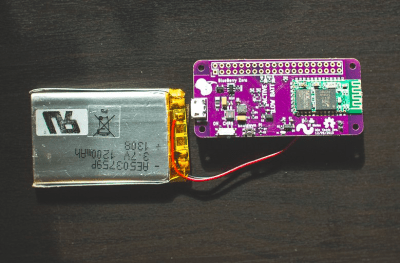

The calendar is rolling through the third week of the house that Hackaday and Adafruit built: The Raspberry Pi Zero Contest. We’re nearly at 100 entries! Each project is competing for one of 10 Raspberry Pi Zeros, and one of three $100 gift certificates to The Hackaday Store. This week on The Hacklet, we’re going to take a look at a few more contest entries.

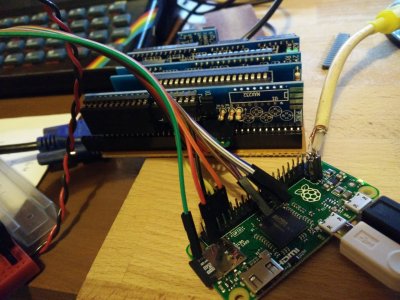

[Phil “RzR” Coval] is trying to Port Tizen to the Raspberry Pi Zero. For those not in the know, Tizen is an open source operating system for everything. Billed as a go-to OS for everything from wearables to tablets to smartphones to in-vehicle entertainment systems, Tizen is managed by the Linux Foundation and a the Tizen Association. While Tizen works on a lot of devices, the Raspberry Pi and Pi 2 are still considered “works in progress”. Folks are having trouble just getting a pre-built binary to run. [Phil] is taking the source and porting it to the limited Pi Zero platform. So far he’s gotten the Yocto-based build to run, and the system starts to boot. Unfortunately, the Pi crashes before the boot is complete. We’re hoping [Phil] keeps at it and gets Tizen up and running on the Pi Zero!

[Phil “RzR” Coval] is trying to Port Tizen to the Raspberry Pi Zero. For those not in the know, Tizen is an open source operating system for everything. Billed as a go-to OS for everything from wearables to tablets to smartphones to in-vehicle entertainment systems, Tizen is managed by the Linux Foundation and a the Tizen Association. While Tizen works on a lot of devices, the Raspberry Pi and Pi 2 are still considered “works in progress”. Folks are having trouble just getting a pre-built binary to run. [Phil] is taking the source and porting it to the limited Pi Zero platform. So far he’s gotten the Yocto-based build to run, and the system starts to boot. Unfortunately, the Pi crashes before the boot is complete. We’re hoping [Phil] keeps at it and gets Tizen up and running on the Pi Zero!

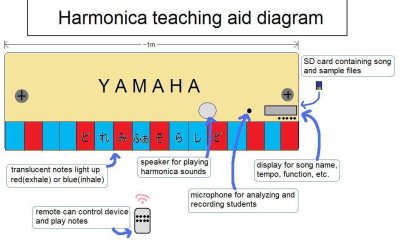

Next up is [shlonkin] with Classroom music teaching aid. Guitar Hero has taught a generation of kids to translate flashing lights to playing notes on toy instruments. [Shlonkin] is using similar ideas to teach students how to play real music on a harmonica. The Pi Zero will control a large display model of a harmonica at the front of the classroom. Each hole will light up when that note is to be played. Harmonica’s have two notes per hole. [Shlonkin] worked around this with color. Red LEDs mean blow (exhale), and Blue LEDs mean draw (inhale). The Pi Zero can do plenty more than blink LEDs and play music, so [shlonkin] plans to have the board analyze the notes played by the students. With a bit of software magic, this teaching tool can provide real-time feedback as the students play.

Next up is [shlonkin] with Classroom music teaching aid. Guitar Hero has taught a generation of kids to translate flashing lights to playing notes on toy instruments. [Shlonkin] is using similar ideas to teach students how to play real music on a harmonica. The Pi Zero will control a large display model of a harmonica at the front of the classroom. Each hole will light up when that note is to be played. Harmonica’s have two notes per hole. [Shlonkin] worked around this with color. Red LEDs mean blow (exhale), and Blue LEDs mean draw (inhale). The Pi Zero can do plenty more than blink LEDs and play music, so [shlonkin] plans to have the board analyze the notes played by the students. With a bit of software magic, this teaching tool can provide real-time feedback as the students play.

