There was a time when buying a new radio was something many hams could never afford to do. Then came the super cheap — and super controversial — VHF and UHF radios from China. But as they say, you get what you pay for. The often oddly named handhelds like Baofeng and Wouxun are sometimes odd to work with and may have questionable RF outputs. A new radio has a less tongue-twisting English name and many improved features for about $50 — the Talkpod A36Plus and [Josh] shows us how they work in a video that you can see below.

The new features are generally good. For example, the radio can pick up AM in the aircraft band, something most of these cheap radios won’t do. It works on VHF and UHF bands but also picks up FM broadcasts. The USB-C connector is welcome, and the screen is large and colorful. It has 500 channels and IP5 water resistance.

There were a few issues, though. If you want to use it as a scanner, it’s not very fast. The radio comes with a programming cable, but apparently, it uses an odd USB chipset that may give you some driver issues. The biggest problem, though, is that it has, according to the video, excessive spurious emissions. The power isn’t that high, and the antenna probably filters off some of it, too. But creating interference across the band isn’t very polite.

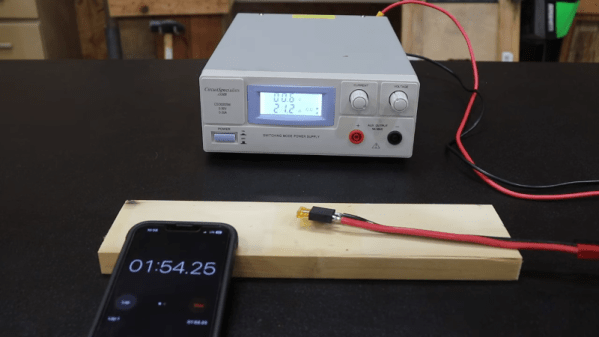

How bad are the harmonics? Well, [Josh] hooks up a spectrum analyzer and also shows how a radio tuned to the second harmonic easily picks up the transmission. Of course, no radio is perfect, but it seems like it does have very strong harmonic emissions. Of course, it may or may not be any worse than similar cheap radios. They are probably all above the legal limits, and it is just a matter of degrees.

These little radios won’t directly work the world — you need an HF radio for that, generally. They will let you connect to local repeaters, though. Some of those cheap radios can lead to interesting projects, too.

Continue reading “Cheap Ham Radio Improves The Low End UI If Not The RF” →