Students of the Samara State Aerospace University are having trouble getting a signal from their satellite, SamSat-218D. They are now reaching out to the radio amateur community, inviting everybody with sufficiently sensitive UHF VHF band (144 MHz) equipment to help by listening to SamSat-218D. The satellite was entirely built by students and went into space on board of a Soyuz-2 rocket on April 26, 2016. This is their call (translated by Google):

amateur radio222 Articles

Listen To Meteors Live

When the big annual meteor showers come around, you can often find us driving up to a mountaintop to escape light pollution and watching the skies for a while. But what to do when it’s cloudy? Or when you’re just too lazy to leave your computer monitor? One solution is to listen to meteors online! (Yeah, it’s not the same.)

Meteors leave a trail of ionized gas in their wake. That’s what you see when you’re watching the “shooting stars”. Besides glowing, this gas also reflects radio waves, so you could in principle listen for reflections of terrestrial broadcasts that bounce off of the meteors’ tails. This is the basis of the meteor burst communication mode.

[Ciprian Sufitchi, N2YO] set up his system using nothing more than a cheap RTL-SDR dongle and a Yagi antenna, which he describes in his writeup (PDF) on meteor echoes. The trick is to find a strong signal broadcast from the earth that’s in the 40-70 MHz region where the atmosphere is most transparent so that you get a good signal.

This used to be easy, because analog TV stations would put out hundreds of kilowatts in these bands. Now, with the transition to digital TV, things are a lot quieter. But there are still a few hold-outs. If you’re in the eastern half of the USA, for instance, there’s a transmitter in Ontario, Canada that’s still broadcasting analog on channel 2. Simply point your antenna at Ontario, aim it up into the ionosphere, and you’re all set.

We’re interested in anyone in Europe knows of similar powerful emitters in these bands.

As you’d expect, we’ve covered meteor burst before, but the ease of installation provided by the SDR + Yagi solution is ridiculous. And speaking of ridiculous, how about communicating by bouncing signals off of passing airplanes? What will those ham radio folks think of next?

How Low Can You Go? The World Of QRP Operation

Newly minted hams like me generally find themselves asking, “What now?” after getting their tickets. Amateur radio has a lot of different sub-disciplines, ranging from volunteering for public service gigs to contesting, the closest thing the hobby has to a full-contact sport. But as I explore my options in the world of ham radio, I keep coming back to the one discipline that seems like the purest technical expression of the art and science of radio communication – low-power operation, or what’s known to hams as QRP. With QRP you can literally talk with someone across the planet on less power than it takes to run a night-light using a radio you built in an Altoids tin. Now that’s a challenge I can sink my teeth into.

Continue reading “How Low Can You Go? The World Of QRP Operation”

Sage Advice For The New Ham

If you’re on the edge about getting your amateur radio license, just go do it and worry about the details later. But once you’ve done that, you’re going to need to know a little bit about the established culture and practices of the modern ham — the details.

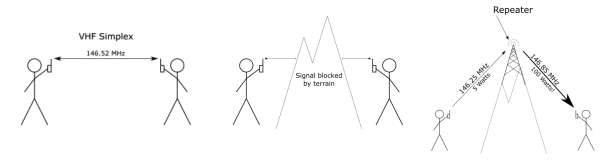

Toward that end, [McSteve] has written up a (so far) two-part introductory series about ham radio. His first article is fairly general, and lays out many of the traditional applications of ham radio: chatting with other humans using the old-fashioned analog modes. You know, radio stuff.

The second article focuses more on using repeaters. Repeaters can be a confusing topic for new radio operators: there are two frequencies — one for transmitting and one for receiving — and funny control tones (CTCSS) etc. This article is particularly useful for the new ham, because you’re likely to have a relatively low powered radio that would gain the most from using a repeater, and because the technology and traditions of repeater usage are a bit arcane.

So if you’re thinking about getting your license, do it already. And then read through these two pages and you’re good to go. We can’t wait to see what [McSteve] writes up next.

The New Heathkit Strikes Again

Alright, this is getting embarrassing.

The rebooted Heathkit has added another kit to its offerings. This time it’s an inexplicably simple and exorbitantly priced antenna for the 2-meter band. It joins their equally bizarre and pricey AM radio kit in the new product lineup, and frankly we’re just baffled by the whole affair.

About the most charitable thing you can say about their “Pipetenna” is that it’ll probably work really well. Heathkit throws some impedance and SWR charts on the website, and the numbers look pretty good. Although Heathkit doesn’t divulge the design within the “waterproof – yes, waterproof!” housing, at 6 dBi gain and only five feet long, we’re going to guess this is basically a Slim Jim antenna stuffed in a housing made of Schedule 40 PVC tubing. About the only “high-end” component we can see is the N-type coax connector, but that just means most hams will need and adapter for their more standard PL-259 terminated coax.

Regardless of design, it’s hard to imagine how Heathkit could stuff enough technology into this antenna to justify the $149 price. Hams have been building antennas like these forever from bits and pieces of wire lying around. Even if you bought all new components, including the PVC pipe and fittings, you’d be hard pressed to put $50 into a homebrew version that’ll likely perform just as well.

