Al and I were talking about the IBM 9020 FAA Air Traffic Control computer system on the podcast. It’s a strange machine, made up of a bunch of IBM System 360 mainframes connected together to a common memory unit, with all sorts of custom peripherals to support keeping track of airplanes in the sky. Absolutely go read the in-depth article on that machine if it sparks your curiosity.

It got me thinking about how strange computers were in the early days, and how boringly similar they’ve all become. Just looking at the word sizes of old machines is a great example. Over the last, say, 40 years, things that do computing have had 4, 8, 16, 32, or even 64-bit words. You noticed the powers-of-two trend going on here, right? Basically starting with the lowly Intel 4004, it’s been round numbers ever since.

I wasn’t there, but it gives you the feeling that each computer is a unique, almost hand-crafted machine. Some must have made their odd architectural choices to suit particular functions, others because some designer had a clever idea. I’m not a computer historian, but I’m sure that the word lengths must tell a number of interesting stories.

On the whole, though, it gives the impression of a time when each computer was it’s own unique machine, before the convergence of everything to roughly the same architectural ideas. A much more hackery time, for lack of a better word. We still see echoes of this in the people who make their own “retro” computers these days, either virtually, on a breadboard, or emulated in the fabric of an FPGA. It’s not just nostalgia, though, but a return to a time when there was more creative freedom: a time before 64 bits took over.

Iirc, IBM owned 8 bit architecture and would sue every and anybody using it without the extremely expensive license they offered.

No they didn’t.

Ok, my healty daily dosis of desinformation :) I want to believe Scully!

Shurely you meant 9-bit? (EBCDIC)

That’s why Intel never made an 8 bit cpu? Oh wait, the 8008 and 8080 existed.

The “factors of six” thing is almost certainly due to pre-ASCII character representation by 6 bits. That would be 64 characters, “enough for anybody”, and plenty for control characters, puctuation, numbers and upper case (lower case is just a distraction).

The CDC CYBER 74, on which I took my assembly language programming course, had 60 bit words and 6 bit character codes, IIRC. ASCII conversion for Teletype I/O took place in an auxillary “concentrator” called a Tempo (TEMPO Computers, 1971).

6-bit bytes were a thing in the pioneer and first generation world of computing because of the frequent choice of 6-bit BCD (Binary Coded Decimal) as the character code. BCD is an adaptation of the older 12-bit Hollerith code used by electric accounting machines. In its basic form, Hollerith code encodes a character as a combination of a zone and digit punch in a single card column. BCD code reduces the bits required to 6 by expressing the zone as a 2-bit binary value and the digit as a 4-bit binary value.

Because BCD was often the chosen character encoding, machine word size was frequently a factor of 6. For example, IBM’s 700 line of scientific computers, the 701, 704, 709, 7090, and so on had a word size of 36-bits. Magnetic tape for these machines used 7 tracks, 6 for BCD encoded characters with the 7th track serving as a parity bit.

Of course, you can also account for widths like 15 and 27 as well as factors of six, if you consider the popularity of octal representation back in the pre-unix-epoch mists. Otoh, a lot of the earlier MSI chips supporter three or six functional units, so maybe octal was popular because of the tendency to groups of three bits. Hard to pin down the causality from 50+ years on, but these things seem interrelated.

The character set was formalized as US FIELDATA. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fieldata

I think it was due to the choose of 36 bits in the original Von Newman paper.

There are many other word sizes…

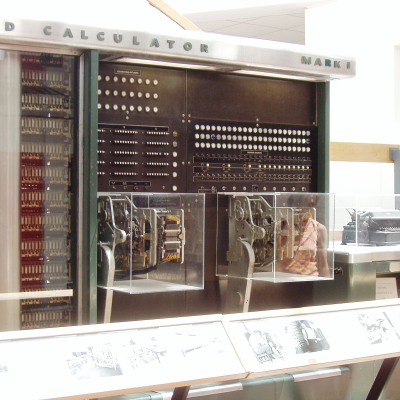

The commercially and academically (Tony Hoare’s seminal Algol60 compiler) important Elliott 803/903 has 39 bit words. See one running at TNMoC, and discuss the schematics with helpers there (my kind of museum). The 39 bit word contained two 18-bit instructions plus a strange modifier bit.

The ICL1900 series had 24-bit words (containing 4 bytes of 6 bits).

Motorola MC14500 was a 1-bit machine.

And I won’t include bit slice processors, because that would be cheating :)

The “weird” word sizes were a combination of the extreme cost of discrete circuits including odd implementation tricks, plus a “pre-Cambrian” style explosion of inventions, most of which have died out.

Odd implementation tricks include relatively complex logic gates based around magnetic core components – cheaper than Ge transistors!

https://www.ibm.com/docs/en/zos/2.5.0?topic=guide-understanding-31-bit-addressing

Word lengths in the early days was actually pretty simple. Usually, the instruction also encoded memory addresses along with the instruction. Registers were really expensive, so outside of an accumulator and program counter and maybe or maybe not a stack pointer, everything was done as (usually) between the accumulator and some value in a memory location. So on a PDP-8, a typical instruction had 4 bits for the instruction and 8 bits for a memory location in a 256 word page. With instructions to jump between pages, you could address more memory. The other, more oddball word lengths you mention were similar, but with different constraints. The military guidance computers were often constrained by the desired precision of the integer instructions. They needed enough bits to get the resolution needed. To meet timing constraints, it was better to use a longer word with one memory fetch than to break it up into multiple ones.

