Majenta Strongheart takes a look at a couple of cool entries from the first round of the 2018 Hackaday Prize:

This is an infinite 3D printer. The Workhorse 3D is the way we’re going to democratize 3D printing. The Workhorse 3D printer does this by adding a conveyor belt to the bed of a 3D printer, allowing for rapid manufacturing, not just prototyping. [Swaleh Owais] created the Workhorse 3D printer to automatically start a print, manufacture an object, then remove that print from the print bed just to start the cycle all over again.

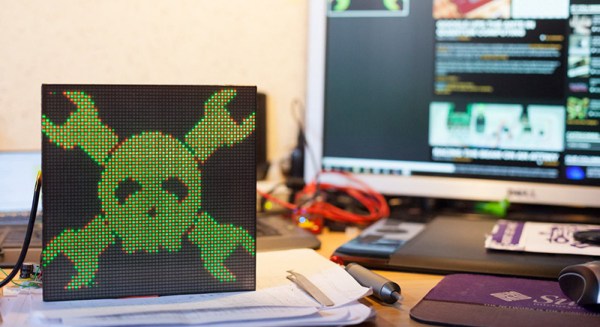

Check out this Numitron Hexadecimal Display Module from [Yann Guidon]. [Yann] is building an entire computer, from scratch, and he needs a way to display the status of various bits on a bus. The simplest way to do this is with a few buffer chips and some LEDs, but that’s far too easy for [Yann]. He decided to use Numitron tubes to count bits on a bus, from 0 to F. Instead of microcontrollers, he’s using relays and diode steering to turn those segments of the Numitron on and off.

Browse all of the entries here. Right now, we’re in the Robotics Module Challenge part of the Hackaday Prize, where twenty incredible projects will win one thousand dollars and move on to the final part of the Hackaday Prize where one lucky winner will win fifty thousand dollars for building awesome hardware. If that’s not incredible, I don’t know what is.

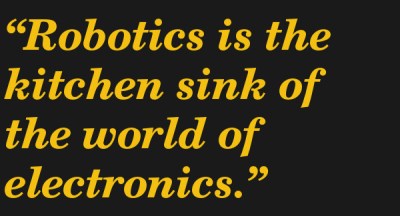

Robotics is the kitchen sink of the world of electronics. You have to deal with motors, sensors, spinny lidar doohickies, computer vision, mechatronics, and unexpected prototyping issues accounting for the coefficient of friction of 3D printed parts. Robotics is where you show your skills, and this is your chance to show the world what you’ve got.

Robotics is the kitchen sink of the world of electronics. You have to deal with motors, sensors, spinny lidar doohickies, computer vision, mechatronics, and unexpected prototyping issues accounting for the coefficient of friction of 3D printed parts. Robotics is where you show your skills, and this is your chance to show the world what you’ve got.