The icing on this questionable cake, though, is the sales copy on the web page. The “wall of text” formatting, the overuse of superlatives, and the cutesy asides and quips remind us of the old DAK Industries ads that hawked cheap import electronics as the latest and greatest must-have device. There’s just something unseemly going on here, and it doesn’t befit a brand with the reputation of Heathkit.

When we reviewed Heathkit’s AM radio kit launch back in December, we questioned where the company would go next. It looks like we might have an answer now, and it appears to be “nowhere good.”

A Geek’s Revenge For Loud Neighbors

It seems [Kevin] has particularly bad luck with neighbors. His first apartment had upstairs neighbors who were apparently a dance troupe specializing in tap. His second apartment was a town house, which had a TV mounted on the opposite wall blaring American Idol with someone singing along very loudly. The people next to [Kevin]’s third apartment liked music, usually with a lot of bass, and frequently at seven in the morning. This happened every day until [Kevin] found a solution (Patreon, but only people who have adblock disabled may complain).

In a hangover-induced rage that began with thumping bass at 7AM on a Sunday, [Kevin] tore through his box of electronic scrap for every capacitor and inductor in his collection. An EMP was the only way to find any amount of peace in his life, and the electronics in his own apartment would be sacrificed for the greater good. In his fury, [Kevin] saw a Yaesu handheld radio sitting on his desk. Maybe, just maybe, if he pressed the transmit button on the right frequency, the speakers would click. The results turned out even better than expected.

With a car mount antenna pointed directly at the neighbor’s stereo, [Kevin] could transmit on a specific, obscure frequency and silence the speakers. How? At seven in the morning on a Sunday, you don’t ask questions. That’s a matter for when you tell everyone on the Internet.

Needless to say, using a radio to kill your neighbor’s electronics is illegal, and it might be a good idea for [Kevin] to take any references to this escapade off of the Internet. It would be an even better idea to not put his call sign online in the future.

That said, this is a wonderful tale of revenge. It’s not an uncommon occurrence, either. Wikihow, Yahoo Answers and Quora – the web pages ‘normies’ use for the questions troubling their soul – are sometimes unbelievably literate when it comes to unintentional electromagnetic interference, and some of the answers correctly point out grounding a stereo and putting a few ferrite beads on the speaker cables is the way to go. Getting this answer relies entirely on asking the right question, something I suspect 90% of the population is completely incapable of doing.

While [Kevin]’s tale is a grin-inducing two-minute read, You shouldn’t, under any circumstances, do anything like this. Polluting the airwaves is much worse than polluting your neighbor’s eardrums; one of them violates municipal noise codes and another is breaking federal law. It’s a good story, but don’t do it yourself.

Editor’s Note: Soon after publishing our article [Kevin] took down his post and sent us an email. He realized that what he had done wasn’t a good idea. People make mistakes and sometimes do things without thinking. But talking about why this was a bad idea is one way to help educate more people about responsible behavior. Knowing you shouldn’t do something even though you know how is one paving stone on the path to wisdom.

–Mike Szczys

The Michigan Mighty-Mite Rides Again

One of the best things about having your amateur radio license is that it allows you to legally build and operate transmitters. If you want to build a full-featured single-sideband rig with digital modes, have at it. But there’s a lot of fun to be had and a lot to learn from minimalist builds like this Michigan Mighty-Mite one-transistor 80-meter band transmitter.

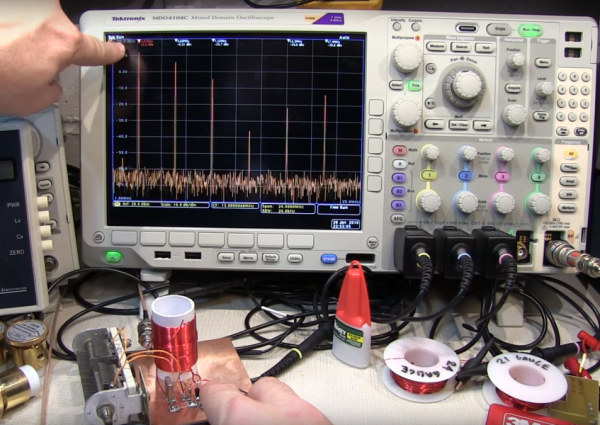

If the MMM moniker sounds familiar, it may be because of this recent post. And in fact, [W2AEW]’s build was inspired by the same SolderSmoke blog posts that started [Paul Hodges] on the road to his breadboard and beer can build. [W2AEW]’s build is a bit sleeker, to be sure, but where the video really shines is in the exploration and improvement of the signal quality. The basic Mighty-Mite outputs a pretty dirty signal – [W2AEW]’s scope revealed 5 major harmonic spikes, and what was supposed to be a nice sine wave was full of divots and potholes. There’s only so much one transistor, a colorburst crystal and a couple of capacitors can do, so the video treats us to an explanation of the design of the low-pass filter needed to get rid of the harmonics and clean up the output into a nice solid sine wave.

If your Morse skills aren’t where they should be to take advantage of the Might-Mite’s CW-only mode, then you’ll need to look at other modulations. Maybe a tiny FM transmitter would suit your needs better?