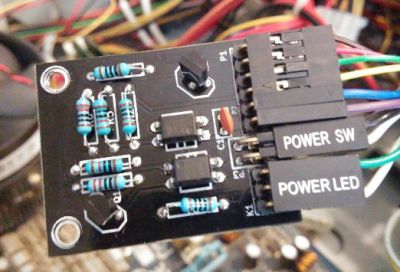

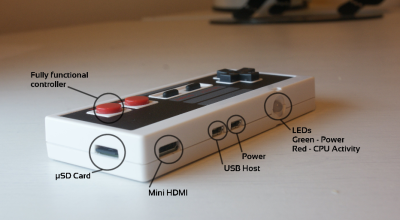

[Spencer] is putting the Pi Zero to work as a $5 Graphics Card For Homebrew Z80. The Z80 in this case is RC2014, his DIY retro computer. RC2014 was built as part of the 2014 RetroChallenge. While the computer works, it only has an RS-232 serial port for communication to the outside world. Unless you have a PC running terminal software nearby, the RC2014 isn’t very useful. [Spencer] is fixing that by using the Pi Zero as a front end for his retro battle station. The Pi handles USB keyboard input, translates to serial for the RC2014, and then displays the output via HDMI or the composite video connection. The final design fits into the RC2014 backplane through a custom PCB [Spencer] created with a little help from kicad and OSHPark.

[Spencer] is putting the Pi Zero to work as a $5 Graphics Card For Homebrew Z80. The Z80 in this case is RC2014, his DIY retro computer. RC2014 was built as part of the 2014 RetroChallenge. While the computer works, it only has an RS-232 serial port for communication to the outside world. Unless you have a PC running terminal software nearby, the RC2014 isn’t very useful. [Spencer] is fixing that by using the Pi Zero as a front end for his retro battle station. The Pi handles USB keyboard input, translates to serial for the RC2014, and then displays the output via HDMI or the composite video connection. The final design fits into the RC2014 backplane through a custom PCB [Spencer] created with a little help from kicad and OSHPark.

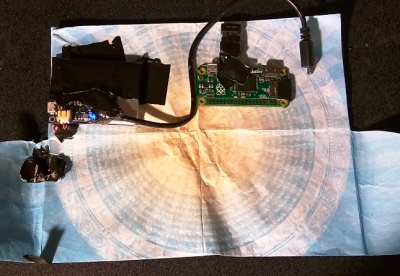

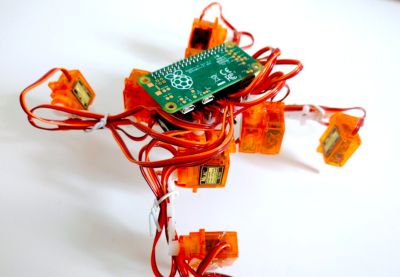

Finally we have [txdo.msk] with 8 Leaf Pi Zero Bramble. At $5 each, people are scrambling to build massively parallel supercomputers using the Raspberry Pi Zero. Sure, these aren’t practical machines, but they are a great way to learn parallel computing fundamentals. It only takes a couple of connectors to get the Pi Zero up and running. However, 8 interconnected boards quickly makes for a messy desk. [Txdo.msk] is designing a 3D printed modular case to hold each of the leaves. The leaves slip into a bramble box which keeps everything from shorting out. [Txdo.msk] has gone through several iterations already. We hope he has enough PLA stocked up to print his final design!

Finally we have [txdo.msk] with 8 Leaf Pi Zero Bramble. At $5 each, people are scrambling to build massively parallel supercomputers using the Raspberry Pi Zero. Sure, these aren’t practical machines, but they are a great way to learn parallel computing fundamentals. It only takes a couple of connectors to get the Pi Zero up and running. However, 8 interconnected boards quickly makes for a messy desk. [Txdo.msk] is designing a 3D printed modular case to hold each of the leaves. The leaves slip into a bramble box which keeps everything from shorting out. [Txdo.msk] has gone through several iterations already. We hope he has enough PLA stocked up to print his final design!

If you want to see more entrants to Hackaday and Adafruit’s Pi Zero contest, check out the submissions list! If you don’t see your project on that list, you don’t have to contact me, just submit it to the Pi Zero Contest! That’s it for this week’s Hacklet. As always, see you next week. Same hack time, same hack channel, bringing you the best of Hackaday.io!

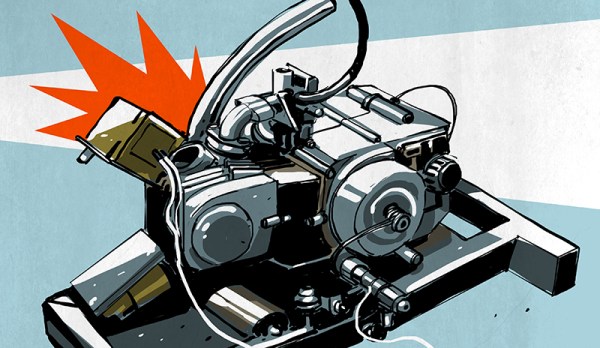

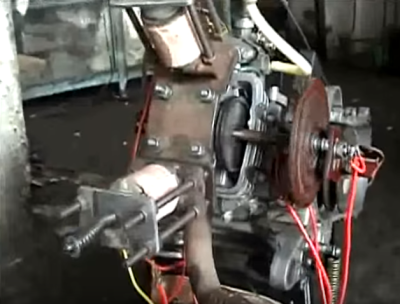

A multi-cylinder gasoline engine is a complex dance. Hundreds of parts must move in synchronicity. Valves open and close, injectors mist fuel, spark plugs fire, and pistons move up and down. All follow the four-stroke “Intake, Compression, Combustion, Exhaust”

