Go to a pier, boardwalk, the tip of Manhattan, or a battlefield, and you’ll see beautifully crafted coin operated binoculars. Drop a coin in, and you’ll see the Statue of Liberty, a container ship rolling coal, or a beautiful pasture that was once the site of terrific horrors. For just a quarter, these binoculars allow you to take in the sights, but simply by virtue of the location of where these machines are placed, you’re standing in the midsts of history. There’s so much more there. If only there was a way to experience that.

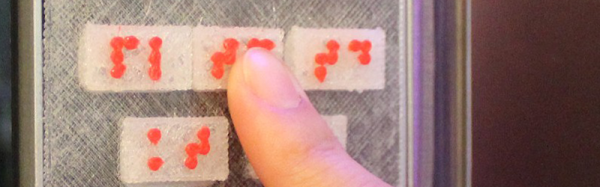

This is why [Ben Sax] is building the Perceptoscope. It’s a pair of augmented reality binoculars. Drop in a quarter, and you’ll be able to view the entirety of history for an area. Drop this in Battery Park, and you’ll be able to see the growth of Manhattan from New Amsterdam to the present day. Drop this in Gettysburg, and you’ll see a tiny town surrounded by farms become a horrorscape and turn back into a tiny town surrounded by a National Park.

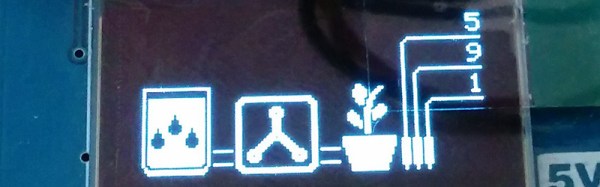

This is a long term project, with any installations hopefully lasting for decades. That means these Perceptoscopes need to be tough, both in hardware and software. For the software, [Ben] is using WebVR, virtual reality rendering inside a browser. This means the electronics can just be a tablet that can be swapped in and out.

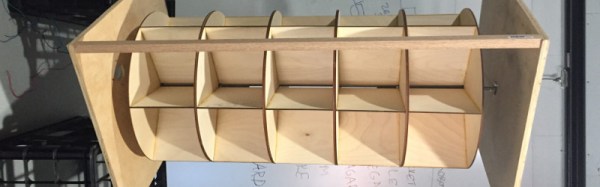

The hardware, though, isn’t as simple. This is going to be a device running in the rain, snow, and freezing weather for decades. Everything must be overbuilt, and already [Ben] has spent far too much time working on the bearing blocks.

Although this is an entry for The Hackaday Prize, it was ‘pulled out’, so to speak, to be a part of the Supplyframe DesignLab inaugural class. The DesignLab is a shop filled with the best tools you can imagine, and exists for only one goal: we’re getting the best designers in there to build cool stuff. The Perceptoscope has been the subject of a few videos coming out of the DesignLab, you can check those out below.

Continue reading “Hackaday Prize Entry: Augmented Reality Historical Reenactments”