[TeachingTech] has a video covering the OpenScan Mini that does a great job of showing the workflow, hardware, and processing method for turning small objects into high-quality 3D models. If you’re at all interested but unsure where or how to start, the video makes an excellent guide.

We’ve covered the OpenScan project in the past, and the project has progressed quite a bit since then. [TeachingTech] demonstrates scanning a number of small and intricate objects, including a key, to create 3D models with excellent dimensional accuracy.

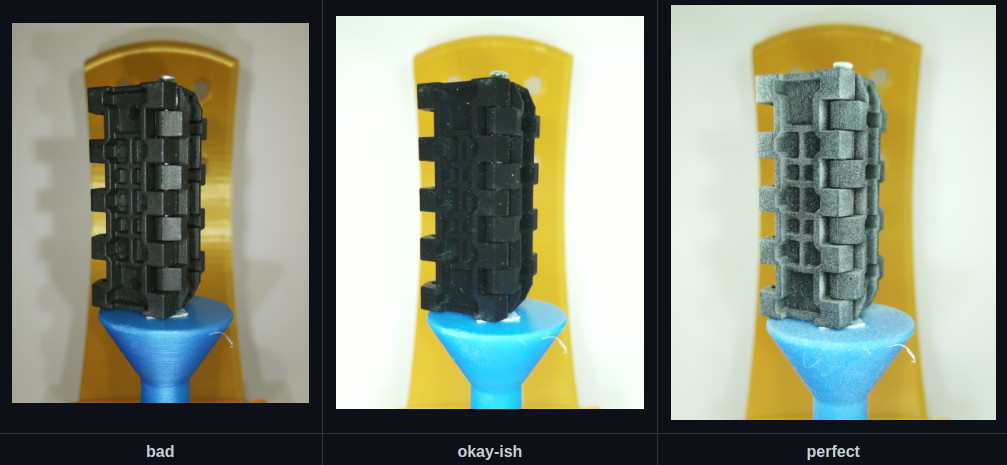

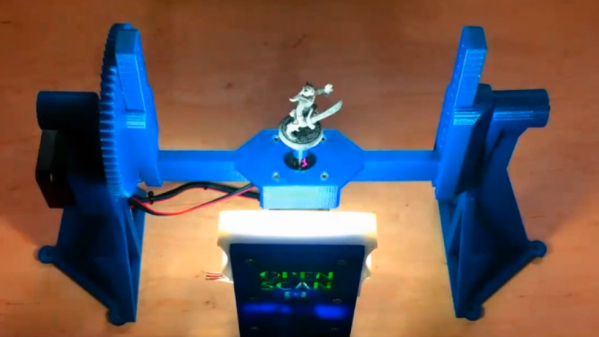

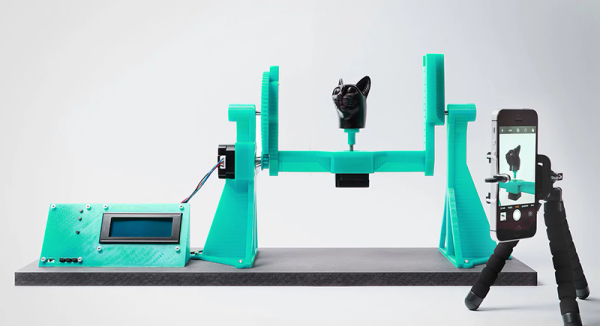

[Thomas Megel]’s OpenScan project is a DIY project that, at its heart, is an automated camera rig that takes a series of highly-controlled photographs. Those photographs are then used in a process called photogrammetry to generate a 3D model from the source images. Since the quality of the source images is absolutely critical to getting good results, the OpenScan hardware platform plays a pivotal role.

[Thomas Megel]’s OpenScan project is a DIY project that, at its heart, is an automated camera rig that takes a series of highly-controlled photographs. Those photographs are then used in a process called photogrammetry to generate a 3D model from the source images. Since the quality of the source images is absolutely critical to getting good results, the OpenScan hardware platform plays a pivotal role.

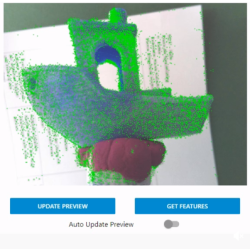

Once one has good quality images, the photogrammetry process itself can be done in any number of ways. One can feed images from OpenScan into a program like Meshroom, or one may choose to use the optional cloud service that OpenScan offers (originally created as an internal tool, it is made available as a convenient processing option.)

It’s really nice to have a video showing how the whole workflow works, and highlighting the quality of the results as well as contrasting them with other 3D scanning methods. We’ve previously talked about 3D scanning and what it does (and doesn’t) do well, and the results from the OpenScan Mini are fantastic. It might be limited to small objects, but it does a wonderful job on them. See it all for yourself in the video below.

Continue reading “Watch The OpenScan DIY 3D Scanner In Action”