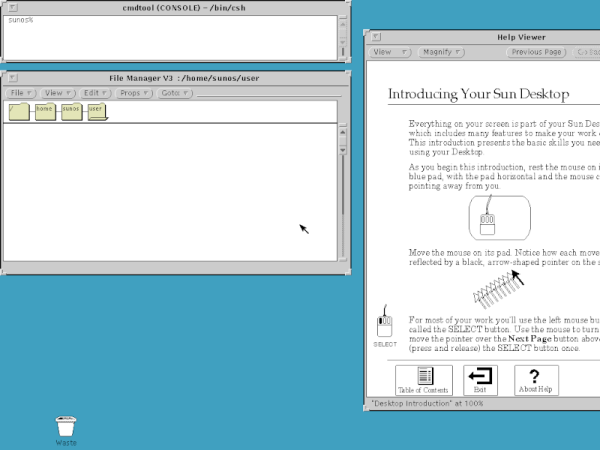

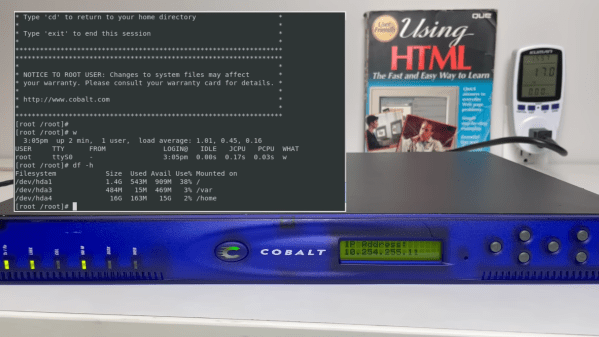

When the IBM PC first came out, it was little more than a toy. The serious people had Sun or Apollo workstations. These ran Unix, and had nice (for the day) displays and network connections. They were also expensive, especially considering what you got. But now, QEMU can let you relive the glory days of the old Sun workstations by booting SunOS 4 (AKA Solaris 1.1.2) on your PC today. [John Millikin] shows you how in step-by-step detail.

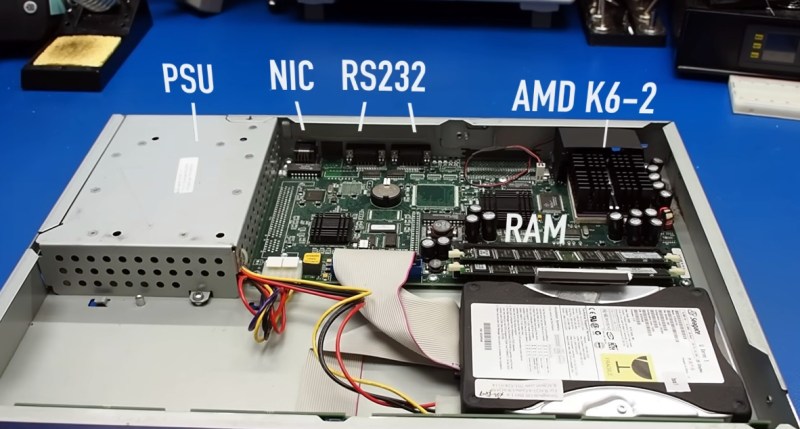

There’s little doubt your PC has enough power to pull it off. The SUN-3 introduced in 1985 might have 8MB or 16MB of RAM and a 16.67 MHz CPU. In 1985, an 3/75 (which, admittedly, had a Motorola CPU and not a SPARC CPU) with 4MB of RAM and a monochrome monitor cost almost $16,000, and that didn’t include software or the network adapter. You’d need that network adapter to boot off the network, too, unless you sprung another $6,000 for a 71 MB disk. The SPARCstation 1 showed up around 1989 and ran from $9,000 to $20,000, depending on what you needed.

Continue reading “Relive The Glory Days Of Sun Workstations”