It’s time for Computex, and that means [Linus] has dropped something. I don’t know what, but he’s dropped something. It’s a meme or something at this point. What were the highlights? Asus announced Project Precog, a laptop with two screens. Yes, a touchscreen keyboard. It’s the 2018 version of the IBM Transnote or whatever that Microsoft thing was called. Why is it called Project Precog? Because AI or whatever. Unimaginative marketing is terrible. Intel is going to launch a 28-core CPU, and AMD is introducing a 32-core CPU. Awesome, core wars. And here’s RGB RAM because stuffing a case full of cold cathode lighting is sooo early-2000s.

Need a reverse engineering challenge? Here’s something from American Science and Surplus. It’s a 48 x 12 LED matrix, loaded up with driver ICs and power regulators. $20 a piece, so stock up and save.

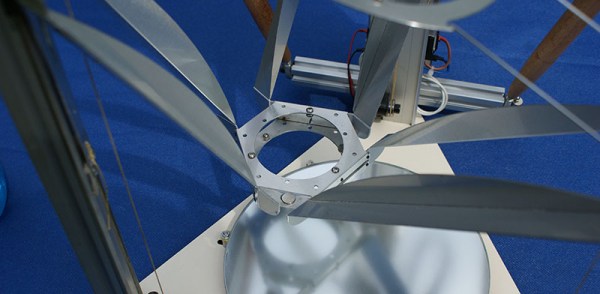

Finally, the main event. The biggest story in aviation this week is that a media embargo has lifted on the Kitty Hawk Flyer. Kitty Hawk is a startup funded by Larry Page, CEO’d by Sebastian Thrun, and has received $6.5 M in funding. The Flyer, a one-man decacopter, was announced to the world through CNN Money and Casey Neistat. It should be noted that in the entire media landscape, these are the two outlets most ignorant of aviation: CNN needs no explanation, and Neistat flies quadcopters through the Hudson River Corridor at 1000 feet AGL. Additionally, Kitty Hawk is not exhibiting at AirVenture next month, which leads me to believe Kitty Hawk is trying to stay out of the aviation industry or simply doesn’t want knowledgeable people asking them questions. But I digress.

The Kitty Hawk Flyer is being promoted by the company as “a personal flying vehicle… to make flying part of everyday life” and a machine that will give you, “a world free from traffic”. It is being billed by CNN and Neistat as ‘a flying car’. Kitty Hawk is just fine with allowing the media to call it as such. Additionally, Sebastian Thrun is making claims about the Flyer that are disingenuous at best, outright illegal at worst, and should draw the ire of any investors.

In the CNN Money piece, Thrun claims the Flyer is capable of traveling at 100 miles per hour, which would be illegal. The Flier is certified as a Part 103 Ultralight, and under that regulation the Flyer “is not capable of more than 55 knots calibrated airspeed at full power in level flight.” The Flyer may also be overweight. The first version of the Flyer was basically a decacopter with a seat, and weighed in at 220 pounds. Part 103 regulations have a limit of 254 pounds, and it’s entirely possible there are more than 34 pounds of chassis and fiberglass on the latest version. I should also mention the safety training, while not required for a Part 103 ultralight, is insufficient: Casey Neistat’s underwater egress training was done in a Chuck E. Cheese-style ball pit. You can breathe in a ball pit, you can’t breathe underwater.

But legality aside, a Part 103 ‘flying car’ is just about the dumbest idea ever. You can’t use it to commute, and you’re welcome to call your local FSDO to confirm that. You’re not going to fly it in New York City or San Francisco because there are airports in the way. At best, this is a ‘flying ATV’ that you would take out on your farm; a toy for rich people. At worst, it’s the latest example of the Silicon Valley philosophy of ‘ignore laws and break things’.