The use of disinfectants is not a new thing, but a major disadvantage with most common disinfectants is that they are only effective in the short term. After applying bleach, alcohol or other disinfectant to the surface, the disinfectant’s effect quickly fades as the liquid evaporates. Ideally the disinfectant would remain on the surface, ready to disinfect when needed.

According to researchers at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (HKUST), the solution may lie in a heat-sensitive coating that releases disinfectant when it’s needed. This Multilevel Antimicrobial Polymer (MAP-1) can remain effective for as long as 90 days, depending on how often the surface is touched or otherwise used.

MAP-1 consists out of polymer strands of a material that prevents viruses and bacteria from attaching to its surface, while disrupting its outside surface. Effectively this has the potential to inactivate (kill) most viruses and harmful bacteria that come into contact with it.

MAP-1 is currently being deployed in Hong Kong, where public places such as schools, malls and sport facilities have had the coating applied. It costs between US $2,600 and US $50,000 to treat an area, which is not cheap, but would be cheaper than shutting down such a facility for regular surface disinfecting.

Although it still has to be determined that MAP-1 is as effective as hoped, it is another example of an antimicrobial surface, a material that is designed to be as incompatible with sustaining viruses and bacteria as possible. In the past copper and its alloys have been commonly used for this purpose, but a polymer coating is obviously more versatile. From the point of view of today’s pandemic, making surfaces incapable of hosting viruses definitely can be regarded as highly necessary.

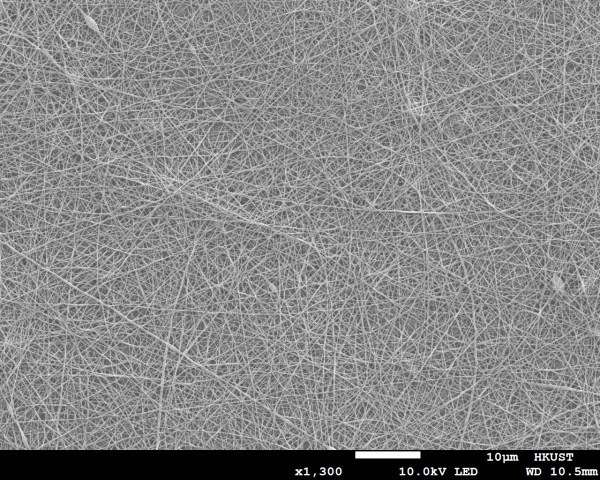

(Pictured: a MAP-1 coating on a surface, courtesy of HKUST)