Turn the clock back a couple of decades, and the only time the average person would have given much thought to batteries was when the power would go out, and they suddenly needed to juice up their flashlight or portable radio. But today, high-capacity batteries have become part and parcel to our increasingly digital lifestyle. In fact, there’s an excellent chance the device your reading this on is currently running on battery power, or at least, is capable of it.

So let’s get to know batteries better. What’s the chemical process that allows them to work? For that matter, what even is a battery in the first place?

It’s these questions, and more, that made up this week’s Battery Engineering Hack Chat with Dave Sopchak. Our last Hack Chat of 2022 ended up being one of the longest in recent memory, with the conversation starting over an hour before the scheduled kickoff and running another half hour beyond when emcee Dan Maloney officially made his closing remarks. Not bad for a topic that so often gets taken for granted.

Somewhat counterintuitively, the Battery Engineering Hack Chat actually started with a lively discussion about fuel cells — a subject Dave also has considerable experience with. Considering they powered the Apollo missions to the Moon back in the 1960s, you’d think by now they’d be built into the old Wagon Queen Family Truckster.

The reality is that we lack the hydrogen distribution network that would make such vehicles practical, but of course nobody is going to build that network unless there’s demand, so it’s something of a recursive problem. As for fuel cells powering our homes, Dave points out those units tend to run natural gas, making them unattractive considering the strong push towards renewable resources.

From there, the topic moves on to supercapacitors, which in turn leads to a discussion about what is and is not a battery. The average Hackaday reader surely knows that a capacitor and battery are conceptually similar in that they store energy, but the comparison ends there. As Dave explains, to be considered a true battery, there needs to be a chemical reaction. While we might not realize it, there’s actually quite a bit going on inside that nondescript lithium-ion pouch; the positive and negative electrodes will change their volume considerably when going from a discharged to charged state, a product of oxidation and reduction.

Dave goes on to say that the inherently dynamic nature of batteries is why he takes issue with so-called “solid-state batteries” that many hope will provide the next generation of portable power. A true solid-state component, that is a semiconductor device with no moving parts, would not experience changes in volume during use. So as the electrodes inside a battery experience oxidation or reduction, they cannot by definition be solid-state.

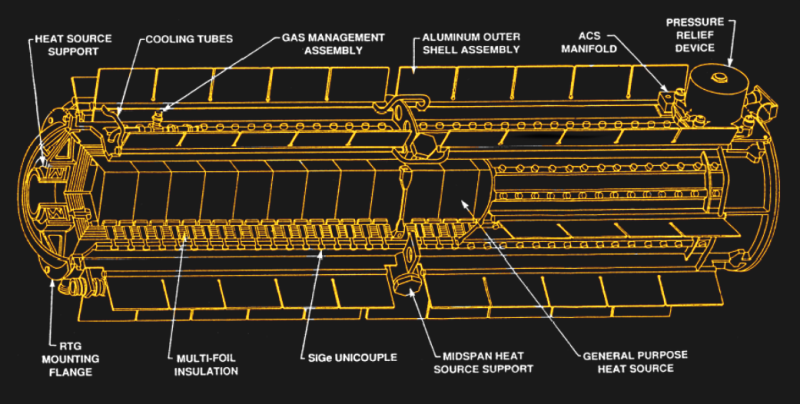

Dave says the “informal and ever expanding definition” of what makes a battery only serves to muddy the waters around the technology. As another example, the radioisotope “batteries” that power deep space probes and Mars rovers are more properly known as betavoltaics — in that they provide power not through a chemical reaction but through beta particles emitted from a radioactive source.

The Chat really covers a lot of ground, not all of it strictly related to battery technology, and makes for a fun read on a long winters night. We’d like to thank Dave Sopchak for stopping by and spurring on such a fascinating and lively discussion, closing the 2022 season of Hack Chats on a definite high note.

We’re currently putting together a slate of exciting hosts for 2023, and one of them could be you! If you’d like to be considered for a Hack Chat, simply fill out the application form and let us know what you’d like to talk about.

The Hack Chat is a weekly online chat session hosted by leading experts from all corners of the hardware hacking universe. It’s a great way for hackers connect in a fun and informal way, but if you can’t make it live, these overview posts as well as the transcripts posted to Hackaday.io make sure you don’t miss out.

““batteries” that power deep space probes and Mars rovers are more properly known as betavoltaics — in that they provide power not through a chemical reaction but through beta particles emitted from a radioactive source.”

Uh, no… There were some RTGs that used beta-emitting strontium 90 RTGs (like the Russian “lighthouse” ones, which were thermal, NOT “betavoltaic”), but those ones mentioned are all powered by PU-238, which only emits alpha particles (and some weak gamma rays), not betas (and especially not betavoltaic).

To clarify, a betavoltaic is not an RTG. An RTG is a radioisotope thermoelectric generator. You basically just take a pile of radioactive stuff and stick it next to a thermopile. Poof, electricity.

Betavoltaics generate electricity just by ionization – the high energy electron goes “splat” against the semiconductor, generating buckets of electron/hole pairs which become electricity. It’s direct radioactivity to electricity.

While we are being pedantic, it grinds my gears when people use “battery” to refer to a single cell, and “batteries” to refer to the electrochemical cells which make up their battery.

Further one can, (and quite definitely should given the opportunity), make a battery from a stack of radioactive cells.

Hooray for pedantry!! By logical extension, if a stack of any type of electrical cells makes battery, are solar panels also batteries? More importantly, is two solar panels with a battery between them a sandwich?

Actually he is correct in not calling them batteries. They are not, in any way, unless there is a plurality. They are electrochemical cells. A battery can be an array of more than a singular object of anything. Soldiers, potatoes, weapons, and yes, solar arrays. Language matters, and being pedantic about a topic such as this matters. Especially when the host was trying to be pedantic and failed when not recognizing other energy storage devices as batteries. They most certainly can be, and often are.

Also, using the term in the plural as is generally done is even worse as an array of cells would be a singular battery. Only when there is more than one battery do they become “batteries”.

> As for fuel cells powering our homes, Dave points out those units tend to run natural gas, making them unattractive considering the strong push towards renewable resources.

Which is of course ignoring the fact that “natural gas” can be manufactured without fossil sources just as well as hydrogen.

Of all the uses for fission created electricity, making natural gas from hydrogen would be a good one. Also making carbon black from thin air would be another.

Instead of making natural as and burn it for home heating it would e better to use this electricity directly.

Somebody removed the ‘nice pussy’ comment!

Or MySQL blew an index again.