The PC has had its fair share of bus slots. What started with the ISA bus has culminated, so far, in PCI Express slots, M.2 slots, and a few other mechanisms to connect devices to your computer internally. But if the 8-bit ISA card is the first bus you can remember, you are missing out. There were practically as many bus slots in computers as there were computers. Perhaps the most famous bus in early home computers was the Altair 8800’s bus, retroactively termed the S-100 bus, but that wasn’t the oldest standard.

There are more buses than we can cover in a single post, but to narrow it down, we’ll assume a bus is a standard that allows uniform cards to plug into the system in some meaningful way. A typical bus will provide power and access to the computer’s data bus, or at least to its I/O system. Some bus connectors also allow access to the computer’s memory. In a way, the term is overloaded. Not all buses are created equal. Since we are talking about old bus connectors, we’ll exclude new-fangled high speed serial buses, for the most part.

Tradeoffs

There are several trade-offs to consider when designing a bus. For example, it is tempting to provide regulated power via the bus connector. However, that also may limit the amount of power-hungry electronics you can put on a card and — even worse — on all the cards at one time. That’s why the S-100 bus, for example, provided unregulated power and expected each card to regulate it.

On the other hand, later buses, such as VME, will typically have regulated power supplies available. Switching power supplies were a big driver of this. Providing, for example, 100 W of 5 V power using a linear power supply was a headache and wasteful. With a switching power supply, you can easily and efficiently deliver regulated power on demand.

Some bus standards provide access to just the CPU’s I/O space. Others allow adding memory, and, of course, some processors only allow memory-mapped I/O. Depending on the CPU and the complexity of the bus, cards may be able to interrupt the processor or engage in direct memory access independent of the CPU.

In addition to power, there are several things that tend to differentiate traditional parallel buses. Of course, power is one of them, as well as the number of bits available for data or addresses. Many bus structures are synchronous. They operate at a fixed speed, and in general, devices need to keep up. This is simple, but it can impose tight requirements on devices.

Tight timing requirements constrain the length of bus wires. Slow devices may need to insert wait states to slow the bus, which, of course, slows it for everyone.

An asynchronous bus, on the other hand, works transactionally. A transaction sends data and waits until it is acknowledged. This is good for long wires and devices with mixed speed capability, but it may also require additional complexity.

Some buses are relatively dumb — little more than wires hanging off the processor through some drivers. Then how can many devices share these wires? Open-collector logic is simple and clever, but not very good at higher speeds. Tri-state drivers are a common solution, although the fanout limitations of the drivers can limit how many devices you can connect to the bus.

If you look at any modern bus, you’ll see these limitations have driven things to serial solutions, usually with differential signaling and sophisticated arbitration built into the bus. But that’s not our topic today.

Unibus

A common early bus was the Digital Equipment Corporation Unibus. In 1969, you needed a lot of board space to implement nearly anything, so Unibus cards were big. PDP-11 computers and some early VAX machines used Unibus as both the system bus for memory and I/O operations.

Unibus was asynchronous, so devices could go as fast as they could or as slow as they needed. There were two 36-pin edge connectors with 56 pins of signals and 16 pins for power and ground.

Unibus was advanced for its time. Many of the pins had pull-up resistors on the bus so that multiple cards could assert them by pulling them to ground. For example, INTR, the interrupt request line, would normally be high, with no cards asserting an interrupt. If any board pulls the line low, the processor will service the interrupt, subject to priority resolution that Unibus supported via bus requests and grants.

The grants daisy-chained from card to card. This means that empty slots required a “grant continuity card” that connected the grant lines to prevent breaking the daisy chain.

Eventually, the Digital machines acquired Massbus for connecting to specific disk and tape drives. It was also an asynchronous bus, but only for data. It carried 18 bits plus a parity bit. Boards like the RH11 would connect Massbus devices to the Unibus. There would be other Digital Equipment buses like TURBOChannel.

Other computer makers, of course, had their own ideas. Sun had MBus and HP 3000 and 9000 computers, which used the HP Precision Bus and HP GSC. But the real action for people like us was with the small computers.

S-100 and Other Micros

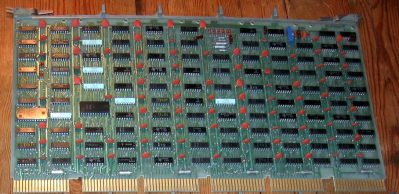

It is easy to see that when the designers defined the Altair 8800 bus, they didn’t expect it to be a standard. There was simply a 100-pin connector that accepted cards 10 inches long by 5 inches tall. The bus was just barely more than the Intel 8080 pins brought out, along with some power. At first, the bus split the databus into an input and output bus. However, later cards used a bidirectional bus to allow for more grounds on the now unused bus bits to help reduce noise.

It is easy to see that when the designers defined the Altair 8800 bus, they didn’t expect it to be a standard. There was simply a 100-pin connector that accepted cards 10 inches long by 5 inches tall. The bus was just barely more than the Intel 8080 pins brought out, along with some power. At first, the bus split the databus into an input and output bus. However, later cards used a bidirectional bus to allow for more grounds on the now unused bus bits to help reduce noise.

Through the late 1970s and early 1980s, the S-100 market was robust. Most CP/M machines using an 8080 or Z-80 had S-100 bus slots. In fact, it was popular enough that it gave birth to a real standard: IEEE 696. However, by 1994, the IBM PC had made the S-100 bus a relic, and the IEEE retired the standard.

Of course, the PC bus would go on to be dominant on x86 machines for a while; other systems had other buses. The SS-50 was sort of the S-100 for 6800 computers. The 68000 computers often used VMEbus, which was closely tied to the asynchronous bus of that CPU.