A multi-cylinder gasoline engine is a complex dance. Hundreds of parts must move in synchronicity. Valves open and close, injectors mist fuel, spark plugs fire, and pistons move up and down. All follow the four-stroke “Intake, Compression, Combustion, Exhaust”  Engine manufacturers have spent years working around the limitations of the camshaft. The results are myriad proprietary solutions. Honda has VTEC, short for Variable Valve Timing and Lift Electronic Control. Toyota has VVT-i. BMW has VANOS, Ford has VCT. All these systems provide ways to adjust the valve action to some degree. VANOS works by allowing the camshaft to slightly rotate a few degrees relative to its normal timing, similar to moving a tooth or two on the timing chain. While these systems do work, they tend to be mechanically complex, and expensive to repair.

Engine manufacturers have spent years working around the limitations of the camshaft. The results are myriad proprietary solutions. Honda has VTEC, short for Variable Valve Timing and Lift Electronic Control. Toyota has VVT-i. BMW has VANOS, Ford has VCT. All these systems provide ways to adjust the valve action to some degree. VANOS works by allowing the camshaft to slightly rotate a few degrees relative to its normal timing, similar to moving a tooth or two on the timing chain. While these systems do work, they tend to be mechanically complex, and expensive to repair.

Simple, single-cylinder camless engines are relatively easy to build. Start with a four stroke overhead valve engine from a snowblower, scooter, or the like. Make sure the engine is a non-interference model. This means that it is physically impossible for the valves to crash into the pistons. Add a power source and some solenoids. From there it’s just a matter of creating a control system. Examples are all over the internet. [Sukhjit Singh Banga] built

Simple, single-cylinder camless engines are relatively easy to build. Start with a four stroke overhead valve engine from a snowblower, scooter, or the like. Make sure the engine is a non-interference model. This means that it is physically impossible for the valves to crash into the pistons. Add a power source and some solenoids. From there it’s just a matter of creating a control system. Examples are all over the internet. [Sukhjit Singh Banga] built

On the morning of September 26th, 2013 the city of Orlando was rocked by an explosion. Buildings shook, windows rattled, and Amtrak service on a nearby track was halted. TV stations broke in with special reports. The dispatched helicopters didn’t find fire and brimstone, but they did find a building with one wall blown out. The building was located at 47 West Jefferson Street. For most this was just another news day, but a few die-hard fans recognized the building as Creative Engineering, home to a different kind of explosion: The Rock-afire Explosion.

On the morning of September 26th, 2013 the city of Orlando was rocked by an explosion. Buildings shook, windows rattled, and Amtrak service on a nearby track was halted. TV stations broke in with special reports. The dispatched helicopters didn’t find fire and brimstone, but they did find a building with one wall blown out. The building was located at 47 West Jefferson Street. For most this was just another news day, but a few die-hard fans recognized the building as Creative Engineering, home to a different kind of explosion: The Rock-afire Explosion. Many of us have heard of the Rock-afire Explosion, the animatronic band which graced the stage of ShowBiz pizza from 1980 through 1990. For those not in the know, the band was created by the inventor of Whac-A-Mole, [Aaron Fechter], engineer, entrepreneur and owner of Creative Engineering. When ShowBiz pizza sold to Chuck E. Cheese, the Rock-afire Explosion characters were replaced with Chuck E. and friends. Creative Engineering lost its biggest customer. Once over 300 employees, the company was again reduced to just [Aaron]. He owned the building which housed the company, a 38,000 square foot shop and warehouse. Rather than sell the shop and remaining hardware, [Aaron] kept working there alone. Most of the building remained as it had in the 1980’s. Tools placed down by artisans on their last day of work remained, slowly gathering dust.

Many of us have heard of the Rock-afire Explosion, the animatronic band which graced the stage of ShowBiz pizza from 1980 through 1990. For those not in the know, the band was created by the inventor of Whac-A-Mole, [Aaron Fechter], engineer, entrepreneur and owner of Creative Engineering. When ShowBiz pizza sold to Chuck E. Cheese, the Rock-afire Explosion characters were replaced with Chuck E. and friends. Creative Engineering lost its biggest customer. Once over 300 employees, the company was again reduced to just [Aaron]. He owned the building which housed the company, a 38,000 square foot shop and warehouse. Rather than sell the shop and remaining hardware, [Aaron] kept working there alone. Most of the building remained as it had in the 1980’s. Tools placed down by artisans on their last day of work remained, slowly gathering dust.