Mars is getting to be a busy place, what with helicopters buzzing around and rovers roving all about the place. Now it’s set to get a bit more crowded, with the planned descent of the newly-named Chinese Zhurong rover. Named after the god of fire from ancient Chinese mythology, the rover, which looks a little like Opportunity and Spirit and rides to the surface aboard something looking a little like the Viking lander, will carry a suite of scientific instruments around Utopia Planitia after it lands sometime this month. Details are vague; China usually plays its cards close to the vest, and generally makes announcements only when a mission is a fait accompli. But it appears the lander will leave its parking orbit, which it entered back in February, sometime this month. It’s not an easy ride, and we wish Zhurong well.

Speaking of space, satellites don’t exactly grow on trees — until they do. A few groups, including a collaboration between UPM Plywood and Finnish startup Arctic Astronautics, have announced intentions to launch nanosatellites made primarily of wood. Japanese logging company Sumitomo Forestry and Kyoto University also announced their partnership, formed with the intention to prove that wooden satellites can work. While it doesn’t exactly spring to mind as a space-age material, wood does offer certain advantages, including relative transparency to a wide range of the RF spectrum. This could potentially lead to sleeker satellite designs, since antennae and sensors could be located inside the hull. Wood also poses less of a hazard than a metal spaceframe does when the spacecraft re-enters the atmosphere. But there’s one serious disadvantage that we can see: given the soaring prices for lumber, at least here in the United States, it may soon be cheaper to build satellites out of solid titanium than wood.

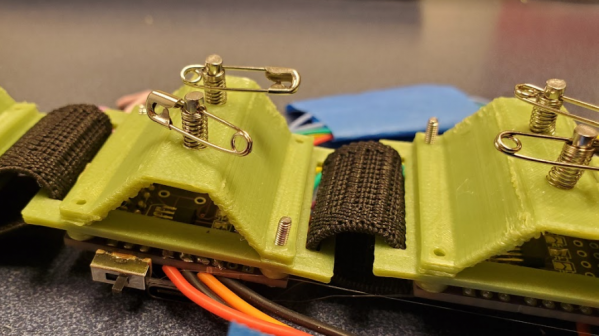

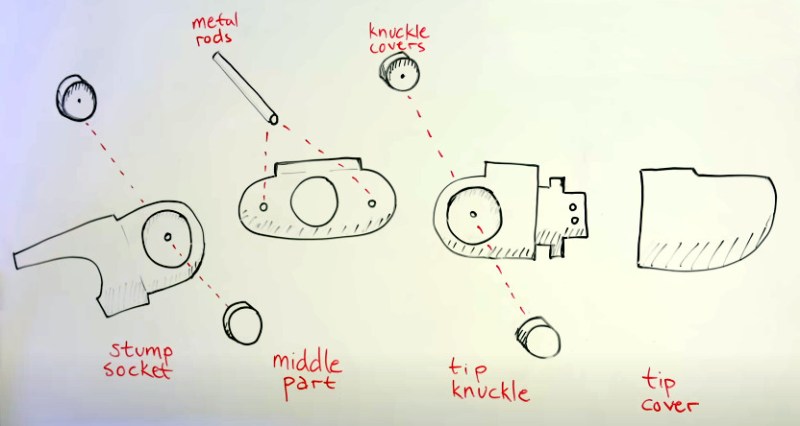

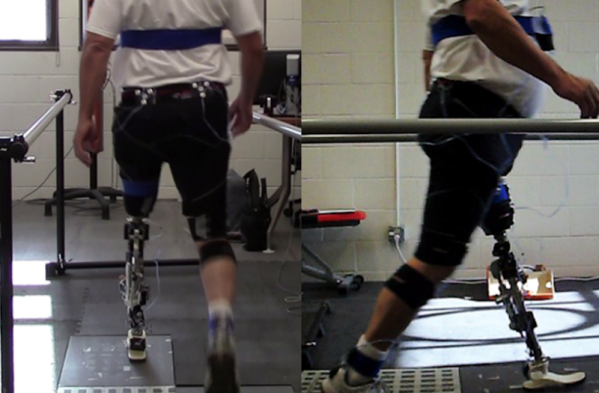

If the name Ian Davis doesn’t ring a bell with you, one look at his amazing mechanical prosthetic hand will remind you that we’ve been following his work for a while now. Ian suffered a traumatic amputation of the fingers of his left hand, leaving only his thumb and palm intact, and when his insurance wouldn’t pay for a prosthetic hand, he made his own. Ian has gone through several generations, each of which is completely mechanical and controlled only by wrist movements. The hands are truly works of mechanical genius, and Ian is now sharing what he’s learned to help out fellow hand-builders. Even if you’re not building a hand, the video is well worth watching; the intricacy of the whiffle-tree mechanism used to move the fingers is just a joy to behold, and the complexity of movement that Ian’s hand is capable of is just breathtaking.

If mechanical hands don’t spark your interest, then perhaps the engineering behind top fuel dragsters will get you going. We’ll admit that most motorsports bore us to tears, even with the benefit of in-car cameras. But there’s just something about drag cars that’s so exciting. The linked video is a great dive into the details of the sport, where engines that have to be rebuilt after just a few seconds use, fuel flows are so high that fuel lines the size of a firehouse are used, and the thrust from the engine’s exhaust actually contributes to the car’s speed. There’s plenty of slo-mo footage in the video, including great shots of what happens to the rear tires when the engine revs up. Click through the break for more!

Continue reading “Hackaday Links: May 2, 2021” →