Electrodermal activity, or galvanic skin response has a lot of practical applications. Everything from research into emotional states to significantly more off-the-wall applications like the E-meter use electrodermal activity. For his Hackaday Prize entry, [qquuiinn] is building a wearable biofeedback wristband that measures galvanic skin response that is perfect for treating anxiety or stress disorders by serving as a simple and convenient wearable device.

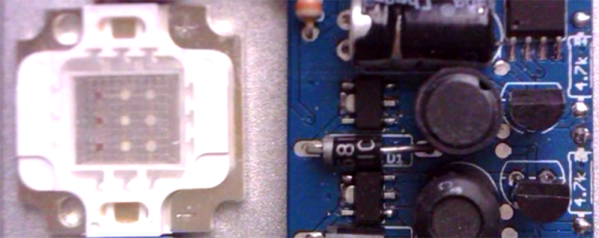

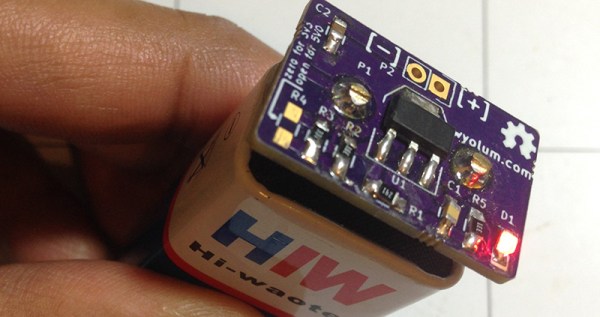

Detecting electrodermal activity has been within the capability of anyone with an ohmmeter for over a hundred years. [quin²] is doing something a little more complex than the most primitive modern means of measuring galvanic skin response and using a dual op-amp to sense the tiny changes in skin resistance. This data is fed into an ATMega328 which sends it out to a tiny LED display in the shape of an ‘x’.

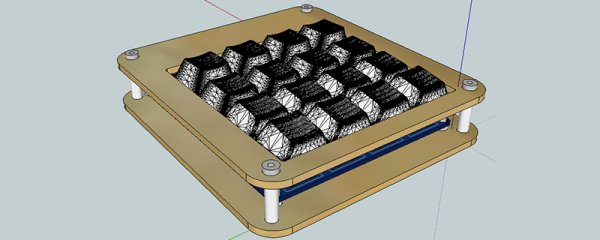

Reading electrodermal activity is easy, but doing it reliably in a wearable device is not. There are issues with the skin contacts to work though, issues with the amplifier, and putting the whole thing in a convenient package. [qquuiinn] asked the community about these problems in group discussion on the hacker channel and got a lot of really good advice. That’s a great example of what a project on hackaday.io can do, and a great project for the Hackaday Prize.