With the IBM 360, that changed. It broke the link between the instructions and memory addresses. This allowed variable length instructions, allowing for more compact programs. Not to mention, more instructions could be encoded and more complicated instructions could be used, like the POLY instruction in Vaxen. By the time of the 360 tubes were out, transistors were in and the budget for active elements was relaxed. Using even powers of two simplified a lot of things in the architecture and removed potential bottlenecks in performance. Not to mention, it allowed the killing off of coding in octal which was popular on those 12, 18 and 36 bit machines…

And that also explains why it wasn’t until well into the 1970s that a byte was reliably 8 bits instead of, say 6.

3 bits for instruction, one for indirect, one for page zero vs current page, 7 bits for word within that page.

You are correct. It is what I get for relying on memories from the ’70s.

It was fun, but there are times I regret them…

Yes, that’s what I figured. Basically fixed length instructions and single address modes on accumulator architectures made instruction lengths variable, even though a typical instruction format would be:

[OpCode][EA Bits like Indirect or current page][B-modifiers/Index Regs][Ea offset].

The re-introduction of RISC with their fixed-length instructions reintroduced a number of the same considerations, where the address offset could only handle a small part of the address range (ARM32 being one of the strangest).

What RISC brought to the table was lots of general purpose registers. Otherwise it does look a lot like those early accumulator-based architectures.

Through the oddities of the Internet I recently did a shallow dive into LINC, which I maintain was the first personal computer. It gives good insight into the design decisions of those computers and how everything revolved around the amount of memory in the system.

The LINC is interesting. I think the first confirmed “personal” computer was a pdp-8 at EMS Studios, London in the late 1960s. EMS produced some early mono synths like the VCS-3 and a famous Vocoder (ELO’s “Mr Blue Sky”), but their commercial side was mostly a front to fund their massive synth and the pdp-8, based compositional language that could drive it.

https://120years.net/musys-and-mouse-audio-synthesis-language-peter-grogono-untied-kingdom-1965/

Of course it’s always debatable as to ‘first home computer’ but Peter Zinovieff had a PDP/8S at his home studio in the mid-late 60s, there’s some footage and interview in the excellent BBC documentary ‘What the future sounded like’ on Youtube.

I’m guessing that is the same Peter Grogono who wrote a Pascal programming textbook which I used at Uni. Interesting, I had no idea of his background.

LINC was the first kind of mass produced lab computer. One user at a time, graphics display. keyboard, printer, mass storage and input devices. Now it wasn’t a home computer, but it had every attribute of what we think of as a personal computer.

That cost as much as a nice house.

Hackaday needs a different font, or I’m gonna keep reading the first sentence of this article as “A[rtificial ]I[ntelligence] and I were …”

You can call me Al

I can call you Betty

And Betty, when you call me, you can call me Al-l-l-l-l ! Very clever Paui Slimon!

How come no mention of variable length words? I believe some of the Symbolics Lisp Machines had this, maybe other Lisp Machines, like TI Explorer?

It’s not just you. I did the exact same thing!

+1

+100

Seriously, guys, it’s the 21st century ! There are more fonts available ! And for a site that prides itself on hacking, is it really that hard to change the default font for a website ? Would you tolerate such ambiguity in an IDE while you are writing code ? How about on a component spec sheet ?

+1 or is that +l (lower case L)

Sooner or later someone will think that HAD has LLM called Williams.

When I was at Northwestern University in the 1980s, The main computing was done on a CDC 6600, with a 60-bit word. If I remember correctly, that could store 10 text characters, or 15 decimal digits (maybe).

By the time I graduated, it was considered extremely out of date, especially as it ran a custom operating system. This is because NU had a champion chest program that depended on that OS. When those researchers left for warmer climes, It was swiftly replaced with VAX/VMS.

Your mention of odd numbering schemes and “retro” implentations reminded me of that U. Penn project some years back to put ENIAC on a chip:

https://www.seas.upenn.edu/~jan/eniacproj.html

This effort included its base 10 number system.

Even today, a little weirdness persists. While most Forth processors were 16 or 32 bit, the MuP21 and its derivatives were 21-bit processors (with 20-bit wide external memory interfaces! the 21st bit only existed in the internal stacks) and its descendants, the GreenArrays chips, are matrices of parallel 18-bit processors with tiny amounts of memory; and all of their instructions are 5 bits wide. Chuck Moore was a staunch advocate of word-addressed machines before he retired from CPU design.

cleaver idea? cleaver?

It’s very divisive.

Your mention of odd numbering schemes and “retro” implentations reminded me of that U. Penn project some years back to put ENIAC on a chip:

https://www.seas.upenn.edu/~jan/eniacproj.html

This effort included its base 10 number system.

