Suppose that you want to get rid of a whole lot of mosquitoes with a quadcopter drone by chopping them up in the rotor blades. If you had really good eyesight and pretty amazing piloting skills, you could maybe fly the drone yourself, but honestly this looks like it should be automated. [Alex Toussaint] took us on a tour of how far he has gotten toward that goal in his amazingly broad-ranging 2024 Superconference talk. (Embedded below.)

The end result is an amazing 380-element phased sonar array that allows him to detect the location of mosquitoes in mid-air, identifying them by their particular micro-doppler return signature. It’s an amazing gadget called LeSonar2, that he has open-sourced, and that doubtless has many other applications at the tweak of an algorithm.

Rolling back in time a little bit, the talk starts off with [Alex]’s thoughts about self-guiding drones in general. For obstacle avoidance, you might think of using a camera, but they can be heavy and require a lot of expensive computation. [Alex] favored ultrasonic range finding. But then an array of ultrasonic range finders could locate smaller objects and more precisely than the single ranger that you probably have in mind. This got [Alex] into beamforming and he built an early prototype, which we’ve actually covered in the past. If you’re into this sort of thing, the talk contains a very nice description of the necessary DSP.

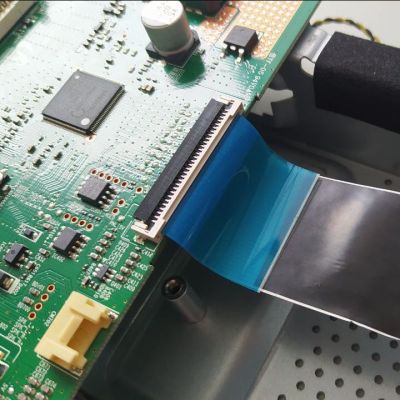

[Alex]’s big breakthrough, though, came with shrinking down the ultrasonic receivers. The angular resolution that you can resolve with a beam-forming array is limited by the distance between the microphone elements, and traditional ultrasonic devices like we use in cars are kinda bulky. So here comes a hack: the TDK T3902 MEMS microphones work just fine up into the ultrasound range, even though they’re designed for human hearing. Combining 380 of these in a very tightly packed array, and pushing all of their parallel data into an FPGA for computation, lead to the LeSonar2. Bigger transducers put out ultrasound pulses, the FPGA does some very intense filtering and combining of the output of each microphone, and the resulting 3D range data is sent out over USB.

[Alex]’s big breakthrough, though, came with shrinking down the ultrasonic receivers. The angular resolution that you can resolve with a beam-forming array is limited by the distance between the microphone elements, and traditional ultrasonic devices like we use in cars are kinda bulky. So here comes a hack: the TDK T3902 MEMS microphones work just fine up into the ultrasound range, even though they’re designed for human hearing. Combining 380 of these in a very tightly packed array, and pushing all of their parallel data into an FPGA for computation, lead to the LeSonar2. Bigger transducers put out ultrasound pulses, the FPGA does some very intense filtering and combining of the output of each microphone, and the resulting 3D range data is sent out over USB.

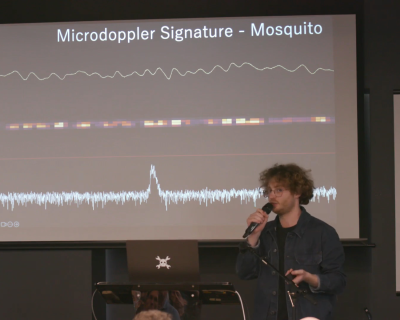

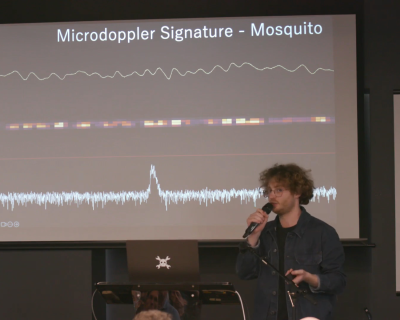

After a marvelous demo of the device, we get to the end-game application: finding and identifying mosquitoes in mid-air. If you don’t want to kill flies, wasps, bees, or other useful pollinators while eradicating the tiny little bloodsuckers that are the drone’s target, you need to be able to not only locate bugs, but discriminate mosquitoes from the others.

After a marvelous demo of the device, we get to the end-game application: finding and identifying mosquitoes in mid-air. If you don’t want to kill flies, wasps, bees, or other useful pollinators while eradicating the tiny little bloodsuckers that are the drone’s target, you need to be able to not only locate bugs, but discriminate mosquitoes from the others.

For this, he uses the micro-doppler signatures that the different wing beats of the various insects put out. Wasps have a very wide-band doppler echo – their relatively long and thin wings are moving slower at the roots than at the tips. Flies, on the other hand, have stubbier wings, and emit a tighter echo signal. The mosquito signal is even tighter.

If you told us that you could use sonar to detect mosquitoes at a distance of a few meters, much less locate them and differentiate them from their other insect brethren, we would have thought that it was impossible. But [Alex] and his team are building these devices, and you can even build one yourself if you want. So watch the talk, learn about phased arrays, and start daydreaming about what you would use something like this for.

Continue reading “Supercon 2024: Killing Mosquitoes With Freaking Drones, And Sonar” →