Embedded Systems

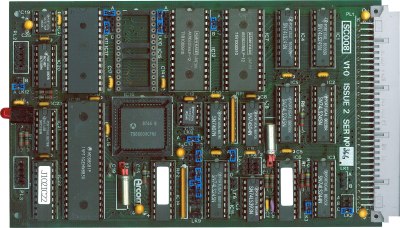

While things like S-100 were great for desktop systems, they were generally big and expensive. That led to competitors for small system use. Eurocard was a popular mechanical standard that could handle up to 96 signals. The DIN 41612 connectors had 32 pins per row, with two or three rows.

Catching the Bus

We don’t deal much with these kinds of buses in modern equipment. Modern busses tend to be high-speed serial and sophisticated. Besides, a hobby-level embedded system now probably uses a system-on-a-chip or, at least, a single board computer, with little need for an actual bus other than, perhaps, SPI, I2C, or USB for I/O expansion.

Of course, modern bus standards are the winners of wars with other standards. You can still get new S-100 boards. Sort of.

The S100 bus you say? Cannot read it without thinking about this song

https://youtu.be/bMS6G83NqFQ?si=CbadYYJEuiwXYLAt

Too much! Magic Bus!

I love it. I love it!!!

[ hearty applause here ]

Sorta wish we’d stuck with backplane-type computing

Me too. I’d love to live in the alternate timeline where Apple would actually release the Jonathan

https://512pixels.net/2024/03/apple-jonathan-modular-concept/

Now computer the wavelength of a modern interconnect bus’s frequency.

3GHz close enough…

Shortcut 1ns = 10cm for typical bus trace impedance.

How are you going to do that with a backplane?

Think that connector is going to be cheap?

Don’t see the bus that engineers get thrown under. :)

That’s usually how that works though…

If you do it right, they don’t see it coming either.

More humane that way.

VMEbus stuck around quite awhile for industrial and medical imaging. Usually using a PCI bridge card to VMEBUS.

On the SGI Octane and Origin systems the VMEBUS card cage was connected to the PCI bridge card inside the main computer with an enormous cable. While the PCI bridge card was housed in a XIO to PCI card cage. The XIO bus was one of the first high speed serial system busses.

The truncated main image looked like a set of lock-picks to me (without the interesting bits)

IBM’s MicroChannel Bus…nuff said…blech

I use to have a card that had a regular bus on one edge and the microchannel on the other. Flipped it and installed in a different machine.

S-100 had some regrettable design decisions. STD bus avoided some of the pitfalls of S-100 and the later STEbus improved on while still being fairly friendly to Z80/8080/8085 but extended to many other processor architectures perhaps more easily than S-100. (as S-100’s signaling was quite 8080-centric, minimizing the need for external logic)

Back in the 80’s and 90’s I really wished EISA (Extended Industry Standard Architecture) would have taken hold as a popular consumer-level standard. The compatibility with ISA was convenient and it was more future-proof than VLB and other local bus hacks for the PC architecture.

i was thinking transportation initially…;)

you forgot this

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zorro_II

You missed mentioning Multibus, Intel’s standard released with the MDS-800, but then used widely in industry…

What’s missing is the ECB, the Europa Card Bus.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Europe_Card_Bus

It was a connector type used over here in Europe in the CP/M and computer homebrew era.

The German c’t 86 computer used it, for example.

That was an 8086 computer that could run CP/M-86 and DOS.

(Its schematics were published in c’t magazine of the 1980s.)

Here’s an example video found on YouTube:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tujJqBYyxOc

Correction. Just noticed Euocard was mentioned, my bad. 😅

Hm.. What else was there? 🤔 The pin connector of the former East German PCs, maybe? 🙂

The EC1834 had used “ISA” cards with DIN 4162 (96pin) connectors instead of edge connectors, for example.

https://www.robotrontechnik.de/index.htm?/html/computer/ec1834.htm

I just wanted to say thank you for this article. Some of this is information I had searched for a few years back, but hadn’t found.

The Apple ][ expansion bus was a bit interesting. The form factor was a bit limiting at first, but with increasing levels of VLSI integration, the peripherals that were made for it kept on surprising me.

Well I’d be interested to know more about that card with the MC68008 in pride of place.

Up till now I’d though only Uncle Clive had used it in anything…

no mentions of zorro bus

Exactly my though. Dave Haynoe was the man of the future.

Sorry, “thought” and Dave Haynie. Phone corrections always chaos on me.

The first bus I had actual experience with, was: the HP 41C calculator.

Up to four plug in modules, for ROM, magnetic card adaptor, barcode scanner.

Enthusiasts built a custom interface, allowing cheap EPROMS to hold custom code.

The article image, cropped for the most readed/important list on top of the main page, looks like a cropped picture of a collection of lockpicks.

I waited ages for a bus, then a load came together…

Async vs. sync data transmission “you can go as fast as you want” is mixing and matching. The only difference is clocking by transition of bits, vs. a clock reference signal – both are adjustable and both can go extremely slow or fast. Nyquist theorem is also involved here to ‘sample’ whether a 1 or 0. Otherwise, solid piece on bus architectures, for those of us who were there. Perhaps a nod to the IBM S/360 bus & tag would add perspective as well.

Thanks for this article. Back in the day I was an Apple II programmer who didn’t know much about hardware. I learned a lot about how computers actually work at the logic level from a Byte Magazine article describing an S-100 memory card.

One bus nobody mentions was the “Benton Harbor Bus” featured in the Heathkit H89. The cards often had to work around the bus by using an extra umbilical cord that would plug into a RAM or ROM socket on the motherboard. One thing I still don’t understand is why the H89 cards had chirality: left-handed and right-handed versions used on either side of the CRT.