. The pipeline from Montana to Spokane Washington was down for upgrades. Hauled 10200 gallons of gas per trip. Pasco Washington to Spokane Washington. 22 Semi trucks hauling for two months.

That was actually really interesting. It was crazy to watch a huge pipe with 1/2in thick steel walls flop down into a trench like a garden hose. Human engineering is amazing. The section about multiple products sharing the pipe at one time was also surprising.

Reminds me of a pipeline going through a rainforest and the natives using it as a kind of road.

If it’s just one week from refinery to my tank, why does the price at the pump stay high for months and months after any interruption of service?

Same reason as when crude goes up 10%, pump prices go up 10%, despite the cost of crude being only a fraction of the pump price, but when it comes down 10%, they only drop 5%…

Pipeline is its own tech but i thought that they would put a slug of water between products. then any tank farm switching happens during the water part. In a tank you get oil/gasoline and water but they naturally separate while sitting in the tank. Can anyone verify what I was told?

I do know that for very viscous fluids they add a diluent to make it less viscous so it can be more efficiently pumped. Sometimes its nitrogen.

Oil/Gas pipelines do not want water in the line. It can create problems during cold weather with freezing in valve bodies and create corrosion problems.

…~ grid composed of … “tanker trailers…”

And tankers like the Exxon Valdez.

Damn Nazi U-Boats were infesting the waters from the Gulf Coast all the way up to the North Sea. In addition to attacks on our coast, it was hell for the merchant fleets that were destroyed, often unarmed, in the passage to and from England. Terrible waste of lives, and truly heroic sailors.

https://uboat.net/maps/us_east_coast.htm

https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/head-here/2014/04/25/aa5c8202-c3d5-11e3-b195-dd0c1174052c_story.html

A recent Tom Hanks movie offers a taste of what it was like, albeit a ‘Hollywood’ version.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greyhound_(film)

This story about pipelines reminds me of a sewer pipeline that my dad worked on many years ago. The Lake Oswego Interceptor Sewer (https://www.ci.oswego.or.us/archive/lois/overview.htm) is designed to “float” ~20′ below the surface and is anchored to the lake bed by steel cables. The most interesting part of this is that (unlike pressurized fuel pipelines) it actually has to maintain a grade to keep the effluent moving.

My summer job in 1994 was as a welder’s helper and roustabout on natural gas pipelines in western Wyoming. Miles and miles of three-inch steel pipe, welded together from 25 foot sections. (Oddly, 3″ = 7.62 cm, and 25′ = 7.62 m. Not sure how that works out.) Natural gas runs in different pipes from liquid petroleum derivatives, of course, but I’ve watched pipeline news more closely ever since.

A foot is 12 inch, or 4*3″. So 25ft is 100*3″.

The large pumps and how the pressure is created to move the product is interesting…. The Ransomware attack on Colonial illustrates how precarious society is with just-in-time delivery and vertical integration. Global markeplaces in many industries means that financial efficiencies have eliminated diverse or redundant production. Be it gasoline or rare-earth metals, to steel or microchip production. Upset the balance and things go sideways pretty quickly.

On a wildly different tangent, a tour of a US football stadium offered a view of pipes moving fluids around the stadium. When asked if the piping labeled beer was full or empty, the tour guides changed the subject.