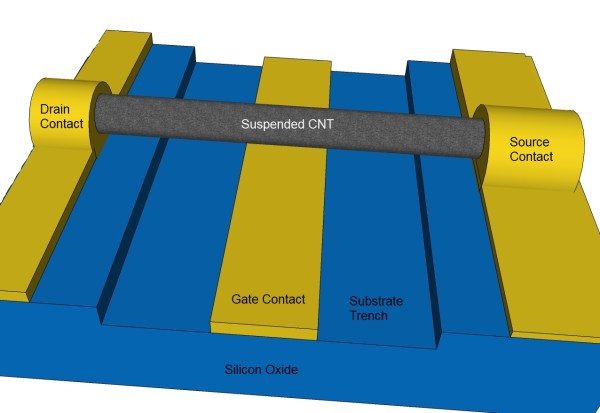

Research projects have a funny way of getting blown out of proportion by the non-experts, over-promising the often relatively small success that the dedicated folks doing the science have managed to eke out. Scaling-up cost-effectively is one of the biggest killers for commercializing research, which is why recent developments in creating carbon nanotube transistors have us hopeful.

Currently, most cutting-edge processes use FETs (Field Effect Transistors). As they’ve gotten smaller, we’ve added fins and other tricks to get around the fact that things get weird when they’re small. The industry is looking to move to GAAFETs (Gate All Around FET) as Intel and Samsung have declared their 3 nm processes (or equivalent) will use the new type of gate. As transistors have shrunk, the “off-state” leakage current has grown. GAAFETs are multi-gate devices, allowing better control of that leakage, among other things.

As usual, we’re already looking at what is past 3 nm towards 2 nm, and the concern is that GAAFET won’t scale past 3 nm. Carbon Nanotubes are an up-and-coming technology as they offer a few critical advantages. They conduct heat exceptionally well, exhibit higher transconductance, and conduct large amounts of power. In addition, they show higher electron mobility than conventional MOSFETs and often outperform them with less power even while being at larger sizes. This is all to say that they’re an awesome piece of tech with a few caveats. Continue reading “Falling Down The Carbon Rabbit Hole”

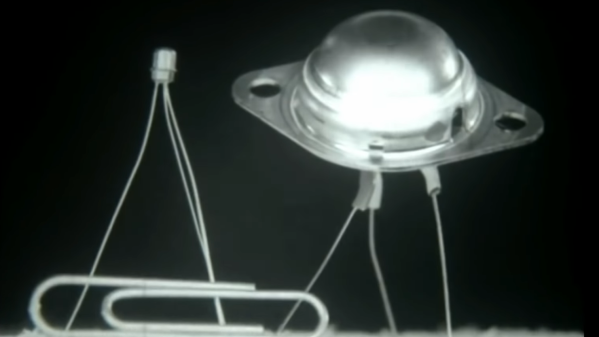

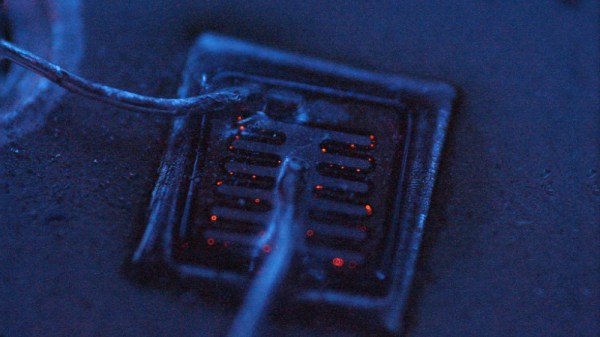

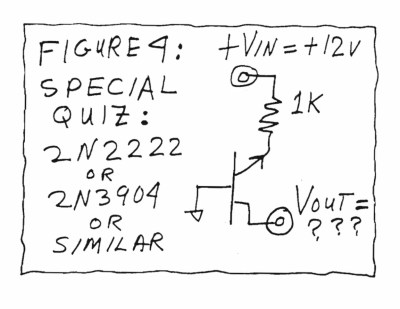

The key to the trick is the breakdown voltage of the transistor; normally somewhere around 7-8 volts for a typical small NPN transistor. At this point, where the base-emitter junction enters the breakdown regime, it begins to emit light. This light actually travels through the silicon lattice, where it reaches the base-collector junction, which acts like a photodiode under the right conditions. This generates the negative voltage seen at the collector under these conditions.

The key to the trick is the breakdown voltage of the transistor; normally somewhere around 7-8 volts for a typical small NPN transistor. At this point, where the base-emitter junction enters the breakdown regime, it begins to emit light. This light actually travels through the silicon lattice, where it reaches the base-collector junction, which acts like a photodiode under the right conditions. This generates the negative voltage seen at the collector under these conditions.