One of our newer writers, [Tyler August], recently wrote a love letter to plasma TV technology. Sitting between the ubiquitous LCD and the vanishing CRT, the plasma TV had its moment in the sun, but never became quite as popular as either of the other display techs, for all sorts of reasons. By all means, go read his article if you’re interested in the details. I’ll freely admit that it had me thinking that I needed a plasma TV.

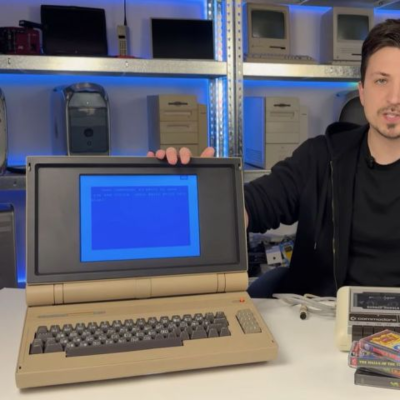

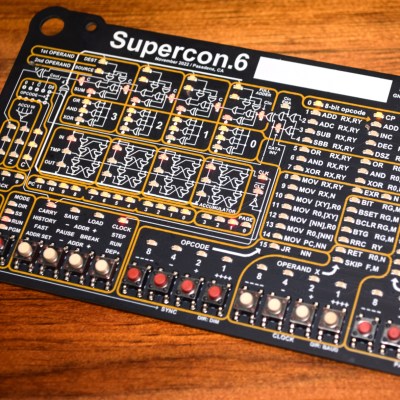

I don’t, of course. But why do I, and probably a bunch of you out there, like old and/or odd tech? Take [Tyler]’s plasma fetish, for instance, or many people’s love for VFD or nixie tube displays. At Supercon, a number of people had hit up Apex Electronics, a local surplus store, and came away with some sweet old LED character displays. And I’ll admit to having two handfuls of these displays in my to-hack-on drawer that I bought surplus a decade ago because they’re so cute.

It’s not nostalgia. [Tyler] never had a plasma growing up, and those LED displays were already obsolete before the gang of folks who had bought them were even born. And it’s not simply that it’s old junk – the objects of our desire were mostly all reasonably fancy tech back in their day. And I think that’s part of the key.

My theory is that, as time and tech progresses, we see these truly amazing new developments become commonplace, and get forgotten by virtue of their ever-presence. For a while, having a glowing character display in your car stereo would have been truly futuristic, and then when the VFD went mainstream, it kind of faded into our ambient technological background noise. But now that we all have high-res entertainment consoles in our cars, which are frankly basically just a cheap tablet computer (see what I did there?), the VFD becomes an object of wonder again because it’s rare.

Which is not to say that LCD displays are anything short of amazing. Count up the rows and columns of pixels, and multiply by three for RGB, and that’s how many nanoscale ITO traces there are on the screen of even the cheapest display these days. But we take it for granted because we are surrounded by cheap screens.

I think we like older, odder tech because we see it more easily for the wonder that it is because it’s no longer commonplace. But that doesn’t mean that our current “boring” tech is any less impressive. Maybe the moral of the story is to try to approach and appreciate what we’ve got now with new eyes. Pretend you’re coming in from the future and finding this “old” gear. Maybe try to figure out how it must have worked.