[Ryan] a.k.a. [1o57] comes from an age before anyone could ask a question, pull out their smartphone, and instantly receive an answer from the great Google mind. He thinks there’s something we have lost with our new portable cybernetic brains – the opportunity to ask a question, think about it, review what we already know, and reason out a solution. There’s a lot to be said about solving a problem all by yourself, and there’s nothing to compare to the ‘ah-ha’ moment that comes with it.

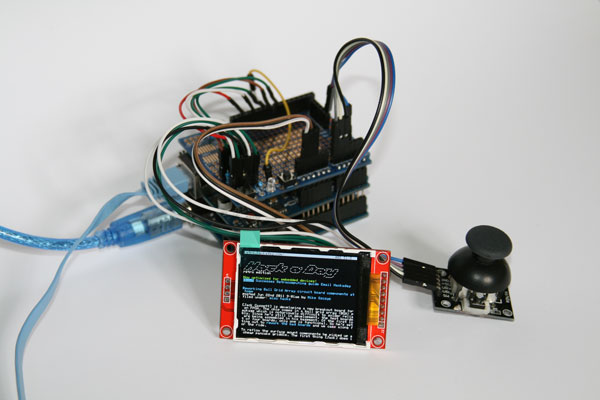

[1o57] started his Mystery Challenges at DEFCON purely by accident; he had won the TCP/IP embedded device competition one year, and the next year was looking to claim his title again. The head of the TCP/IP embedded competition had resigned from his role, and through a few emails, [1o57] took on the role himself. There was a miscommunication, though, and [1o57] was scheduled to run the TCP/IP drinking competition. This eventually morphed into a not-totally-official ‘Mystery Challenge’ that caught fire in email threads and IRC channels. Everyone wanted to beat the mystery challenge, and it was up to [1o57] to pull something out of his bag of tricks.

The first Mystery Challenge was a mechanical device with three locks ready to be picked (one was already unlocked), magnets to grab ferrous picks, and only slightly bomb-like in appearance. The next few years featured similar devices with more locks, better puzzles, and were heavy enough to make a few security officials believe [1o57] was going to blow up the Hoover dam.

With a few years of practice, [1o57] is turning crypto puzzles into an art. His DEFCON 22 badge had different lanyards that needed to be arranged to spell out a code. To solve the puzzle, you’ll need to talk to other people, a great way to meet one of [1o57]’s goals of getting all the natural introverts working together.

Oh. This talk has its own crypto challenge, something [1o57] just can’t get out of his blood:

We talked for a little bit, and 0x06 0x0a1 MFY YWXDWE MEOYOIB ASAE WBXLU BC S BLOQ ZTAO KUBDR HG SK YTTZSLBIMHB