The GE 600 series addressed memory as 36-bit words. Bytes could be extracted from those words, and the bytes were either 6 or 9 bits. Characters were 6 bits.

Reminds me one of the projects with did in 2007 maybe. We needed to quickly dump quite a LOT of mainframe data out of DBase into whatever client was thinking he will be doing (mostly naive stats/tallies btw – I saw the final proposal) from its internal EBCDIC into 32-bit mumbo-jumbo of colossal proportions representing the tip of the iceberg. Fun, fun, fun. Once we went through maybe three iterations the project was cancelled, right after we stabilized the solution enough to produce good usable results.

Burroughs / Unisys A-Series were 52 bits. 48 were user addressable, the others were used to tag what the word was used for (data, Double Precision markers, Software Control Word, Indirect Reference, etc. Only programs that were compiled with Espol or NEWP could alter the tags. It’s a very cool stack machine architecture on top of that.

Mention of the IBM hardware (360 & 3083, etc) reminds me that they continue to support 31 bit computing.

Before LSI every bit required more circuitry either in the form of whatever Gates you were using or bit slice chips (well, okay, in that case the bitwith of the slice multiples). So if you had a contract you were bidding on you wanted to be the low bidder. You’d look and see what the precision requirements were for math and say okay to represent the numbers we’re going to have to deal with at the sufficient precision. I need 11 bits. So you built your computer with 11 bits and saved money over somebody who would say use 16. Getting the whole CPU on the chip of course changes that which means you now have to make your design fit on that chip and it’s a no-brainer to just use it.

That doesn’t explain the big general purpose computers of course, but there’s a lot of little Beckman and perkin Elmer machines and things like that that have really strange bit widths and that’s why. Same for address bits. If your code needed a certain amount of address space, you built that many address bits and you didn’t put any more in.

Also, don’t forget that the early computers were mostly for mathematical calculations, so each decimal number required around 3 bits per decimal digit to get the desired precision. For example, to have 9 bits of decimal precision required around 30 bits.

Isn’t that because they pretty much WERE?

Also it was an era when wire was cheap, transistors were expensive, and a computer was such a massive investment (and such a rare unicorn) that weird builds for specific reasons carried no real penalty compared to the added cost of, for example, just making the words 8 bit instead of 6.

Hell, sometimes a change like that would involve having to reinforce the floor of your building to accommodate the thing, or get the electric company to bring in a bigger power feed much like the problems data centres face today.

An IBM 2260 display terminal like the one shown in the title picture sold on eBay a few years ago, IIRC it was listed at 3000 USD and I think sold for that. Given its rarity I thought that was a fair and acceptable value. The unit was missing the bezel around the screen but otherwise complete. This terminal was as dumb as dumb could be and needed an external controller to generate the characters. I once had an acoustic delay line unit from the 2260’s controller as a kid, but pulled it apart to look inside. As I did with other bits of dead 360 my dad brought home for us kids to do so. Wish I could go back and kick myself!

The 2260 terminal I mentioned:

https://www.reddit.com/r/vintagecomputing/comments/10ey0gn/vintage_1960s_ibm_2260_terminal_i_recently/

Elliot check out the NOAA National Weather Service national mainframe working certainly in 1987 as I was a high school intern at the NWS office at the airport where I lived for 6 months and eventually learned the language for inputting the observations and bring able to pull up CTR Astroids level graphics of weather radar and other observations from anywhere on the system. Every NWS office had one and I think it was called AFOS?

It was super cool for a young nerd. This was also before they had the automated voice radio transmissions about current and forecasted weather over the radios that they still operate and I would go in when I was working and actually give the announcement in my voice announcing the station identifier the time etc there was a little script written on the wall and then you just fill in the observations at the moment that apply and the current forecast.

No it’s all automatic and most of the guys working there were Vietnam veterans at the time for some reason as I think they were doing that in Vietnam and had preferential employment as well as the education and skill set necessary and they would report their observations up to the air traffic control tower who would then enter it into their mainframe but they were separate mainframes. Part of our job was to actually go out on the field and make sure and do the maintenance on all of the measurement devices like the device that measured how far you can see how much rain the wind speed and direction etc….

We were also connected to the new system of emergency Management that used big microwave transmitters and receivers that were nailed on to the walls of the airport.

It was really interesting for a junior in high school as I was a part of a special program for gifted students that allowed us to pick internships at different locations and one of these was with the National weather service and I was really interested in that one and actually did it twice. I also worked at the PBS station in my community and both was a camera operator for live events and did black and white headshots for the various personalities.

They then let me loose with my camera and color slide film that they would drop in in between shows with a timer showing when the next show would start as they didn’t have advertisement etc

They were landscape photos basically really nice pretty landscape photos from my part of the country.

I live in a different country now and and the duel which may be ending depending on a certain bill they really shouldn’t do a blanket bill but they should like do a country by country analysis as to whether or not that country is or has an adverse ideology to the United States that would be more enlightened and modern then a blanket prohibition imagine that Albert Einstein was the first dual National and he was a dual Swiss US national because he required that they let him keep his Swiss nationality before he would take the US citizenship. I swear neutral country how can there be a loyalty issue?