Source control is often the first step when starting a new project (or it should be, we’d hope!). Breaking changes down into smaller chunks and managing the changes between them makes it easier to share work between developers and to catch and revert mistakes after they happen. As project complexity increases it’s often desirable to add other nice to have features on top of it like automatic build, test, and deployment.

These are less common for firmware but automatic builds (“Continuous Integration” or CI) is repetitively easy to setup and instantly gives you an eye on a range of potential problems. Forget to check in that new header? Source won’t build. Tweaked the linker script and broke something? Software won’t build. Renamed a variable but forgot a few references? Software won’t build. But just building the software is only the beginning. [noseglasses] put together a tool called elf_diff to make tracking binary changes easier, and it’s a nifty addition to any build pipeline.

In firmware-land, where flash space can be limited, it’s nice to keep a handle on code size. This can be done a number of ways. Manual inspection of .map files (colloquially “mapfiles”) is the easiest place to start but not conducive to automatic tracking over time. Mapfiles are generated by the linker and track the compiled sizes of object files generated during build, as well as the flash and RAM layouts of the final output files. Here’s an example generated by GCC from a small electronic badge. This is a relatively simple single purpose device, and the file is already about 4000 lines long. Want to figure out how much codespace a function takes up? That’s in there but you’re going to need to dig for it.

In firmware-land, where flash space can be limited, it’s nice to keep a handle on code size. This can be done a number of ways. Manual inspection of .map files (colloquially “mapfiles”) is the easiest place to start but not conducive to automatic tracking over time. Mapfiles are generated by the linker and track the compiled sizes of object files generated during build, as well as the flash and RAM layouts of the final output files. Here’s an example generated by GCC from a small electronic badge. This is a relatively simple single purpose device, and the file is already about 4000 lines long. Want to figure out how much codespace a function takes up? That’s in there but you’re going to need to dig for it.

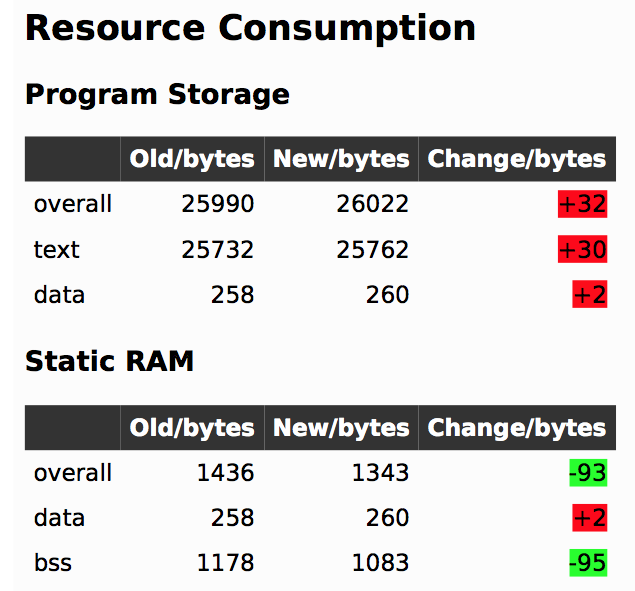

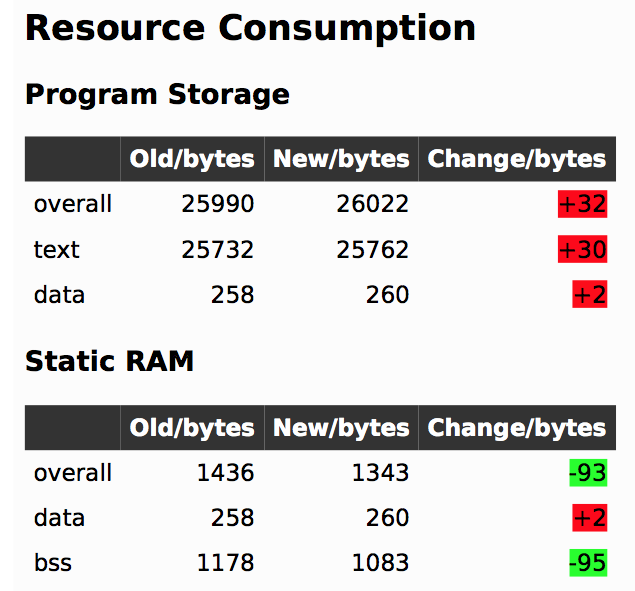

elf_diff automates that process by wrapping it up in a handy report which can be generated automatically as part of a CI pipeline. Fundamentally the tool takes as inputs an old and a new ELF file and generates HTML or PDF reports like this one that include readouts like the image shown here. The resulting table highlights a few classes of binary changes. The most prominent is size change for the code and RAM sections, but it also breaks down code size changes in individual symbols (think structures and functions). [noseglasses] has a companion script to make the CI process easier by compiling a pair of firmware files and running elf_diff over them to generate reports. This might be a useful starting point for your own build system integration.

Thanks [obra] for the tip! Have any tips and tricks for applying modern software practices to firmware development? Tell us in the comments!

In firmware-land, where flash space can be limited, it’s nice to keep a handle on code size. This can be done a number of ways. Manual inspection of .map files (colloquially “mapfiles”) is the easiest place to start but not conducive to automatic tracking over time. Mapfiles are generated by the linker and track the compiled sizes of object files generated during build, as well as the flash and RAM layouts of the final output files.

In firmware-land, where flash space can be limited, it’s nice to keep a handle on code size. This can be done a number of ways. Manual inspection of .map files (colloquially “mapfiles”) is the easiest place to start but not conducive to automatic tracking over time. Mapfiles are generated by the linker and track the compiled sizes of object files generated during build, as well as the flash and RAM layouts of the final output files.