While Apple weren’t the first to invent high-DPI displays or to put them into consumer electronics, they did popularize them fairly effectively with the Retina displays in the early 2010s and made a huge number of them in the following years. The computers they’re attached to are getting up there in age, though, and although these displays are still functional it isn’t quite as straightforward to use them outside of their Apple-approved use. [David] demonstrates one way of getting this done by turning a 5k iMac into an external monitor.

The first attempt at getting a usable monitor from the old iMac was something called a Luna Display, but this didn’t have a satisfying latency. Instead, [David] turned to replacing the LCD driver board with a model called the R1811. This one had a number of problems including uneven backlighting, so he tried a second, less expensive board called the T18. This one only has 8-bit color instead of the 10-bit supported by the R1811 but [David] couldn’t personally tell the difference, and since it solved the other issues with the R1811 he went with this one. After mounting the new driver board and routing all of the wires, he also replaced the webcam with an external Logitech model and upgraded the speakers as well.

Even when counting the costs for both driver boards, the bill for this conversion comes in well under the cost of a new monitor of comparable quality from Apple, a company less concerned about innovation these days than overcharging their (admittedly willing) customers. For just a bit of effort, though, these older iMacs and other similar Apple machines with 5k displays can be repurposed to something relatively modern and still usable. Others have done similar projects and funded the upgrades by selling off the old parts.

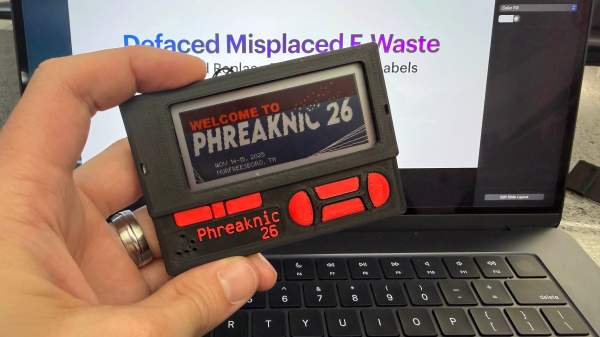

Another hacker assisting with the badge project, [Mog], noticed that the spacing of the programming pads on the PCB was very close to the spacing of a DB9/DE9 cable. This gave way to a very clever hack for programming the badges: putting pogo pins into a female connector. The other end of the cable was connected to a TI CC Debugger which was used to program the firmware on the displays. But along the way, even this part of the project got an upgrade with moving to an ESP32 for flashing firmware, allowing for firmware updates without a host computer.

Another hacker assisting with the badge project, [Mog], noticed that the spacing of the programming pads on the PCB was very close to the spacing of a DB9/DE9 cable. This gave way to a very clever hack for programming the badges: putting pogo pins into a female connector. The other end of the cable was connected to a TI CC Debugger which was used to program the firmware on the displays. But along the way, even this part of the project got an upgrade with moving to an ESP32 for flashing firmware, allowing for firmware updates without a host computer.