Even in the face of an Internet of Things grasping for a useful use case, an Internet-connected clock is actually a great idea. With a cheap WiFi module and a connection to an NTP server, any clock can become an atomic clock. [Jim] decided to experiment with the ESP8266 to turn a cheap analog clock into something that will display network time using a bunch of gears and motors.

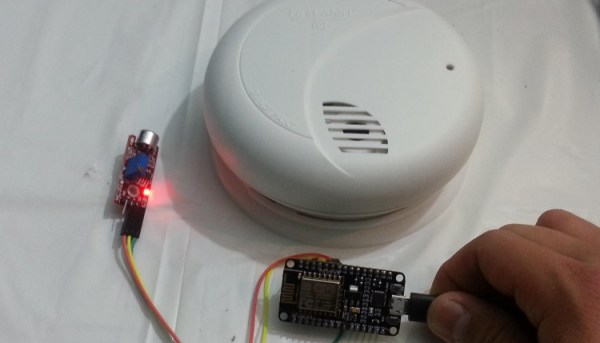

The clock [Jim] chose for this build is an extremely cheap clock pulled right from the shelves of WalMart. This clock uses a standard quartz clock mechanism, powered by a single AA cell. The coils in these quartz movements can be easily controlled by pulsing current through them, and with a few a few transistors and diodes set up in an h-bridge, an ESP8266 is quite good at setting the time on this clock.

The software for this clock first connects to the WiFi network, then checks an NTP server for the true time. Once the ESP8266 gets the time, it starts hammering the coil in the clock movement until the hands are where they should be.

[Jim] says the project needs a bit of work – there is no feedback on the clock to determine the position of the hands. Instead, the time is just set assuming the clock hands started off at 12:00. Still, even with that small fault, it’s a great build and a great exploit of what can be done with a cheap quarts clock movement.

If you’d like to go to the opposite extreme of cost and complexity, how about a DIY retro atomic clock? Or if you’re in need of a wakeup, we’ve seen a ton of alarm clock posts in the past few weeks.