For apparently inexplicable reasons, the price of thermal imaging cameras has been dropping precipitously over the last few years, but there are still cool things you can do with infrared temperature sensors.

A few years ago – and while he was still writing for us – [Jeremy] came across an absurdly clever thermal imaging camera. Instead of expensive silicon, this thermal camera uses a flashlight with an RGB LED, a cheap IR temperature sensor, and a camera set up to take long exposures. By shining this flashlight/IR sensor around a dark room, a camera with a wide-open shutter can record color-coded thermal images of just about anything.

Since then, an interesting product appeared on the market. It’s the Black & Decker TLD100 Thermal Leak Detector, and it’s basically an infrared thermometer and LED flashlight stuffed into one neat package. In other words, it’s the exact same thing we saw two years ago. We’d like to thank at least one Black & Decker engineer for their readership.

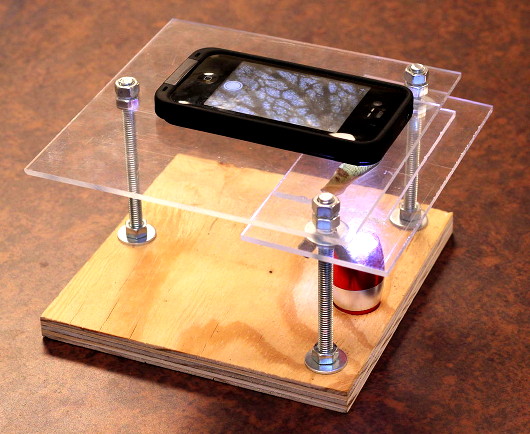

[Jeremy] took this cheap, off-the-shelf leak detector and did what anyone would do after realizing where the idea behind it came from. He set up his camera, turned off the lights, and opened the shutter of his camera. The results, like the original post, don’t offer the same thermal resolution as a real thermal camera. That doesn’t mean it’s still not a great idea, though.