Radio experimenters often need a variable capacitor to tune their circuits, as the saying goes, for maximum smoke. In decades past these were readily available from almost any scrap radio, but the varicap diode and then the PLL have removed the need for them in consumer electronics. There have been various attempts at building variable capacitors, and here’s [radiofun232] with a novel approach.

A traditional tuning capacitor has a set of meshed semicircular plates that have more of their surface facing each other depending on how far their shaft is turned. The capacitor presented in the first video below has two plates joined by a hinge in a similar manner to the covers of a book. It’s made of tinplate, and the plates can be opened or closed by means of a screw.

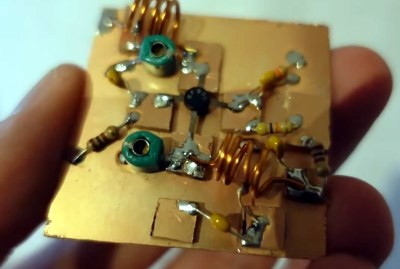

The result is a capacitor with a range from 50 to 150 picofarads, and in the second video we can see it used with a simple transistor oscillator to make a variable frequency oscillator. This can form the basis of a simple direct conversion receiver.

We like this device, it’s simple and a bit rough and ready, but it’s a very effective. If you’d like to see another unusual take on a variable capacitor, take a look at this one using drinks cans.

Continue reading “It’s A Variable Capacitor, But Not As We Know It”